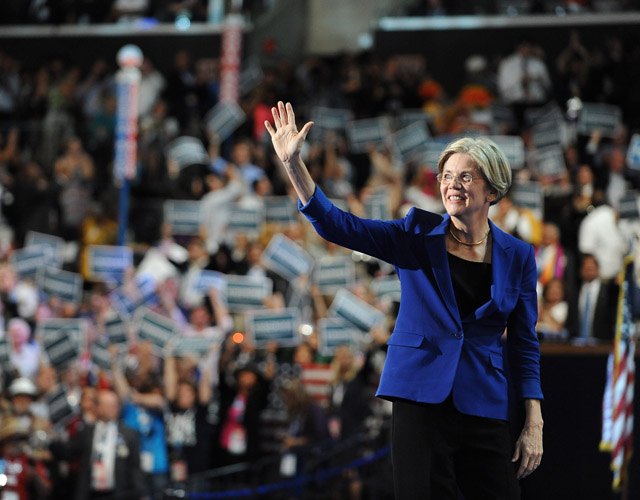

Jay Mallin/ZUMA

Five years after the financial crash, most congressional Democrats seem content to live with the status quo. They tackled financial reform in 2010 when they passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, and they’d prefer to leave the nitty-gritty details of keeping banks in check to federal agencies rather than pass new legislation.

But Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) won’t be so easily assuaged. On Tuesday, she delivered a speech to a room full of academics, consumer advocates, and Senate aides that criticized federal regulators for failing to meet the deadlines to write rules regulating banks, as outlined in Dodd-Frank. “Since when does Congress set deadlines, watch regulators miss most of them, and then take that failure as a reason not to act?” she said. “I thought that if the regulators failed, it was time for Congress to step in. That’s what oversight means. And that’s certainly a principle that would have served our country well prior to the crisis.”

She noted that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the agency she conceived of and helped guide to formation, has met its deadlines for writing rules. But the other federal agencies have been an utter failure at keeping to the schedule laid out by Dodd-Frank. A recent report by Davis Polk found that 60 percent of deadlines had been missed. Thirty percent of Dodd-Frank-mandated rules haven’t even been proposed yet, let alone finalized.

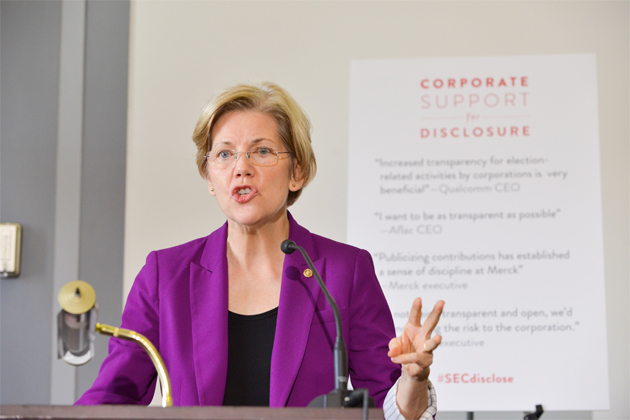

Warren spoke at an event assessing the state of financial reform hosted by Americans for Financial Reform (AFR) and the Roosevelt Institute. The two organizations released a 125-page report Tuesday outlining where Dodd-Frank has succeeded and failed, with a heavy emphasis on where the act failed to tame the biggest banks’ risky activities and how they still expose the entire economy to risk should they collapse.

Warren warned that Dodd-Frank hasn’t solved “too big to fail”— the idea that certain financial institutions are so central to the operation of the economy that if, like AIG in 2008, their balance sheets collapse, the US government must step in to keep them solvent and prevent a system-wide collapse. According to Warren, the problem has actually gotten worse since the recession began. Bank consolidation is even more pronounced five years post-crash. “Today, the four biggest banks are 30 percent larger than they were five years ago,” she said. “And the five largest banks now hold more than half of the total banking assets in the country.”

Instead of relying on regulators to write strict rules, Warren pushed the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act, a bill she’s introduced alongside Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and other senators that would force commercial financial institutions to wall off standard bank deposits from the riskier activities of investment banking, such as the swaps that sunk the economy in ’08.

“The new Glass-Steagall Act would attack both ‘too big’ and ‘to fail,'” Warren said Tuesday. “It would reduce failures of the big banks by making banking boring, protecting deposits, and providing stability to the system even in bad times. And it would reduce ‘too big’ by dismantling the behemoths, so that big banks would still be big—but not too big to fail or, for that matter, too big to manage, too big to regulate, too big for trial, or too big for jail.”

Dodd-Frank left the “too big” portion largely untouched, but its authors at least tried to solve the problems of bank failure causing systematic harm. The AFR/Roosevelt report elaborated on several ways the act might reduce the chance of another government bailout, though the authors were pessimistic that the problem has been solved. In one section, Stephen Lubben of the Seton Hall University School of Law explains how the biggest banks are global institutions, limiting the government’s ability to unwind failing businesses, as Dodd-Frank is written, and leaving regulators to lay out guidelines that overestimate their ability to take over a bank and sell off its assets. “Assuming rationality in a financial crisis is a doubtful solution to a difficult problem,” Lubben writes.

Roosevelt’s Mike Konczal, one of the report’s editors, writes about how higher capital requirements, essentially a cap mandating the amount of money banks must keep on hand in relation to how much debt they have outstanding, could solve many of the problems the economy encountered in 2008. “Capital requirements are a clean, straightforward way of increasing the stability of the financial sector,” he writes. Yet, according to Konczal, the level of leverage in the rules discussed has been far too low, while not forcing banks to hedge against all of their assets, such as derivatives.

But in the end, technical fixes from the federal regulators aren’t going to be enough to solve the problem. “I think the biggest banks need to be smaller and less complex,” former House member Brad Miller said at one point during the event, summing up the general wonky assessments of the report in plain language. Preventing another crash requires an overhaul of how we conceive of our banking institutions, and that only comes from further congressional action.

“We should not accept a financial system that allows the biggest banks to emerge from a crisis in record-setting shape while working Americans continue to struggle,” Warren said. “And we should not accept a regulatory system that is so besieged by lobbyists for the big banks that it takes years to deliver rules and then the rules that are delivered are often watered-down and ineffective. What we need is a system that puts an end to the boom and bust cycle. A system that recognizes we don’t grow this country from the financial sector—we grow this country from the middle class.”