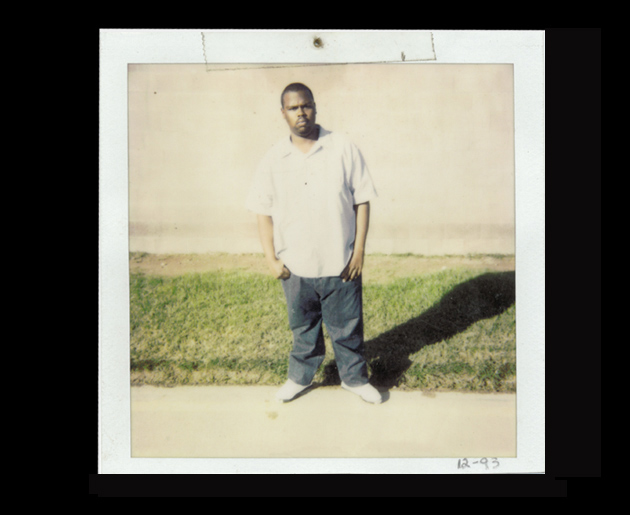

"Fat Tone" at California's Calipatria prison, December 1993.Courtesy The Atavist

The following is an adapted excerpt from Stray Bullet, Gary Rivlin’s new Atavist single.

Five months after his wedding ceremony—conducted through the Plexiglas partition of a prison visiting room—Tony Davis was finally ready to face his parole board. He would be judged by two officials from a stable of roving commissioners. There would be a deputy prosecutor representing the people of Alameda County, and, in Tony’s corner, a state-provided defense lawyer. But the most crucial advocate would be Tony himself, head shaved, dressed in prison blues, and wearing his government-issue steel-framed glasses.

Gone was the lingering dread that had plagued him since his first parole hearing, the one he’d botched so badly 10 years before. Three years had passed since his last serious write-up. He was a married man now and right with God—a reformed sinner.

The argument for keeping Tony locked up could be made in one sentence: He killed a boy. He would claim that he had meant only to scare the kids when he fired a .45 five times from the back of a moving car. But it was the misfortune of 13-year-old Kevin Reed that one of the bullets had ricocheted off the pavement and perforated his groin—he bled to death by the time the ambulance arrived. Tony’s impulsive act sent two other children, both 14, to the hospital with gunshot wounds. Listen to this snippet from his confession:

That was Tony at 19, nine months after the shooting. The Tony Davis who would face the parole board in 2012 was nothing like the messed up teen whose mother was on heroin before she turned to crack, whose father he’d met only a few times. Nothing like the oversized, sad-faced kid raised by a grandmother who was already exhausted from raising eight of her own, as well as a pair of Tony’s younger siblings. Nothing like the kid whose teachers stuck him in remedial classes at age 10, and who, at age 13, was set up in the crack trade by an adult neighbor and a pair of slightly older uncles. Nothing like the boy who called himself “Fat Tone” and ran his own corner crew.

The episode that led to Tony’s incarceration began one summer day in 1990, when Kevin Reed’s brother Shannon and his friend London, both 14, mistook “Junebug,” a kid from Tony’s crew, for a boy who had threatened to beat them up earlier that week. They jumped him, and stole his bike for good measure.

The next night, Junebug and his friend Aaron went looking for payback. After spotting London and a kid they thought was Shannon—it was Kevin—they fetched Fat Tone, who had been drinking and smoking pot all day. Tony grabbed his gun and slipped into the backseat of Aaron’s car. “I ain’t fit to kill nobody,” he remembers telling the others after the shooting. And maybe he wasn’t. But now he had.

Nine months later, the police finally tracked the boys down. Tony ended up confessing. Allowed his one phone call, he called his grandmother’s house. Listen:

I first met tony davis in the early 1990s, when I was a young reporter for an Oakland-based alternative weekly. The city was a hot spot in the nation’s crack epidemic, and turf warfare had sent its homicide rate soaring. I wanted to put a human face on the issue of teens killing teens, which is how I met Tony, who was two years into an 18-to-life sentence for Kevin Reed’s murder. That shooting would become the focus of my 1995 book, Drive-By.

