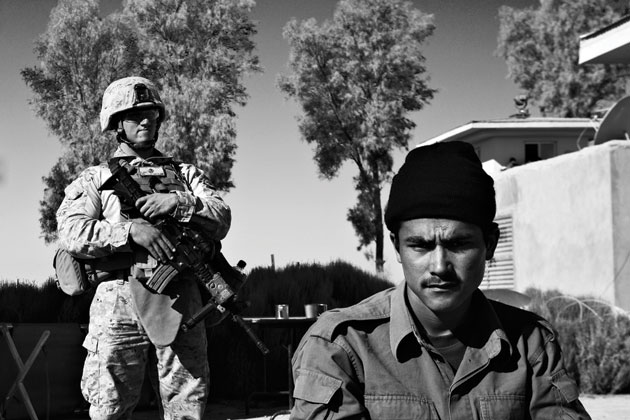

Outside the Garmsir police station, where an Afghan cop opened fire on unarmed Marines in August 2012Photograph by Sebastiano Tomada Piccolomini

August 10, 2012, was the 22nd day of Ramadan, the holy month when devout Muslims fast from dawn until dusk. Summer days in southern Afghanistan are long and brutally hot, and the few dozen officers at the Garmsir headquarters of the Afghan National Police were relieved when, as the light slanted low over the Helmand River, the sunset call to prayer finally sounded. After the evening meal, no one paid much attention as Aynuddin, the 17-year-old assistant to the police chief, walked into the station, picked up an AK-47, and headed toward the open-air gym out back.

There were seven Marines in the gym that night, part of a police-training team that lived on the second floor of the dun-colored police station. They liked to use the gym—a makeshift cluster of weights and equipment under camouflage netting in a corner of the yard—after dusk, when the heat had begun to dissipate. Hospital corpsman David Oliver, a buff, blond, 24-year-old medic, was skipping rope in the corner. Two younger Marines, Greg “Buck” Buckley Jr. and Richard “Richie” Rivera, were doing dumbbell curls, yelling “Beach Day!” each time they brought the weights to their shoulders.

Members of the close-knit group had fantasized about Beach Day since the unit landed in Garmsir four months earlier. Once they arrived back at their base in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, this long-awaited day would be dedicated to women, waves, and booze, the things they missed most in dusty Afghanistan. They had planned every moment—where they’d stay, who’d carry the cooler and who the boom box. In just 40 hours they would begin the journey home. That’s why 29-year-old Staff Sgt. Scott Dickinson had joined them. He was trying to get in better shape for his wife.

The end of the deployment couldn’t come soon enough. Garmsir wasn’t exactly the action-packed war zone that they had been hoping for. Southern Helmand was largely peaceful now, three years after the 30,000-troop surge ordered by President Obama began in earnest, and none of them had fired a single shot in battle. Mentoring the Garmsir police force was a thankless task that they had come to loathe. It wasn’t just that the Afghan police were shockingly ill-trained and corrupt, or that the Marines spent their days teaching them the most rudimentary of tasks, such as using handcuffs or tourniquets. What was really galling was that the police clearly didn’t want them there. “The Afghans didn’t really give a shit,” Oliver recalled. “We’re supposed to be helping them, and it’s hard for us to understand that these guys really do not want our help.”

Lurking behind the resentment was a gnawing concern: that one of the cops might turn on the Marines without warning. So-called green-on-blue (or insider) attacks had been sweeping Afghanistan, leaving dozens of Americans dead. Innocent frictions between the two sides in Garmsir—such as arguments over living space—now took on a more menacing tone. The Marines felt like they were walking on eggshells. “I didn’t ever feel safe,” Oliver said. “It was, ‘Be aware, never trust them, always have your weapon on you.'” But that evening he and some of the other Marines had left their pistols on the weight rack. They were almost home free.

Aynuddin stepped into the gym and leveled his rifle.

