Morris eased the pickup truck to the side of the road. The wide, busy thoroughfares of 1950s Wichita, Kansas, were just five miles southwest, but here on the largely undeveloped outskirts of the city, near the Koch family’s 160-acre property, the landscape consisted of little more than flat, sun-bleached fields, etched here and there by dusty rural byways. The retired Marine, rangy and middle-aged, climbed out of the truck holding two sets of scuffed leather boxing gloves.

“Okay, boys,” he barked, “get outside and duke it out.” David and Bill, the teenage Koch twins, were at each other’s throats once again. Impossible to tell who or what had started it. But it seldom took much. The roots of the strife typically traced to some kind of competition—a game of hoops, a round of water polo in the family pool, a footrace. They were pathologically competitive, and David, a gifted athlete, often won. Everything seemed to come easier for him. Bill was just 19 minutes younger than his fraternal twin, but this solidified his role as the baby of the family. With a hair-trigger temper, he threw the tantrums to match.

David was more even-keeled than Bill, but he knew how to push his brother’s buttons. Once they got into it, neither backed down. Arguments between the twins, who shared a small room, their beds within pinching range, transcended routine sibling rivalry. Morris kept their boxing gloves close at hand to keep them from seriously injuring each other when their tiffs escalated into full-scale brawls. The brothers’ industrialist father had officially hired the ex-soldier to look after the grounds and livestock on the family’s compound. But his responsibilities also included chauffeuring the twins to movies and school events, and refereeing the fights that broke out unpredictably on these outings.

Morris laced up one brother, then the other. The boys, both lean and tall, squared off, and when Morris stepped clear, they traded a barrage of punches. A few minutes later, Morris reclaimed the gloves and the brothers piled breathlessly into the cab. He slipped back behind the wheel and pulled out onto the road.

Pugilism was an enduring theme in the family. The patriarch, Fred Koch—a college boxer known for his fierce determination—spent the better part of his professional life warring against the dark forces of communism and the big oil companies that had tried to run him out of the refining business. As adults, Fred’s four sons paired off in a brutal legal campaign over the business empire he bequeathed to them, a battle that “would make Dallas and Dynasty look like a playpen,” as Bill once said.

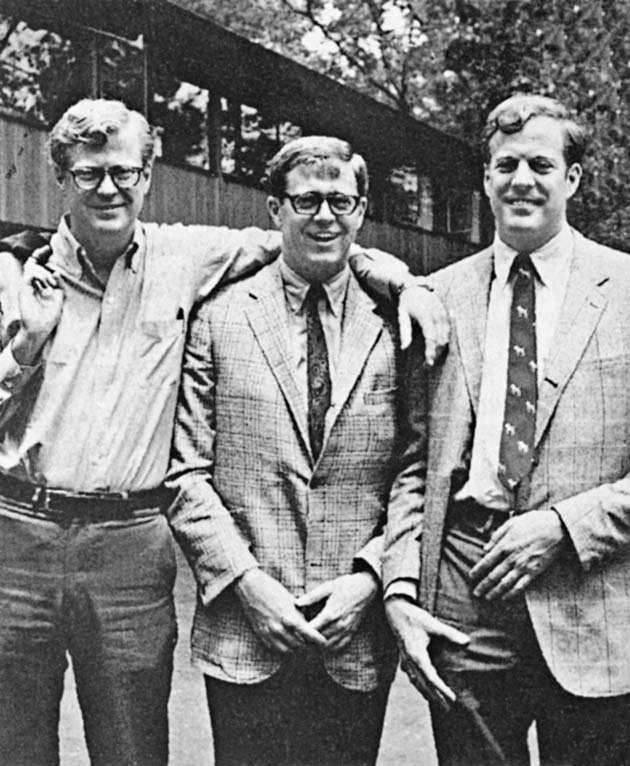

The roles the brothers would play in that drama were established from boyhood. Fred and Mary Koch’s oldest son, Frederick, a lover of theater and literature, left Wichita for boarding school after 7th grade and barely looked back. Charles, the rebellious No. 2, was molded from an early age as Fred’s successor. After eight years at MIT and a consulting firm, Charles returned to Wichita to learn the intricacies of the family business. Together, he and David would build their father’s Midwestern company, which as of 1967 had $250 million in yearly sales and 650 employees, into a corporate Goliath with $115 billion in annual revenue and a presence in 60 countries. Under their leadership, Koch Industries grew into the second-largest private corporation in the United States (only the Minneapolis-based agribusiness giant Cargill is bigger).

Bill, meanwhile, would become best known for his flamboyant escapades: as a collector of fine wines who embarked on a litigious crusade against counterfeit vino, as a playboy with a history of messy romantic entanglements, and as a yachtsman who won the America’s Cup in 1992, an experience he likened, unforgettably, to the sensation of “10,000 orgasms.” Koch Industries made its money the old-fashioned way—oil, chemicals, cattle, timber—and in its dizzying rise, David and Charles amassed fortunes estimated at $41 billion apiece, tying them for sixth place among the wealthiest people on the planet. (Bill ranks 377th on Forbes‘ list of the world’s billionaires.) The company’s products would come to touch everyone’s lives, from the gas in our tanks and the steak on our forks to the paper towels in our pantries. But it preferred to operate quietly—in David’s words, to be “the biggest company you’ve never heard of.”