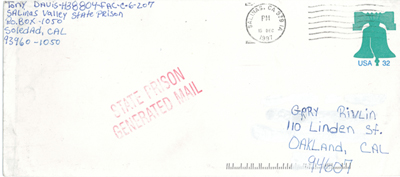

We kept in touch, and somewhere along the way, Tony ceased to be my subject and became my friend. Over the years, we have exchanged probably a couple hundred letters and shared countless phone calls. Inmates sometimes ask him about the white man whose picture is on his cell wall. “He’s like the only real best friend that I’ve had in years,” Tony tells them.

To describe Tony as remorseful doesn’t begin to capture it. For years, I couldn’t talk to him without him somehow bringing up the night of the murder. At one point he referred to it as an “incident,” and then quickly corrected himself. “The night I killed that young man,” he said, more carefully. “I killed a boy. I know that. Kevin Reed. I’m not going to try and hide it by calling it an ‘incident,’ because it was a murder and someone—Kevin—lost his life.”

I was raised on Long Island in a stable middle-class family, and yet it was easy for me to put myself in Tony’s shoes. My older brother took bets on pro football games in high school, and so I got into the business as well. What if the cooler, older kids in my neighborhood had been selling crack instead? “Prison is not easy,” Tony told me a few years back. “It’s not like we sitting in here looking at cable, getting fed the best food in the world. It’s misery. It’s a horrible experience. And anyone who says you sit around on your rear end and have it light is lying.”

Our friendship advanced one conversation at a time. Tony would call, and I would drop whatever I was doing and accept the charges.

One of his calls, about a year after the publication of Drive-By, came at a particularly crazy time. My wife’s mother had recently passed away, and I was behind on everything. But rather than rush him off the phone, I found myself talking about my late mother-in-law, who had strangely been drawn to Tony’s plight.

She was the type of person, I told Tony, who up until a few years earlier would have advocated 2,000 volts for the likes of him. But that changed the day she overheard me transcribing one of our conversations. She began asking after Tony, and at one point even offered to contribute to a Christmas care package for him.

The subject of my mother-in-law’s passing got Tony talking about his own mother. The last I had heard, she was back in jail, but now she was out and enrolled in a drug-treatment program. My inner cynic told me she probably just got arrested again and took treatment to avoid jail time—she had done this before. But Tony couldn’t have been happier. “My mother and I have always been close, even though she was never there for me,” he said. “I mean, she did a lot of messed up things. But out of all the people in my family, she was the only one that really understood me.”

Tony liked to gripe, but he also was a good listener. I was never reluctant to share bad news with him. I figured even a bad day on the outside was better than a good day in prison, and I was glad to remind him that even greener pastures have ruts.

In one call, not long after the September 11 attacks, I’d been expecting a forlorn phone companion. He must have written me one of his down letters, because I started off, “You feelin’ better than you were when you wrote that note?”

“You know how it goes,” he said.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean you know we all have our up days and our down days. You’re actually calling me in a…”

“Exactly.”

“I’ve had a down few weeks,” I admitted. At the time, I was living off freelance magazine work. Things had been going great—until the attacks.

“Everything has dried up after September 11,” I told Tony. “Like I don’t write about the stuff that people want to hear about right now.”

“Yeah.”

“So suddenly I’m having a hard time getting work.”

“Yeah, I understand.”

Later in that conversation, Tony talked about how the attacks were received by his fellow prisoners. Around half the inmates were like him, he said: angry that America had been attacked. But the other half were happy the twin towers had fallen.

“Happy?”

“I’m just trying to be honest with you.”