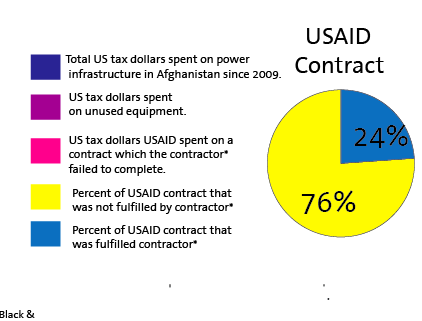

The surge of insider attacks came out of nowhere. In 2007 and 2008, there were just six such attacks combined against members of the US-led International Security Assistance Force. The following year there were 8, the next, 15. In 2011, there were 22 attacks that killed 33 ISAF soldiers and wounded 50. In 2012, the number of attacks more than doubled, with 48 incidents that killed 64 soldiers, accounting for 16 percent of all coalition combat deaths that year. “The sudden wave of insider attacks caught NATO and the Obama administration completely by surprise,” says Graeme Smith, a Kabul-based analyst at the International Crisis Group. “It cut against the grain of counterinsurgency theory, because these betrayals happened right at the moment when the internationals were lavishing money and attention on the Afghan forces.”

The attacks have had a dramatic psychological and political impact on the international mission in Afghanistan. An attack that killed four soldiers in January 2012 convinced French forces to pull out of Afghanistan by the end of the year. “The French army is not in Afghanistan so that Afghan soldiers can shoot at them,” then-President Nicolas Sarkozy said.

The perpetrators have come from each of Afghanistan’s regions and major ethnic groups, and from every branch of service. They range from lowly recruits to colonels, from teenagers to men in their 60s. Some have been identified as Taliban infiltrators, and many of the surviving attackers have cited their anger at the occupation of their country. But the US military maintains that the majority of attacks have no relationship with the insurgency, and are the result of what it calls cultural conflicts—like the February 2012 case of an Afghan soldier who shot two US troops at Bagram Airfield over the accidental burning of Korans by NATO soldiers.

The attacks have confounded military leaders. There was no parallel experience in Iraq or Vietnam, where the United States also battled powerful insurgencies while simultaneously training local forces. Nor does the cultural hypothesis fully explain why insider attacks exploded in the last two years, after thousands of coalition soldiers have been in Afghanistan for nearly a decade and the bulk of the surge troops were in place by the summer of 2010.

By 2012, the attacks had precipitated a crisis in ISAF’s training and transition plan. The Obama administration’s withdrawal strategy hinges on training a functioning Afghan army and police force that will fill the void once all US combat troops exit Afghanistan in a little more than a year. The training mission had to go forward for the strategy to have a glimmer of success. But soldiers were dying in alarming numbers at the hands of their Afghan allies. This is what the ISAF command was grappling with in the spring of 2012, when the helicopters carrying Buck and his unit touched down in Garmsir.

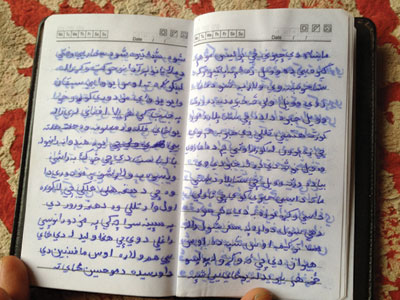

Once upon a time there was a boy who was seventeen. He would always go to school and attend his classes, but at home he would constantly get into fights, and his brothers and his family were very unhappy with him.

One day, he got into an argument with his mother. She would normally curse him, but this time she even said, “I hope you are hit by a cold bullet.”

So she wished even death for her own son. This sentence made him very sad. By now it was sunset, and the boy took some money that he had and left the house.

“It all started over an argument. I don’t know if the Taliban had any influence.” ANP Jahanzeb Baloch, 22.

Lashkar Gah, about an hour and a half drive north along the river from Garmsir, is the quiet provincial capital of Helmand, where bazaars selling pomegranates and freshly slaughtered chickens bustle for an hour at sunset before plunging into a deep nocturnal calm. I had come here with a question whose answer had eluded both the Marines and the Afghan government after the Garmsir attack that had killed three Marines: Why had Aynuddin committed such a brutal act?

His family wasn’t hard to find. They lived down a side street and invited me into their modest, concrete-walled guest room, a common feature of many Afghan homes. I sat down cross-legged with the men of Aynuddin’s family, glasses of green tea steaming before us in the brisk winter air. His 27-year-old half brother, Isamuddin, sat across from me and did most of the talking. He was a truck driver, and he had a round face with black eyebrows that pointed upward in the middle like chevrons, giving him an air of constant concern. Beside him was Shamshad, Aynuddin’s full brother, 16 years old with pale freckles, clear green eyes, and roughly chapped hands. “He looks exactly like his brother,” Isamuddin said, patting him on the shoulder.