But if Charles and David’s industrial empire stayed under the radar, their political efforts would not remain so private. After spending decades quietly trying to mainstream their libertarian views and remake the political landscape, they burst into the headlines as they took on the Obama administration and forged a power center in the Republican Party.

Politicians, as one of Charles’ advisers once put it, are stage actors working off a script produced by the nation’s intellectual class. Some of the intellectual seeds planted by the Kochs and their comrades would germinate into one of the past decade’s most influential political movements: Though the intensely private brothers downplay any connection, they helped to provide the key financing and organizational support that allowed the tea party to blossom into a formidable force—one that paralyzed Congress and ignited a civil war within the GOP. After backing a constellation of conservatives, from Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker to South Carolina’s Jim DeMint, Charles and David mounted their most audacious political effort to date in the 2012 presidential campaign, when their fundraising network unleashed an estimated $400 million via a web of conservative advocacy groups.

Just as their father, a founding member of the John Birch Society, had once decried the country’s descent toward communism during the Kennedy era, the brothers saw America veering toward socialism under President Obama. Charles, entering his late 70s, had not only failed to see American society transformed into his libertarian ideal; with this new administration, things seemed to be moving in the exact opposite direction. Now he and David, along with other allies, would wage what he described as the “mother of all wars” to defeat Obama and hand Republicans ironclad congressional majorities.

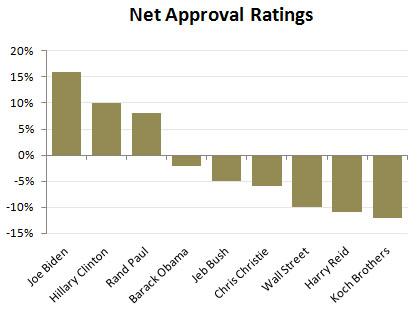

Yet for all the attention the Kochs—including the “other brothers,” Frederick and Bill—have received, America knows little about who they really are. Charles and David have gained a reputation as cartoonish robber barons, powerful political puppeteers who with one hand choreographed the moves of Republican politicians and with the other commanded the tea party army. And like all caricatures, this one bears only a faint resemblance to reality.

As with America’s other great dynasties, the Kochs’ legacy (corporate, philanthropic, political, cultural) is far more expansive than most people realize, and it will be felt long into the future. Already, the four brothers have become some of the most influential, celebrated, and despised members of their generation. Understanding what shaped them, what drove them, and what set them upon one another requires traveling back to a time when the battles involved little more than a pair of boxing gloves.

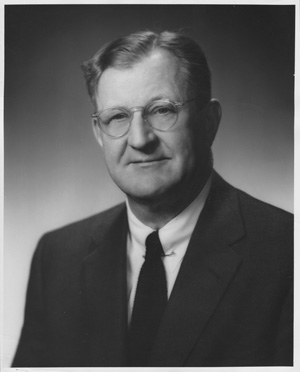

Fred Koch came up in a place where sometimes all that separated prosperity from poverty was an unfortunate turn in the weather. Quanah, Texas, located just east of the panhandle and eight miles from the Oklahoma border, was a town of strivers, and Fred watched his father’s rise from penniless Dutch immigrant to successful newspaper owner. By the time his four sons were born—Frederick in 1933, Charles in 1935, David and Bill in 1940—Fred’s technical talent and unrelenting ambition had made him the co-owner of a multimillion-dollar oil engineering firm.

Fred told his sons he wanted them to experience “the glorious feeling of accomplishment.” If he handed them everything, what would motivate them to make something of themselves? “He wanted to make sure, because we were a wealthy family, that we didn’t grow up thinking that we could go through life not doing anything,” Charles once recalled. Fred’s mantra, drilled repeatedly into their minds, was that he had no intention of raising “country-club bums.”

Though his children grew up among Renoirs and Thomas Hart Bentons on an estate across from the exclusive Wichita Country Club, Fred went out of his way to make sure they did not feel wealthy. “Their father was quite tight with his resources,” recalled Jay Chapple, a childhood friend of the Koch twins. “Every family was getting a TV set that could possibly afford one, but Fred Sr. just said no.” The brothers received no allowances, though they were paid for chores. “If we wanted to go to the movies, we’d have to go beg him for money,” David once told an interviewer. In the local public school, where the Koch boys began their educations alongside the sons and daughters of blue-collar workers from the Cessna and Beech factories, it was their classmates who often seemed like the rich ones, he remembered: “I felt very much of a pauper compared to any of them.”

Fred rarely displayed affection toward his sons, as if doing so might breed weakness in them. “Fred was just a very stiff, calculated businessman,” Chapple said. “I don’t mean this in a critical way, but his interest was not in the kids, other than the fact that he wanted them well educated.” He was not the kind of dad who played catch; he was the type of father, one Koch relative recalled, who taught his children to swim by throwing them into the pool and walking away. “He ruled the boys with an iron fist.”