By this point in my career, I had switched over to writing mainly about technology, and was on the move a lot thanks to changing life circumstances and the boom-and-bust economy. Even so, I managed to stay connected with Tony, whose world remained no wider than the five cellblocks that prison designers had arranged in a ring to create a secure gated community.

He could call at the most inconvenient times—often I would be on the phone with an editor or in the middle of interviewing some tech executive. But I took his calls even when it meant having to explain myself after the fact. It always made for an interesting conversation once I got those people back on the line. Invariably, the men would bring up prison rape. (Tony thinks popular culture greatly exaggerates the extent of rape in prison, and that most prison sex is consensual.) Then I would need to steer the conversation back to the topic at hand—the future of social networking, say, or the state of venture investing.

There was something gratifying in watching him “mature up,” as Tony called it. “I’m trying to learn that I don’t have to always be using my hands, because I can use my mind,” he said early on. “It used to be like I used my hands if I wanted to get someone’s attention, but now I’m trying to use my mind and my mouth.” Sure, I was watching friends trying to impart the same lesson to their toddlers, but so what? If anything, it was more impressive to watch Tony come to this realization on his own.

“When I was on the streets, I was mentally dead,” he told me during a reflective moment. “I didn’t know anything about nothing. When I came to prison, I started reading and looking and learning and seeing, and started understanding what the world was about. It took me a long time to really embrace that. Because I still wanted to just be angry, negative, and blame everybody.”

In January 2008, the two of us got to talking about the presidential race. Obama had just won the Iowa caucus, and I was wondering if the results had changed his mind. Tony had previously declared himself a Hillary man because, he said, he admired her steely toughness. He was wavering now, but still not ready to jump sides.

“Really?” I asked him. “You wouldn’t vote for Obama?”

“I haven’t really decided yet.”

I was incredulous. “You’re a young black man. Here’s an impressive black man who can become president.”

“I would vote for Barack,” he said, “but the thing that really’s got me hesitating is his lack of experience.”

The more he talked, the more clear it was to me that he was paying as much attention to the election as I was—even though, as a convicted felon serving time in California, he was barred from voting. He’d read both of Obama’s books and faithfully perused hand-me-down USA Todays borrowed from an inmate with a subscription.

And that’s when I interrupted the flow of our conversation and—this is the problem with taping yourself—said something stupid. I asked him whether he watched the presidential debates in a prison common area or alone—in his “room.”

I tried to laugh off my faux pas, but Tony wasn’t about to let me slide. “Hell, no,” he said. “I will never get comfortable to the point I call my cell my room.” Later during that same conversation, he noted that he’d been in prison just about as long as he’d lived on the outside: “I’ll be 37 in August. I can’t dwell on what happened, how I got here, or how long I’ve been here. I can’t be mad, because being mad ain’t going to help.”

In early 2010, Tony started talking about his next parole hearing, scheduled for 2012. If only he could persuade the parole board that he was a new man, he’d be free, assuming the governor didn’t reverse the decision.

Even the men and women who had watched Tony pass through the system on his way to prison had detected something different about him. The 250-pound boy with the flat top just seemed out of place. A county probation officer put this in her report: “We want to add that this case seems particularly tragic and that this defendant appears, by hindsight, to truly understand his mistakes and poor judgment.” It was doubtful, she wrote, that it would take even 10 years to rehabilitate Tony.

Al Hymer, Tony’s public defender, had handled hundreds of murders. Tony stood out because he only wanted to talk about the terrible thing he had done, not what Hymer could do to lessen his punishment. When Hymer wanted to challenge the admissibility of Tony’s confession, Tony told him not to bother. He was so remorseful that he took a deal that had him pleading guilty to second-degree murder, even though it meant an indefinite life sentence.

With time, Tony would regret that decision, given the slim odds that he would win parole. All around him, lifers had given up all hope of gaining their release and it was no wonder. Of the roughly 6,000 lifers appearing before the parole board each year, only about 6 percent are approved. But fewer than 1 percent are actually released, because the governor, since 1988, has had the power to overturn the board’s decisions. Arnold Schwarzenegger reversed about 75 percent of the paroles granted during his two terms. Gray Davis, his predecessor, reversed 99 percent.

