Babies without lots of clean diapers are at risk of child abuse<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=2mA2ouT9GDBhs43jHLv7Xg&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=diaper+change&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=3451285&src=Fl8JEOMVlcvNFFOvv9zwng-1-44">GVictoria</a>/Shutterstock

Being poor and trying to raise children is stressful on a host of levels, but it’s especially tough for people who can’t afford diapers. New research from Yale University’s school of medicine finds that depressed, low-income mothers might need Pampers far more than they need Prozac. The study found that women who lack an adequate supply of diapers for their babies are more likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety than other low-income mothers. Maternal depression and mental health problems, the researchers say, can have longterm and debilitating effects on children’s well-being and their performance in school.

The researchers, who have been studying mothers in a Connecticut low-income housing project, found that the lack of an adequate supply of diapers was a better predictor of a mother’s mental health need than even food insecurity. The average baby needs between eight and 10 diapers a day, at a cost of around $120 a month, according to the DC Diaper Bank, a nonprofit that provides free diapers to poor families in DC. But Yale researchers found women who were trying to stretch a single diaper for an entire day, thanks in part to their lack of cash and the high price of the products in their neighborhoods. Not only does a diaper shortage lead to mental health problems in the mother, it’s also been directly linked to child abuse. After all, a wet, smelly baby is a very unhappy baby, and one likely to have a raging case of diaper rash to boot.

In a way, the study seems like a no-brainer: Of course not being able to buy diapers is stressful! But the study has special relevance for American poverty policy. Since 1994, when the nation ended welfare as we know it, the safety net has become increasingly organized around food stamps, not cash grants, for poor mothers. You can’t buy diapers with food stamps.

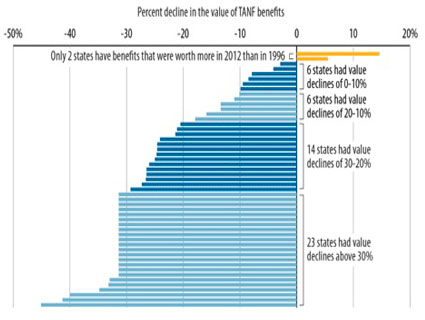

Very few low-income families are able to get cold hard cash from government safety net programs, as they did before welfare was “reformed.” Today, only about 4 million Americans receive benefits from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF), compared with 14 million in 1996, even though the poverty rate is higher today than it was back then. According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, of every 100 families with children in poverty today, only 27 receive any form of TANF benefits, compared with 68 in 1996. Those who do get some cash are getting far less of it, as the monthly benefits—never large to begin with—have fallen as much as 30 percent since welfare reform began. In 14 states, a family of three receives less than $300 a month.

Not surprisingly, the program no longer lifts many kids out of deep poverty (defined as living at below 50 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $9700 per year for a family of three). In 1995, the program kept 2.2 million kids out of deep poverty, about 62 percent of the kids at risk of those dire circumstances. By 2005, that number had fallen to about 650,000—just 21 percent of the children at risk for deep poverty.

All those figures mean that far fewer poor moms can afford diapers, and that one factor is now linked to a significant and also avoidable problem with long-term implications for the nation’s poor children. The irony, too, is that by changing federal policy to make it impossible for poor women to buy the critical things they need to care for their babies, policymakers have also inadvertently made it difficult for poor women to go to work or receive work training, one of the key goals of the ’94 welfare overhaul. That’s because child care providers won’t take poor women’s children if they can’t provide an adequate supply of diapers.

In the wake of welfare reform, nonprofits like the DC Diaper Bank have sprung up to try to distribute free diapers through neighborhood service organizations and other programs that serve low-income moms. It’s not nearly as effective as having a better national poverty policy, but a good idea nonetheless. You can find a local one and ways to donate here.