Fred traveled frequently on business, but when he was home, the household took on an air of Victorian formality. After work, Fred often retreated to his wood-paneled library, its shelves filled with tomes on politics and economics, emerging promptly at 6:30 p.m., still in coat and tie, for dinner in the formal dining room. “He just controlled the atmosphere,” Chapple recalled. “There was no horseplay at the table.”

Every dictatorship has its dissident, and Frederick played this part early on. While the three younger boys took after their father, he gravitated toward his mother’s interests. Mary Robinson Koch helped to nourish Frederick’s artistic side, and when he grew up they often took in plays and attended performing arts festivals. Frederick was a student of literature and a lover of drama who liked to sing and act. He wasn’t athletic, displayed no interest in business, and loathed the work-camp-like environment fostered by his father, with whom he shared little beyond a love of opera.

By the late 1950s, when Frederick was in his 20s, many in the family’s circle of friends assumed that he was gay. “You know, those things, especially in an environment like Wichita, were almost whispered,” says someone who spent time with the family and their friends during that era. (Frederick told me he is not gay.)

In the 1960s, mention of Frederick even vanished from one of his father’s bios: “He and Mrs. Koch have three sons,” it read. “Charles, William, and David.”

Fred’s disappointment in his eldest son caused him to double down on Charles, piling him with chores and responsibilities by the age of nine. “I think Fred Koch went through this kind of thing that ‘I must have been too affectionate; I must have been too loving, too kind to Freddie, and that’s why he turned out to be so effeminate,'” said John Damgard, who went to high school with David and remains close with David and Charles. “So he was really, really tough on Charles.”

“I think Mary did a lot to protect the twins,” Damgard added, but Charles grew up with the impression that he was being picked on. As an 11-year-old boy, pleading for his parents to reconsider, he was shipped off to the first of several boarding schools, this one in Arizona.

As Charles admits, there was little about his teenage self that suggested he was destined for greatness. He was smart, but with the type of unharnessed intellect that tends to land young men in trouble. He got into fights, stayed out late drinking and sowing wild oats. David has called his older brother a “bad boy who turned good.” When it came time for high school, his exasperated parents sent him to Culver Military Academy in northern Indiana, an elite military school that had a reputation for taking in wild boys and spitting out upright, disciplined men (notable alumni include the late New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, actor Hal Holbrook, and Crown Prince Alexander II of Yugoslavia). Charles considered it a prison sentence, and during his junior year he was expelled after drinking beer on a train ride to school after spring break.

Asked later how old Fred took the news, the best Charles could say was, “I’m still alive.” Fred banished Charles to live with family in Texas, where he spent the remainder of the school year working in a grain elevator until, after some begging, he was reinstated at Culver.

When Charles became Fred Koch’s work-in-progress, he also became a lightning rod for his youngest brother’s jealousy. Bill was in some respects the most cerebral of the brothers, but he was also the most socially awkward and emotionally combustible. In his baby book, Mary had scrawled notations including “easily irritable,” “angry,” and “jealous.” As a young boy, Bill resorted to desperate gambits for attention. Once, according to Charles, when Mary warned her son to take a hog’s nose ring out of his mouth, Bill proceeded to gulp it down instead, necessitating a trip to the hospital.

Bill’s volatile emotions made it difficult for him to concentrate in school, and his worried parents eventually sent him to a psychologist, who advised that the only way to help Bill was to remove the source of his smoldering resentment—Charles. “We had to get Charles away [to boarding school] because of the terrible jealousy that was consuming Billy,” Mary told the New York Times‘ Leslie Wayne in 1986.

Bill recalled a Lord of the Flies-like childhood, in which his parents were frequently away—Fred to travel, Mary to attend social events—leaving him and his brothers in the care of the household help “to grow up amongst ourselves.” He remembered Charles as a mischievous bully who perched astride the family storm cellar during backyard games of King of the Hill and flung his brothers down to the ground whenever they tried to scramble to the top. Still, Bill idolized his older brother, though Charles made it painfully clear that he preferred David’s company.

Bill and David were twins, but David and Charles were natural compatriots. David was self-confident and athletic, with a mild temperament and a contagious, honking laugh. “Charles and David were so much alike, they were always really good friends. And Bill probably felt a little left out,” said their cousin Carol Margaret Allen. “Charles always had quite a following of girls, and so did David. And Bill—I think he would have liked to have had more girls following him. He was not as gregarious and outgoing.” Awkward and uncoordinated, Bill spent his childhood trying to keep up with his brothers. His self-esteem plummeted. “For a long time,” he later reflected, “I didn’t think I was worth shit.”