The brothers had grown up during the civil war, a brutal conflict during which many Afghans perished from hunger and lack of medical care. Life was better now, though. Isamuddin and relatives had a decent business hauling containers to the military bases, and so the younger boys like Aynuddin and Shamshad had a chance to go to school. “We grew up illiterate and uneducated,” Isamuddin said, tapping his head, “and it’s only today that we know about education.”

Like many of his peers, Aynuddin had started school late and had only reached eighth grade by the time he was 17. Still, he was, his brothers said, the brightest and most diligent student in the family, spending hours on his homework and taking private English lessons in the afternoons. Then, in late 2011, a motorcycle wreck left him unconscious in the hospital for several days. He recovered, but after the accident his behavior changed. He was less interested in his studies and got into violent fights with his brothers and mother, throwing punches and smashing dishes. One day, following a particularly heated dispute with his mother, he ran away from home and ended up joining the police.

I asked his brothers why they thought Aynuddin had turned his gun on the Marines. Was it possible that he had been recruited by the Taliban? They emphatically denied it. “Our family doesn’t have any links with the Taliban,” Isamuddin said. He thought perhaps Aynuddin’s head injury and temper had led to the incident. Or maybe the Marines had abused or insulted him somehow. Aynuddin’s mother, who had been listening to our conversation outside the door, began weeping loudly. Shamshad, and then Isamuddin, teared up as well. “She regrets getting into the argument with him,” he said softly.

Aynuddin was a sensitive type, he explained, always reading and writing. When I asked what he wrote, Isamuddin told Shamshad to fetch “Aynuddin’s book.” The boy returned with a small day planner with a fake leather cover, its first dozen pages covered in tidy Pashto script. It was a story Aynuddin had written about running away from home. I was astonished. Diary-keeping is an exceedingly rare habit in rural Helmand, and the language is surprisingly articulate for a boy with minimal schooling.

As night fell, the boy went to the park to sleep. Around midnight, a pack of dogs came into the park and surrounded him. He drew his shawl tight and rolled himself inside of it. The dogs came and sniffed at him, but finally the night passed. In the morning, he was hungry, and wondered what to do.

He was tired, thirsty, and hungry. He had run away from home and was now ashamed in front of the entire world. He couldn’t even ask for bread, he was too embarrassed. Filled with regret, he asked himself, why did I do this?

The week before Christmas, Greg Buckley Sr. pulled his moving van onto a New York City street teeming with holiday shoppers. On each of the van’s rear windows was a poster with a photo of a young Marine in his tall, white dress hat, a kid with olive skin and soft, handsome features. “Greg Buckley Jr.,” the posters read. “21 Years Old From Oceanside, NY. Never Forget.”

Buckley got out and fed the meter. He isn’t tall, but there’s a solidity to his frame, and he stabbed a callused palm at me in a handshake. We walked into a burger joint and sat down at a table with a red-and-white-checkered cloth. There were plastic wreaths on the door, and a techno version of “Jingle Bells” played on the radio. It would be the family’s first Christmas without Greg Jr.

Buckley has a blunt forehead and deep-set blue eyes; he talks with a Long Island swagger where profanities seem a natural part of speech, especially when he’s angry. Buckley feels his son’s death could have been avoided if the Marines had taken more precautions and hadn’t been living among the police; he says that’s why the Marines haven’t responded to his repeated requests for a copy of the investigation into Greg Jr.’s death. (According to a spokesman, the Marine Corps gave Buckley a preliminary report, but it has not received a copy of the full inquiry, which was conducted by Navy investigators.)

Buckley never wanted his oldest son to join the Marines—he hoped he’d someday work for the family appliance delivery business. The family lived in Oceanside, a well-off Long Island suburb of two-car garages and wide lawns whose social life revolves around the school, sports field, and shopping mall. Greg Jr. was nine when the September 11 attacks happened, and afterward he started talking about joining the Marines. His father never took it seriously. Then one evening in 2009, during Greg Jr.’s senior year in high school, Buckley came home to find a recruiter sitting in his kitchen. “Your son wants to join the Marine Corps, sir,” the sergeant told him.

“Do me a favor, no disrespect, but pick up all your shit and get the fuck out of my house,” Buckley replied, furious that the man had come into his home without his permission.

But Greg Jr. wasn’t going to be a child for much longer. He turned 18 that summer and, with his father’s reluctant blessing, joined the Marines. The deal they struck was that he would stick with some safe and useful trade, serve his country for a few years, and then come home to Oceanside.

