"They first had to win the moral high ground": The Reverend William BarberGerry Broome/AP Photo

On a recent Sunday afternoon, the Reverend William Barber II reclined uncomfortably in a chair in his office, sipping bottled water as he recovered from two hours of strenuous preaching. When he was in his early 20s, Barber was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, a painful arthritic condition affecting the spine. Still wearing his long black robes, the 50-year-old minister recounted how, as he’d proclaimed in a rolling baritone from the pulpit that morning, “a crippled preacher has found his legs.”

It began a few days before Easter 2013, recalled Barber, pastor at the Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and president of the state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). “On Maundy Thursday, they chose to crucify voting rights,” he said.

“They” are North Carolina Republicans, who in November 2012 took control of the state Legislature and the governor’s mansion for the first time in more than a century. Among their top priorities—along with blocking Medicaid expansion and cutting unemployment benefits and higher-education spending—was pushing through a raft of changes to election laws, including reducing the number of early voting days, ending same-day voter registration, and requiring ID at the polls. “That’s when a group of us said, ‘Wait a minute, this has just gone too far,'” Barber said.

On the last Monday of April 2013, Barber led a modest group of clergy and activists into the state legislative building in Raleigh. They sang “We Shall Overcome,” quoted the Bible, and blocked the doors to the Senate chambers. Barber leaned on his cane as capitol police led him away in handcuffs.

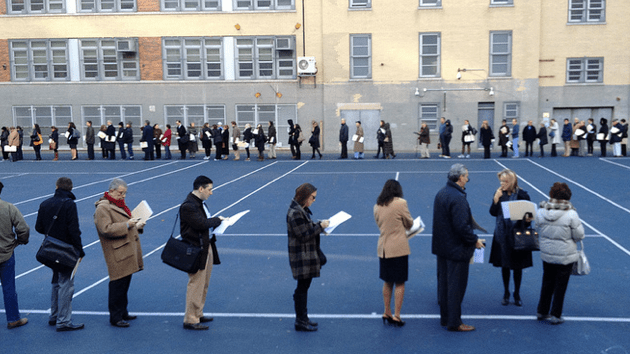

That might have been the end of just another symbolic protest, but then something happened: The following Monday, more than 100 protesters showed up at the capitol. Over the next few months, the weekly crowds at the “Moral Mondays” protests grew to include hundreds, and then thousands, not just in Raleigh but also in towns around the state. The largest gathering, in February, drew tens of thousands of people. More than 900 protesters have been arrested for civil disobedience over the past year. Copycat movements have started in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama in response to GOP legislation regarding Medicaid and gun control.

With Moral Mondays, Barber has channeled the pent-up frustration of North Carolinians who were shocked by how quickly their state had been transformed into a laboratory for conservative policies. “He believed we needed to kind of burst this bubble of ‘There’s nothing we can do for two years until the next election,'” explains Al McSurely, a longtime NAACP organizer. But what may be most notable about Barber’s new brand of civil rights activism is how he’s taken a partisan fight and presented it as an issue that transcends party or race—creating a more sustained pushback against Republican overreach than anywhere else in the country.

Barber’s activism is rooted in his family’s history. In the 1960s, his parents moved back to eastern North Carolina from Indianapolis to help desegregate the local schools. His father, also a preacher, taught science at a formerly all-white high school. His mother became the school’s first black office manager. Students called her “nigger” before they finally learned to call her “Mother Barber.”

Barber fears that Republican lawmakers’ efforts to expand private-school vouchers will resegregate the very schools his parents worked to integrate. As NAACP president, he helped pass legislation establishing same-day voter registration and expanding death penalty appeals—bills that Republicans repealed in the last legislative session.

In 1993, a flare-up of his condition left him hospitalized, and he spent the next dozen years relying on a walker to get around. Exercise, faith, and “a little miracle and medicine” fueled his recovery—along with a good health plan. “I never want to have health insurance and see other members of the human family denied,” he says. “It’s immoral.” He shakes his head at lawmakers who receive generous benefits only to try to deny their constituents access to Obamacare or expanded Medicaid. “The logic doesn’t compute.”

Barber says his emphasis on morality is inspired by his predecessors in the civil rights movement. “They first had to win the moral high ground, and they had to capture the attention and consciousness of the nation,” he explains. “When those two things came together, it gave space for people like Lyndon Baines Johnson, who was a segregationist, to step out of his normal pattern of politics into a new way.” Barber says that Moral Mondays’ broad appeal is reflected in state Republicans’ sagging popularity: A February poll found that just 36 percent of North Carolina voters approved of Gov. Pat McCrory’s job performance; 28 percent approved of the General Assembly’s.

With North Carolina Democrats still in disarray following their drubbing in 2012, some progressives are looking to Barber to lead them out of the wilderness. “It’s our job to take this energy and turn it into reality at the polls,” says Democratic Party chairman Randy Voller.

But to Barber, the movement’s success is not tied to the ballot box. Rather, it’s in moments like the cold Saturday morning in February when tens of thousands of people flooded the streets of the capital. Black, white, gay, and straight, they came from churches and synagogues wearing rainbow flags for marriage equality, pink caps for Planned Parenthood, and stickers reading “North Carolina: First in Teacher Flight.” When it was Barber’s turn to speak, the crowd fell silent.

“Make no mistake—this is no mere hyperventilation or partisan pouting,” he intoned, his voice rising and breaking. “This is a fight for the future and soul of our state. It doesn’t matter what the critics call us…They can deride us, they can try to deflect from the issue. And we understand that, because they can’t debate us on the issue. They can’t make their case on moral and constitutional grounds.”

This article has been updated.