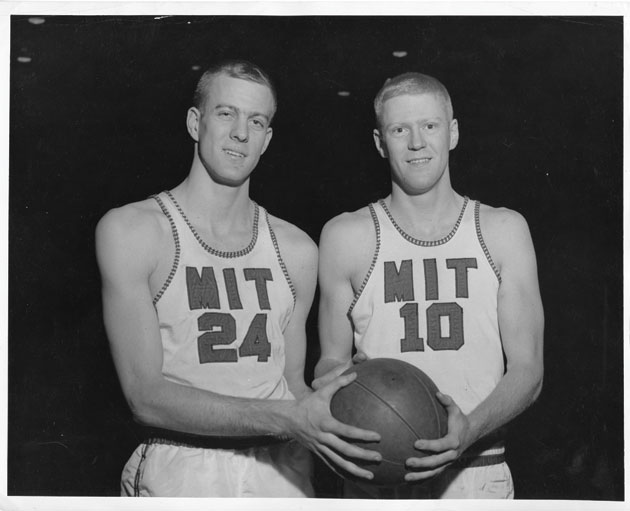

When it came time for the twins to attend prep school, they had their pick of prestigious institutions. David chose Deerfield Academy, a boarding school in northwestern Massachusetts that groomed East Coast Brahmins for the Ivy League. He credited the school, where he would distinguish himself on the basketball and cross-country teams, with transforming him “from an unsophisticated country boy into a fairly polished, well-informed graduate.” But Bill opted for Culver Military Academy, Charles’ alma mater. This alarmed Mary, who later confided to an interviewer that her son had become unhinged in his fixation on Charles.

“This was not a lovey-dovey family,” mused a member of the extended family. “This was a family where the father was consumed by his own ambitions. The mother was trapped by her generation and wealth and surrounded by alpha males. And the boys had each other, but they were so busy in pursuit of their father’s approval that they never noticed what they could do for each other.”

“Everything,” the relative added, “goes back to their childhood. Everything goes back to the love they didn’t get.”

On Christmas Day 1979, the four brothers, now aged 39 to 46, gathered in the dining room of their childhood home, the long table set with lace placemats and gold-rimmed crystal wine glasses. Also at the table were Charles’ wife, Liz, and Joan Granlund, the former model who’d become Bill’s secretary and girlfriend.

As was the family custom, Mary was hosting the Christmas dinner. Fred, who had died of a heart attack 12 years before, peered down from an oil painting on a nearby wall. But over the course of the evening, the festive mood evaporated, largely thanks to Bill.

Ever since joining Koch Industries in 1974, Bill had felt like the third and lesser wheel to David and Charles. He brooded over his role within the company, as well as over how Mary, who had just turned 72, planned to distribute her estate.

Seated across from his mother, Bill began to vent. Growing up, he had perceived Mary as cool and distant. Now he blamed her for laying the foundation for his emotional turmoil. She had not loved him; she had treated him unfairly. According to Charles, Bill also pressed her on the disposition of the family’s art collection. Their father had given Charles some paintings before his death; Bill insisted Mary even things out by leaving more of the collection to him.

Charles tried to calm his brother down: “I’m not going to fight you over any property, but just leave Mama alone.” Bill laid into Charles, too, whom he faulted for running their father’s company like a dictator. Fred may have selected Charles as his successor, but Koch Industries belonged to all of them.

Mary struggled to hold back tears. The discord, occurring on one of the few occasions when the Kochs still gathered as a family, finally overcame her. Sobbing, she pushed back from the table and hurried from the room.

It was the last Christmas the Kochs spent together.

The family business, which Charles had named Koch Industries in his father’s honor, had grown at a staggering rate with Charles at the helm. One of his first major deals was the acquisition of Great Northern Oil Company, owner of a Minnesota-based refinery that had ready access to a steady supply of Canadian crude. Fred had purchased a 35 percent stake in 1959; to gain a majority for the buyout, Charles had joined forces with his father’s old friend, Texas oilman J. Howard Marshall II, who swapped his 16 percent share in Great Northern for Koch Industries stock. The refinery became a company cash cow, fueling Charles’ expansion into natural gas and petrochemicals and pipelines. Koch had grown into a large company, but its success lay in the fact that it could still operate like a small one: Where its rivals lumbered along, it could make deals and strategic decisions without a laborious board approval process, moving decisively and swiftly.

Perhaps too swiftly for Bill. He’d risen from salesman to head the company’s mining subsidiary, Koch Carbon, and like Charles had a reputation for being highly analytical. But in meticulously studying every facet of an issue, he could be prone to waffling. He sought the opinions of high-priced consultants, commissioned studies, and snowed in managers with reports and memorandums. He asked endless questions, many of them astute, but to what end? At Koch, it was results that mattered. Profits. And the division Bill ran, according to Charles, was not faring so well.

Bill nevertheless pressed for more and more responsibility. William Hanna, the executive to whom Bill reported, noted: “It was important for Bill to be important.”

By 1980, Bill was openly dismissive of his brother, referring to him as “Prince Charles.” Over dinner one night at Boston’s Algonquin Club with his brother David and George Ablah—a family friend with whom the Kochs had recently joined in a $195 million real estate deal—Bill commented that Koch Industries had a reputation for screwing over its business partners. David was outraged. “You’ve got to retract that statement,” he said.