After boot camp, Greg Jr.—Buck to his Marine friends—was sent to Kaneohe Bay to work in a warehouse for a supply and logistics unit. It was a shock to have his son so far away, but Buckley’s doubts were somewhat assuaged when he flew out to Hawaii to visit his son and found that he was growing into a man, confident and respectful. Then, in early 2012, Greg Jr. informed his dad that he was being deployed to Afghanistan. Buckley was devastated—he thought his son’s enlistment contract precluded combat tours—but there was nothing he could do. Buckley assumed Greg Jr. had been ordered to go. The truth was, his son had volunteered when space opened up on a Police Advisor Team, or PAT. His best friend Richie Rivera was going, and Buck didn’t want to miss out.

After finishing their training, the PAT arrived in Garmsir in April 2012 for a six-month rotation. They had barely moved in to the police headquarters when a new wave of insider attacks began.

Understanding why the sudden spike of insider attacks began in 2011—well after the peak of the surge had passed—requires revisiting the compromise made by the Obama administration two years earlier, when it bowed to the requests of American generals, including David Petraeus, for more troops to support their ambitious counterinsurgency campaign. The administration’s caveat was that the surge forces had to be out by 2011, and that all combat operations had to cease by the end of 2014, with only an unde?ned training and advisory mission to continue thereafter.

Once the surge troops had beaten back the resurgent Taliban, the second half of the strategy called for ISAF forces to train their Afghan counterparts to take their place, allowing the United States and its allies to pull back from an increasingly costly and unpopular war. Given the timeline, that meant going big quickly—the size of the Afghan security forces would have to more than double in just a few years, increasing from 150,000 at the start of 2009 to 350,000 by the end of 2012—in a country whose institutions have been destroyed by decades of war, and where the attrition rate was so high that a third of the entire Afghan army had to be replaced every year. At the peak of this recruiting frenzy, the Afghan military and police were signing up 15,000 men per month. Virtually anyone was accepted, no questions asked, and units were often headed by officers who had paid bribes for their positions.

Embedding special-forces trainers with local units has long been a basic part of counterinsurgency doctrine, but this was different. The short time frame and huge ambitions of the Obama administration’s strategy called for close-contact “partnering”—not just involving experienced trainers, but other troops as well—on a scale never seen in Iraq or Vietnam. ISAF’s motto became “shona be shona” (“shoulder to shoulder” in Dari), and the bulk of ISAF combat troops were ordered to live cheek-by-jowl with Afghan forces, so the local recruits would learn by example. To keep up with the pace of recruitment, ISAF training teams were padded with enlisted men who specialized in maintenance and logistics—tasking inexperienced Americans with training inexperienced Afghans.

Buck’s PAT, for instance, was composed of a hodgepodge of volunteers from different units, thrown together to meet the sudden demand for trainers. Some were military police, but others were supply clerks and forklift drivers. “They were like, ‘Hey, who wants to go to Afghanistan?'” said Oliver, the team’s medic.

The whole partnering exercise was a combustible recipe for cultural clashes. Beneath the rhetoric of cooperation, the assumption that armed Afghan and American 18-year-olds would benefit from each other’s company was wildly optimistic. Among smaller units in areas of heavy fighting, where Afghans and US soldiers relied on each other daily to stay alive, the bonds of combat tended to dissolve these differences, but tensions flared on midsize bases where there was frequent but shallow contact. With vastly different social norms, hygiene habits, and mannerisms, Afghans often found Americans disrespectful and arrogant, while the Americans could be openly contemptuous of their counterparts. “I thought Iraqis were the worst people in the world, and then I came here,” one young soldier with the 101st Airborne told me in Kandahar in 2011, expressing a sentiment typical among the troops.

The friction correlated with the rise in green-on-blue violence. In 2009, only 10 percent of Afghan army units were partnered, but in early 2012, when insider attacks peaked, that figure was close to 90 percent. (A spokesman for ISAF says it is “not correct to link the two” and that ISAF’s partnering strategy “began long before the increase in insider attacks in 2012.”)

Buck and his unit worried about their safety almost from the start. Insider attacks were happening all over the country, and the Taliban was stepping up efforts to infiltrate the Afghan army and police. In April 2012, a member of the Afghan Local Police—one of the US-backed militias that proliferated in southern Afghanistan as part of the counterinsurgency strategy—walked into a police station in southern Garmsir wearing a suicide vest and killed 10 Afghan police officers and civilians.