What’s more, Tony had found it all but impossible to pursue the self-improvements the parole board wanted to see. Between lockdowns and teacher turnover, his GED classes were canceled for 8 of his first 12 months at one prison; at another, classes were often suspended due to warring gangs and teachers who would resign and not be replaced for months. “My soul is dead,” he wrote after one long stretch of lockdowns. “I been curse since birth…I’m in hell Gary I relly am.”

He would declare 2005—the year he turned 34—the worst of his life, and 2006 wasn’t looking much better. “To relly be honest,” Tony wrote me that April, “I wish at times they would have kill me instead of letting me go through this misery.”

But fate intervened. With good behavior, Tony was deemed eligible for a transfer to Solano, a medium-security prison near San Francisco. It was still prison. His new cell was no larger than the maximum-security ones, and the guards were still plenty mean. “It’s like a lot of them come to work every day basically so they can act like bullies,” he says. “They have this one lady who works in our building. She’s the most miserable—I have never in my life hated someone like I hate her. Hate is a messed up word to use. But this lady, it’s like she goes out of her way to mess with people.”

Even so, Solano meant far less violence and a lot more freedom of movement. Tony enrolled in an intensive psychotherapy regimen and a 12-step program. He grew more serious about religion and finally, at age 36, earned his GED—”Davis has worked exceptionally hard to improve himself,” one of his instructors wrote. Several years later, he’s only a few credits shy of an associate degree. It was at Solano that a fellow inmate introduced him to a woman named Candace, a devout Christian who had three daughters and ran a day care center out of her home. “I sensed right away that he had a good heart,” she later told me.

Tony would need all the support he could get in 2010, when a guard caught him talking on a cellphone—a serious violation. When Tony told me about it, my heart sank: I was, in a small way, complicit. I knew about the phone. It made our conversations easier. And I have to admit that I had turned off the critical part of my brain that would have asked the obvious: How was Tony able to afford it?

The answer was more bad news. Tony, it emerged, had been busted not only for the phone, but also for drug possession. He wasn’t using or selling, he insisted, but merely stashing extra product for a dealer he knew. His punishment was 12 months in the hole and a three-year ban on contact visits. More critically, he would have to explain the whole thing to a parole board.

When Tony first started talking about his 2012 parole hearing, he would alternate between anticipation and dread. After nearly 20 years in prison, even the crime for which he was incarcerated seemed like an anachronism: Crack has fallen out of fashion, drive-by shootings are far less common, and the national youth homicide rate is half what it was. Tony committed his crime as a teenager. Now he was 40. Wasn’t it time to give him a second chance?

Brian Thiem, the homicide cop who had arrested Tony, thought so. When I tracked him down last year, he pointed out that Tony’s crime was “an unfortunate accident based on the impulses and action of kids.” He then added, “Twenty years for what he did? God, I say let him out.”

For once, politics seemed to be working in Tony’s favor. In the spring of 2011, the Supreme Court deemed California’s prisons unconstitutionally overcrowded and ordered the state to release more than 30,000 inmates—about one-fifth—by 2014. To me, Tony seemed like the perfect candidate, especially with the state slashing billions of dollars to tame its deficit, yet spending $47,000 per inmate each year. For the first time since his incarceration, I felt excited about his prospects.

“The thing that really hit me is that there’s a lot of guys in here that’s worse off than I am,” Tony told me a few years back. These men came from abysmal beginnings, he said, but now they were among the gentlest, most morally sound individuals he knew. And that gave him hope.

“You just have to have faith and stay strong,” he went on, “and not let the situation get you so bitter to where you give up.”

Read more: Will the parole board give Tony a break? To find out, download Gary Rivlin’s Stray Bullet from The Atavist.