Bill’s criticisms—intemperate as they could sometimes be—were not merely rooted in sibling rivalry. He and other shareholders had developed some legitimate worries about the company’s direction. Koch Industries had run afoul of agencies ranging from the Department of Energy to the Internal Revenue Service, and it even faced a criminal indictment for conspiring to rig a federal lottery for oil and gas leases.

Bill had also grown troubled by the increasing amounts of company money Charles diverted to his “libertarian revolution causes”—causes Bill considered loony. “No shareholders had any influence over how the company was being run, and large contributions and corporate assets were being used to further the political philosophy of one man,” Bill said later.

Charles’ philosophy had been deeply influenced by their father, whose experiences helping to modernize the USSR’s oil industry in the early 1930s turned him into a rabid anti-communist who saw signs of Soviet subversion everywhere. A staunch conservative and Barry Goldwater backer, Fred was among the John Birch Society’s national leaders; Charles joined in due time, and by the ’60s was among a group of influential Birchers who grew enamored with a colorful anti-government guru named Robert LeFevre, creator of a libertarian mecca called the Freedom School in Colorado’s Rampart mountain range. From here, Charles fell in with the fledgling libertarian movement, a volatile stew of anarchists, devotees of the “Austrian school” of economics, and other radical thinkers who could agree on little besides an abiding disdain for government.

By late 1979, as tensions with Bill were escalating, Charles had become the libertarian movement’s primary sugar daddy. He had cofounded the Cato Institute as an incubator for libertarian ideas, bankrolled the magazine Libertarian Review, and backed the movement’s youth outreach arm, Students for a Libertarian Society. He had also convinced David to run as the Libertarian Party’s vice presidential candidate in the 1980 election (Bill had declined). David was able to pour unlimited funds into his own campaign, circumventing federal restrictions on political contributions.

Their father had loathed publicity, scrupulously guarding the family’s privacy. But, to Bill’s dismay, Charles and David’s activism was beginning to draw attention to the company and the family. Worse, at the very moment that the Energy Department was investigating Koch Industries for violating price controls on oil, David and his Libertarian Party running mate, Ed Clark, were on the campaign trail openly antagonizing the agency by calling for its eradication.

Beyond politics, Bill and other Koch shareholders also had concerns about liquidity. Bill was one of the richest men in America, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. But only on paper. He had needed to borrow money to buy a mansion near Boston. Nearly all of his net worth was locked up in a closely held private company. The market value of Koch stock, unlike that of publicly traded companies, was opaque. If any of Koch’s shareholders wanted to cash in their holdings, they would likely be forced to do so at an extreme discount.

Koch shares did pay a dividend (about 6 percent of the company’s earnings), but Bill considered it stingy. Charles’ growth-obsessed operating style called for plowing almost all earnings back into the company. This strategy expanded Koch Industries, but not the bank accounts of its shareholders—at least not immediately. Bill had interests he wanted to pursue: art, fine wine, yachting.

Bill began furtively meeting with Koch shareholders, some of whom shared his frustrations. The most obvious solution was taking the company public. Charles opposed this option. The last thing he wanted was more oversight from government bureaucrats.

On Thursday, July 3, 1980, an 11-page single-spaced letter landed on Charles’ desk. His blood pressure rose as he read: This was not just another of Bill’s regular, overheated missives. His brother was accusing him of keeping the board in the dark about key corporate matters, including its run-ins with regulators: “The directors and shareholders must look on helplessly as the corporation’s good name is dragged through the mud.”

Bill delved into the “extremely frustrating” liquidity issue, complaining that it was “absurd” that shareholders who were “extremely wealthy on paper” had almost no ability to utilize their assets. “What is the purpose of having wealth if you cannot do anything with it, especially when under our present tax laws on death they will undoubtedly end up in the hands of government and politicians?” If these problems were not solved, he warned, “the company will probably have to be sold or taken public.” Though the letter was addressed solely to Charles, Bill had circulated it to some of the shareholders. It was a declaration of war.

Six days later, on July 9, 1980, Charles took his customary place at the head of the long, polished wooden table in Koch Industries’ conference room. A large world map hung behind him. As usual, David sat to Charles’ left, and Sterling Varner, the company’s president, to his right.

Charles was known for his inscrutable impassiveness. But that afternoon, as the directors gathered for a board meeting, he was visibly angry. He had added a last-minute item to the agenda: “W.I.K. Has Leveled Serious Charges.”

During the contentious, hours-long meeting, the CEO went point by point through Bill’s memo. He accused his brother of angling for his job or Varner’s, and threatened to terminate Bill from the company, should he continue to cause unrest. Board members persuaded him to back down. But that fall, Charles dispatched emissaries to test the waters on whether Bill might consider selling his Koch shares. Bill declined. He had quietly lined up a coalition among Koch’s small circle of shareholders who agreed that the company’s board should expand from seven to nine members and take a more active role in overseeing management.

Most important, Bill had convinced Frederick to back his cause. Though partially disinherited by their father, a slight whose sting never went away, he still owned 14.2 percent of the company. (His brothers held 20.7 percent apiece.)