In June, while Buck was on guard duty, he asked an Afghan cop for his ID, per standard procedure, and the man refused. They ended up in a shouting match, and when Buck was later ordered by his Marine superiors to apologize, the Afghan policeman refused to shake his hand. Buck was badly rattled by the incident. “He just had this feeling,” Oliver recalled.

Back in Oceanside, Greg Sr. noticed his son sounded increasingly worried in their weekly phone calls. “I don’t feel safe here at all. I want to come home,” Buck told his father during one conversation. “I’m telling you, something’s going to happen to me here.”

Then he asked, where is your brother Mohammad? He replied, he is at home. Then the boy became very happy. He will accompany me, he thought, and we’ll start studying together. Then he told the younger cousin to go and ask his brother to come, and tell him that I’m waiting here.

Convinced that the answer to Aynuddin’s mystery lay in the time he spent as a runaway, I visited the Lashkar Gah Training Center. Its low-slung barracks look out onto a wide gravel lot, where Afghan police recruits and their ISAF trainers were practicing mock Taliban ambushes, each side pointing empty weapons and yelling, “Bang, bang.” Mohammad, a cousin of Aynuddin’s, was halfway through the two-month police-training course.

“He was a good person and a dear friend,” Mohammad said, folding his chunky army boots under himself as we sat down on the gravel. He had the faintest wisp of a mustache, but claimed that he was 19. “He was having problems at home and couldn’t live there anymore,” he told me. “First, we joined with the local police.”

On the day he ran away from home in early 2012, Aynuddin stayed the night in a park. He spent the next day walking 20 miles to Mohammad’s house in Marjah, where he convinced his cousin to join him. It’s not uncommon for runaways to end up with the police, who are desperate for recruits. The day after leaving Marjah, the teenagers joined a band of Afghan Local Police militiamen.

At first, it seemed an exciting adventure. They smoked hashish with the older policemen, cruised around in American-supplied pickup trucks, and fired automatic weapons in the nearby desert. Aynuddin was a good shot, Mohammad recalled, strong enough to handle a light machine gun. Once, he even took part in a gunfight with the Taliban.

But the boy’s bookishness was out of place among the illiterate police, and he longed to continue his education. At night, he sometimes called into local radio stations to recite poems that he had written. “They were about loneliness and love,” Mohammad said, laughing. “What else is there to write about?”

Aynuddin also confided to him that he had been physically abused by Isamuddin and his other older brothers, who treated him like a servant. (Perhaps that, not the traffic accident, was the real reason for his violent temper.) Normally calm and friendly, Aynuddin sometimes grew bizarrely aggressive, particularly after smoking hash. Once, fed up with being ordered to feed a dog that lived outside the Marjah police station, he shot the animal dead with his AK-47.

A couple months after he ran away and joined the Afghan Local Police, Aynuddin’s family found him and pressured the militia to send him and his cousin home. Initially, he was calmer with his family, though he wouldn’t speak of his experiences with the police and sometimes stared into space, as if recalling troubling memories. One night, as he slept next to Shamshad, Aynuddin awoke and told his younger brother that he had just dreamt that he was a corpse, and that the people standing over him were about to take him to the graveyard. After a few weeks, the anger spells returned, and after another fight with his mother, he left home again.

This time, he headed south alone to Garmsir, where he joined another US-backed police unit for around two months. In early August 2012, Aynuddin arrived at the Garmsir police headquarters with the entourage of the newly appointed police chief, Sarwar Jan, several Afghan cops told me. The Marines had pushed Jan, a distant relative of Aynuddin’s, out of at least one previous posting for his alleged corruption and suspected dealings with the Taliban, but he was well connected politically. He was also rumored to be a sexual predator. “Some of the stuff with pedophilia and chai boys made the Marines sick to their stomachs,” one Marine officer told me. “His nickname was ‘OJ,’ because he was such a criminal.”

Afghan police at Garmsir told me that Aynuddin was always at Jan’s side, fetching tea and anything else the commander required. At night, they said, he slept in Jan’s room. (When I tracked him down, Jan, who is serving a one-year house arrest sentence for allowing Aynuddin’s attack to happen on his watch, denied having any corrupt dealings or fondness for teenage boys.)