Frederick had his own tensions with Charles. After their father’s death, Charles had tried to buy him out of Koch Industries, and Bill alleged that Charles later resorted to more devious means—what he described as a homosexual blackmail attempt—to force his brother to sell his shares, a charge Charles has forcefully denied. (“Charles’ ‘homosexual blackmail’ did not succeed,” Frederick told me, “for the simple reason that I am not homosexual.”) Like Bill, Frederick was frustrated by his lack of control over his wealth. He had ambitions as a collector of art and antiques, and as a patron of the theater.

On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving in 1980, as dusk spilled across the plains surrounding Koch Industries’ Wichita headquarters, Bill stepped into Charles’ office. The brothers had scheduled a meeting to discuss liquidity, but Bill had other matters on his mind. He and other stockholders wanted a special shareholders meeting to, among other things, discuss Bill’s role in the company.

Charles was stunned. “You’re embarking on a program that’s going to destroy the company,” he seethed. “You won’t get your self-respect from attacking me.”

“Charles, let’s talk about what we want to do here.”

“Billy,” Charles countered, “you’re the type of person, if the bullet is ricocheting around the room and I say, ‘Duck!’ you want to debate the merits of the bullet.”

“Well, Charles, if you’re not going to call the meeting, then I’ll call it,” Bill finally said. He walked out, leaving his shell-shocked brother to fume and fret.

“One piece of advice my father gave me was that if you want someone to hate you, make him a lot of money,” Charles reflected later. “I didn’t understand it at the time. I understand it now.”

As Charles anxiously spent the holiday in Wichita with his family, David celebrated Thanksgiving in New York with Frederick, dining in the tenants-only restaurant in Frederick’s residence at 825 Fifth Avenue. The prewar co-op, designed in the 1920s by J.E.R. Carpenter, was one of the jewels of Fifth Avenue. It had a striking gabled roof of red terra-cotta tile, and a roster of upper-crust tenants.

David, whose vice presidential campaign had concluded earlier that month with the Libertarian ticket garnering 1 percent of the popular vote, lived in a UN Plaza duplex overlooking the East River. It was perhaps a 10-minute cab ride from Frederick, but the brothers tended to see each other only when their mother visited.

Today, David arrived 40 minutes ahead of the other guests. He wanted to fill his brother in on the recent strife between Bill and Charles and sound him out before the other guests arrived. “Fred listened attentively,” David recalled, “and I thought I was educating him for the first time about what was happening…Obviously, I was very naive.” Frederick told me he remained quiet because “at this point in time William had asked that I not reveal my reaction to the proxy fight.”

Charles had told David to keep an eye out for a letter announcing a shareholders meeting, and David fished it out of the mail the Friday after Thanksgiving. Bill’s name was on it, and so was Frederick’s.

David phoned his oldest brother. “I got this notice, Freddie, what’s going on?”

“I think it’s time for a change in the management of Koch Industries,” Frederick responded.

“Why do you want to fire Charles? He’s done a great job.”

“Well,” Frederick said, “are you surprised?”

On Saturday, David tracked down Bill. “Are you going to fire Charles?” David demanded. “No, we’re not,” Bill said.

“You’re lying,” David shot back. “You’re no brother of mine. I never want to have anything to do with you again.” He slammed down the phone.

That day, Charles heard from J. Howard Marshall II. The 75-year-old oil tycoon (best known for his marriage, 14 years later, to Anna Nicole Smith) was fiercely loyal to Charles. Marshall considered his decision to exchange his interest in Great Northern Oil for Koch stock “either the smartest or the luckiest thing I ever did.”

When Charles first informed him of Bill’s machinations, Marshall reassured him that neither of his sons—to whom he’d each gifted about 4 percent of the company stock—would be involved; they’d never cross their father. By Thanksgiving weekend, however, Marshall was shocked to learn that this was precisely what his elder son, Howard III, intended to do.

“What do we do now?” Charles asked.

“Well,” Marshall said, “there’s one thing that Howard III understands, and that’s money.”

Marshall would attempt to buy his stock back from his son. Without Howard III’s small, yet decisive, percentage of voting stock, the dissident shareholders would fall short of a majority.

When Bill learned of Marshall’s offer to his son, he offered to double it. A few agonizing days passed in Los Angeles, as Howard III pondered his next move—selling out to his dad or going against him. He had underestimated his father’s reaction to the shareholder insurrection. The prospect that his son might betray Charles had brought the old man to tears. Marshall looked frail as he laid out an $8 million cashier’s check in front of his son.

Family loyalty won out. Howard III rejected Bill’s offer and relinquished his Koch shares to his father. The balance of power had abruptly shifted: Charles’ faction controlled 51 percent of the company.

With Bill’s rebellion falling apart, he called off the special shareholders meeting. But Koch’s board did convene—to decide Bill’s fate. He’d crossed a line. His scheming had sparked a panic among Koch employees. In the boardroom, four men cast their vote, one by one, in favor of a motion to dismiss Bill.

But David wasn’t among them.

Over the past year, David had been torn between loyalty to his twin and fealty to Charles. He was furious with Bill for throwing the company into turmoil. But voting in favor of his dismissal would mean not just excommunicating Bill from the company, but also severing him from his life. He couldn’t bring himself to do that, and in the end he didn’t need to. The motion carried without him.

As Christmas 1980 approached, Bill sent gifts to his niece and nephew, Elizabeth and Chase, who were then five and three. Charles sent them back. When Bill called his brother to wish him a merry Christmas, Charles refused to come to the phone. Mary, as usual, had invited her sons to spend the holidays in Wichita, but Charles suggested that he and his family would not attend Christmas dinner if Bill and Frederick were there.

Since childhood, when Fred and Mary Koch sent their tantrum-prone son to a psychologist to get over his intense resentment of Charles, Bill had periodically lapsed into depressions. But the six months after his firing from Koch were among his darkest. Cloistered in his Dover, Massachusetts, mansion, he spent his days plotting with his lawyers and vegetating in front of the television. “This was the worst time I’d ever seen him in his life,” David recalled. “He was almost paralyzed, almost lifeless.”

David tried to help his brother get back on his feet, and when Bill and Joan urged him to visit a Boston psychiatrist they’d been seeing, he warily obliged.

The experience was surreal. The psychiatrist “spoke for about an hour and a half on why I needed psychiatric care,” David remembered. Growing angry that he had been lured into the visit under false pretenses, David finally forced the conversation back to Bill. “I asked a number of questions, and one was why was Billy so angry and nasty to our mother and made her cry all the time, upset her so much. He said, ‘Well, that’s a very positive sign because people with your brother’s problems have to climb out of their depression on the backs of the people they love the most.’

“I asked him about why Billy started this fight to get control of Koch Industries, and he said, ‘Well, Billy has a secret desire to fail’ and that he knew when he started this fight with Charles that he couldn’t win. I asked the doctor what I could do to help my brother and get him out of this terribly unhappy state that he was in, and he said, ‘There is nothing that you can do…until you straighten yourself out.'” David came away believing the psychiatrist had poisoned his twin’s mind and pushed Bill into the destructive showdown.

Back at Koch Industries, Bill’s firing had removed one threat to Charles’ hegemony. But Bill, Frederick, and the dissident shareholders (all extended family members) still controlled nearly half of the company. Like his father, Charles demanded loyalty from his business associates, and he couldn’t pursue his plans for Koch Industries while looking over his shoulder for the next coup attempt. The company and the dissidents needed a divorce. And it would be a messy one.

All options were now on the table, including taking Koch Industries public. Koch hired Morgan Stanley and Lehman Brothers to conduct parallel valuations of the company. Both investment banks determined that Koch shares should fetch in the vicinity of $160 a share, a price Bill (who stood to net about $376 million) and his allies deemed far too low.

To conduct his own analysis, Bill retained Goldman Sachs and the Boston-based consulting firm Bain & Company, where a young Mitt Romney was cutting his teeth. He also hired Arthur Liman, a high-profile litigator who later served as the chief counsel on the Senate’s Iran-Contra investigation. Bill realized that the threat of litigation might goose Koch to raise its offer, and bringing on Liman sent a clear signal. In October 1982, when negotiations had still failed to progress, Bill finally unleashed a lawsuit against Koch Industries and his brothers. He alleged a laundry list of mismanagement, including Charles’ lavishing of company funds on libertarian causes.

Charles and David retaliated with a $400 million countersuit, claiming that Bill and his supporters had used the media—especially an unflattering story in Fortune—to defame Charles by portraying him as “no less maliciously creative than the willful J.R. Ewing of the television show Dallas in devising ways to control his brothers and the family fortune.”

On May 25, 1983, the dissident shareholders, accompanied by a phalanx of lawyers and investment bankers, convened at the Marriott Hotel near New York City’s LaGuardia Airport. Desperate to rid itself of the suit and the problem shareholders, Koch Industries had substantially raised its bid, to $200 a share. Hoping to restore family peace, Fred’s cousin Marjorie Simmons Gray, who had been close to Mary Koch, urged that they settle. Frederick chimed in that he had better things to do than get dragged into a long and nasty lawsuit. Eventually, Bill reluctantly agreed.

Near midnight on June 4, 1983, the finalized agreement sat before Charles and Bill in the large conference room of Liman’s law firm. Koch would buy out the group for $1.1 billion, of which Bill would receive $470 million and Frederick $330 million. Such was the price of peace at Koch Industries.

Charles signed. So did Bill. Then he stood up from the conference table and smiled. “We’ve got our business affairs separated. The war is over,” he told his brother. They were relatively young men—Bill was 43 and Charles 47—with many years ahead of them. “We’re still brothers. I care about you.”

Bill extended his hand. Charles ignored the gesture. He turned and strode briskly out of the conference room, trailed by his lawyers. Bill crumpled heavily into his chair and buried his face in his hands.

The settlement had netted Bill nearly a half-billion dollars, yet he came to believe he’d been cheated. Two years later, he filed a lawsuit (later joined by Frederick) that would wend its way through the courts for a decade and a half, alleging that Charles and Koch Industries had obscured assets during the settlement talks and shortchanged the shareholders. He and Frederick would ultimately also drag their mother into court, naming her as a defendant in connection with a dispute over their father’s charitable foundation. “These lawsuits probably hurt [Mary] more than anything else except the death of my father,” David recalled in court testimony. “It was her worst nightmare fulfilled…It ate away at her like cancer.”