Around the same time that Aynuddin arrived in Garmsir, Buck’s unit got word that they would be leaving on August 12, two months ahead of schedule. The countdown started. A week before their departure, Oliver took a video of Buck lying shirtless in his bottom bunk, staring at the plywood above his head where, like a prisoner, he had drawn lines counting off the days they had spent in Garmsir. He placed his finger against them, ticking off the legs of their journey home, via Helmand’s Camp Dwyer and the Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan. “Seven days…Dwyer,” Buck murmured. “Ten days…Manas. Fourteen days…Hawaii! Oh, yeah!” he cried, wriggling in the bunk.

“If you burn yourself with hot milk, you will blow on yogurt. The Americans are afraid of us. The relationship is obviously broken. FOB Delhi is divided into compounds. We are all like dangerous segregated animals in a zoo.” ANP Ewaz Geldi, 29

When Aynuddin stepped into the gym, none of the Marines had time to grab their weapons. He fired two short bursts into Dickinson, knocking him flat. Then he swiveled and shot Buck and Richie. There was pandemonium as everyone scrambled to the back of the tent. “Go, go!” the Marine behind Oliver shouted. He squeezed through a narrow opening in the fence and sprinted to the police headquarters with two other Marines who escaped the tent, as more gunshots sounded. They pounded up the stairs, retrieved their rifles, and radioed for a medevac. Oliver grabbed his medical bag and started back down when he heard a staff sergeant named Cody Rhode yell, “I’m coming up!” Rhode was shot in the arms and legs but had managed to get out. The Marines put tourniquets on him, and then Oliver, carrying his bag, ran back to the gym, his thoughts on Buck and Richie.

Having emptied his magazine, Aynuddin scrambled back out into the yard. From the upper windows of the police station, Marines opened fire, pocking the concrete wall behind him as he dashed up the tan metal steps of a watchtower in the corner of the police compound, looking for a way out.

Asadullah Khanay, a diminutive police sergeant with curly black hair, was sitting inside the watchtower, taking post-prandial tea with his friend Atiqullah, when suddenly they heard gunshots outside. Then Aynuddin burst into the room. He pointed his AK-47 at them. “Will you do jihad with me against the infidels, or will I have to kill you too?” he said.

“Of course we’ll help you, let’s do it!” Khanay shouted, leaping to his feet and pulling out his pistol. Drawing closer to the wide-eyed teenager, he suddenly seized the barrel of Aynuddin’s rifle and flicked the safety on, then yanked out the magazine. Atiqullah came to his aid and together they tore the weapon from Aynuddin’s grip. Aynuddin lunged past them, jumping through an open window onto a walkway that ringed the watchtower, just as a handful of armed Marines kicked in the door. Khanay and Atiqullah threw their hands up. Seeing the open window, the Marines ran around the side of the watchtower and tackled Aynuddin. They threw him down, and Khanay offered his scarf to bind Aynuddin’s hands behind his back.

“Let me go—don’t give me to the foreigners!” Aynuddin screamed as he was pinned down.

“You idiot—you could have gotten all of us killed,” Khanay shouted back.

Below in the gym, Oliver found Buck and Dickinson, both lifeless. But Richie Rivera had managed to crawl out into the yard. He was still alive. They got him on a stretcher, and Oliver and the other medics administered CPR. “Richie,” he recalled, “died pretty much in my hands.”

“It’s like we’re conducting an assault,” grumbled Major Mike Martin, a burly, ruddy-cheeked officer from South Carolina, as he surveyed the armed Marines beside him, some of them wearing body armor and helmets. Martin commanded the team that had taken over for Buck’s unit, and though his men appeared as if they were outfitted for combat, they were merely preparing to visit their Afghan allies.

Three months had passed since Aynuddin’s attack, and the Marines were no longer taking any chances. The PAT had cleared out of the police headquarters and now lived elsewhere on the base. Now Martin and his men carried locked-and-loaded weapons when they trained the Afghan police, a task that had become even more difficult as a result of the limited time they spent with the cops.

Martin and his team walked around to the front of the station, where they found a few policemen relaxing on plastic lawn chairs in the mild winter sun. Several Marines climbed up into the watchtower to stand watch while their fellow trainers chatted with the police. “That incident set us back by a lot,” Martin said.

As deaths from insider attacks mounted in 2012, ISAF seemed unwilling to abandon partnering, which was central to its entire Afghanization program. Instead, it pushed the Afghans to develop better counterintelligence and vetting procedures. “They couldn’t clamp down too hard on recruitment,” explains Smith, the International Crisis Group analyst, “because high attrition means they need to keep pumping fresh recruits into the ranks.”

A few weeks after the attack on Buck and his unit in Garmsir, ISAF finally ordered a series of protective measures—like “guardian angels,” soldiers who stand watch whenever Afghans and American forces are together—and a temporary halt to working with Afghan Local Police, whose low level of training and local ties made them particularly susceptible to Taliban infiltration. Partnering has also been drastically curtailed: Only 23 percent of Afghan army units are partnered today, and insider attacks have declined this year, with nine reported incidents as of September, the most recent of which killed three Americans.* (ISAF claimed there has been no “long-term decrease in partnering due to insider attacks” and said the Afghan security forces “are now demonstrating their capacity as they take the lead in fighting.”)

But the result has been to leave the Afghan strategy half-finished: A vast and unsustainably expensive force has been mobilized and equipped, but it remains poorly disciplined and widely corrupt, and overlaps uneasily with a constellation of even worse-trained militia forces. With the majority of foreign forces due to depart Afghanistan in a little more than a year, it’s anyone’s guess whether the Afghan forces can stand on their own. If they can’t, and the security vacuum causes Afghanistan to revert to chaos, insider attacks will have been partly to blame.

“The question you gotta ask is, is there any more juice left to squeeze from the orange?” Martin said. “Is this as good as it’s going to get?”

In October 2012, Aynuddin’s family traveled to the headquarters of the Red Cross in Kandahar, where, through a video conference link, they were able to speak to Aynuddin, who looked confused and small in his prison garb. Though there were many witnesses to the shooting, he denied being involved. He’s being held at Bagram Airfield, where he has been practicing his English with his captors. His fate, like that of the rest of the Afghans held at Bagram, is uncertain. The Karzai government is adamant that the United States transfer custody of all prisoners on Afghan soil prior to the end of 2014. At that point, Aynuddin might face the abuse and torture that is rampant in Afghan prisons—or he might, given his youth, just be released.

It remains unclear why Aynuddin committed his crime. His family and friends believe he was simply a confused, angry boy prone to lashing out. Most of the Marines that I spoke with, however, believed that he was recruited and trained by the Taliban. The fact that the attack occurred only a couple of weeks after he arrived at the headquarters, and that it happened the same day another Afghan police officer attacked and killed three Marines in northern Helmand, has fueled their suspicions. But none of the senior Marines that I spoke with knew for sure about a Taliban link. Indeed, the basic uncertainty surrounding Aynuddin’s case shows just how little anyone at ISAF understood about why these attacks happened, or how they could have been prevented.

That night last August, when Greg Buckley Sr. stood in his kitchen and listened to the grave-faced Marines, his first thought, after a stunned moment when the world seemed to go silent and film over with gray, was that someone was playing a joke on him, and that idea filled him with rage.

“Listen, I’m gonna tell you this now,” he said. “If you guys are here fucking with me, not one of you is going to make it out of my house.” But he saw the truth on their faces.

There were days of madness after that, not the raving kind but a sort of fugue, as the family was borne up in a sea of relatives and friends who swarmed the house and filled the street outside in the hundreds.

It was on the way to Dover Air Force Base, to watch his son’s body come off a plane in a box, that Buckley’s anger returned. A onetime boxer, he’d always had a pugilistic streak. As Buckley and his family waited in the hangar, a tall, blond general approached and knelt in front of him. “Mr. Buckley, I just want to give you my condolences.”

Buckley stabbed his fingers into the general’s medals. “Do me a favor,” he said, “and get the fuck up off your knee and get the fuck outta my face. ‘Cause you motherfuckers had my son fucking murdered.”

As he recounted this story in New York City, the hum of the restaurant grew louder—they were filming some kind of reality show behind the counter, and a celebrity chef was berating a contestant’s burger. Buckley rested his elbows on the checkered tablecloth and pressed his ?ngers into his temples. “You signed up to join the Marine Corps, and you might die, and I’m cool with that,” he said, his voice softening. It’s the way it happened that eats at him. Greg Jr. died carrying out a strategy that seems likely to fail, in a war that may never be won, at the hands of a troubled teenager whose motives may never be clear. “I just don’t want this kid, my son, to go out like that.”

*The number of incidents has been updated since the publication of the original article, which ran under the headline “Friend or Foe?” in our November/December 2013 print issue.