In March 1989, Mary suffered a mild stroke, which affected her balance and caused bouts of dizziness. Her blood pressure had been spiking, and her doctor prescribed medication for hypertension. Bill’s lawyer nevertheless subpoenaed Mary to testify in their suit over Fred Koch’s foundation. A tense courtroom scene played out in Wichita district court that April, as Mary’s doctor took the stand to back David and Charles’ position that their ailing mother should not be forced to testify.

“I don’t think she is ready for this sort of thing,” the physician, Dr. Albert Michelbach, testified. The court proceedings, he added, had affected “her physical and mental health.” And “the stress is going to cause her blood pressure to get out of control.” The opposing counsel grilled the doctor: “So, to the best of your knowledge, she’s still playing tennis on occasion?”—implying that, if so, she was healthy enough to testify.

“The callousness of counsel and of the plaintiffs,” marveled the Koch family’s lawyer, Bob Howard, “is almost beyond my experience.”

Tragedies bring some families closer. But Mary’s death, nearly two years after the stroke, did not lead to even a momentary thaw between her sons. At their mother’s funeral, Bill tried to greet Charles, but Charles once again ignored his outstretched hand.

After the funeral, the brothers held a wake at Mary’s home. Needing a moment to himself to mourn, Mary’s companion of several years, a local artist named Michael Oliver, descended a back staircase to the downstairs trophy room. He passed a pair of upright elephant tusks—from a bull Fred had bagged on safari—and the brass bell from a supertanker Charles had named for Mary. As Oliver stood alone among polar bear pelts and the heads of water buffalo, dik-dik, and ibex, Bill entered the room carrying an armload of files and papers. “These are my personal papers that I wanted to make sure I get back, because I know I won’t ever see them again,” he hastily explained, according to Oliver.

Oliver thought little of it as Bill hurried past, but he says Charles and David’s lawyers later told him that the stack of documents contained Mary’s calendars and other personal papers. Mary had put a provision in her will under which he and Frederick would be disinherited if they refused to drop their suit against Koch Industries—something Bill had no intention of doing. He would eventually contest the will in court, unsuccessfully alleging that Charles and the family lawyers had unduly influenced Mary.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the brothers unleashed a small army of private investigators on each other. (“We’re up against a very secretive company that operates like a cult,” a spokesman for Bill once told the New York Times.) Bill’s investigators, Vanity Fair reported, went so far as to establish a phony company and pose as headhunters in order to glean intelligence from ex-Koch Industries employees, donning body mics to secretly record their interviews. They also pilfered trash from the homes and offices of Charles, David, and three of their lawyers, according to the brothers’ attorneys.

In Bill’s case, there was often little need to rifle through his garbage cans: He was, as Vanity Fair‘s Bryan Burrough put it in a 1994 profile, “a man whose closet is free of skeletons in large part because they all seem to be turning somersaults in his living room.” Koch Industries distributed a 50-page file, titled “The Truth About Koch v. Koch Industries,” to reporters covering the legal drama. Some of the juiciest scuttlebutt concerned Bill’s stormy personal life (he would eventually father five children by four women), with some of the tawdriest moments playing out in courtrooms.

For example, in November 1995 Bill faced off against a former Ford model named Catherine de Castelbajac. He’d installed her in his seldom-used $2.5 million pied-á-terre in the apartment section of Boston’s Four Seasons, but wanted to evict her now that their romance had cooled. (De Castelbajac, the wife of a French nobleman when they began their affair, also became a target of Bill’s detectives. They uncovered her modest origins as, in Bill’s words, a “Santa Barbara surfing girl.”)

The 10-day trial over de Castelbajac’s housing arrangements revealed intimate details about the couple’s courtship (“She started kissing me quite passionately. I must admit I did not resist”), and a series of steamy transcontinental faxes were entered into evidence: “Hot Love From Your X-rated Protestant Princess,” de Castelbajac signed one of her messages. She referred to herself in a separate fax as a “wet orchid” who yearned for warm honey to be drizzled on her body. In another, she wrote: “My poor nerve endings are already hungry. You are creating such a wanton woman.”

Bill’s missives displayed the MIT-trained engineer’s geeky side: “I cannot describe how much I look forward to seeing you again,” he wrote. “It is beyond calculation by the largest computers.” In another fax, he jotted an equation to express his devotion, ending with a hand-drawn heart and the symbol for infinity. The trial revealed that as Bill wooed de Castelbajac, he had simultaneously juggled at least two other women.

In late November 1995, Bill won the court’s approval to evict the ex-model. Less than two weeks after the verdict was read, Bill’s newest love interest, 32-year-old Marie Beard, announced she was three months pregnant with his child—and that she was moving into his Palm Beach, Florida, mansion.

Meanwhile, an aura of Cold War-esque vigilance enveloped both Koch Industries and Oxbow, the energy company Bill founded after his ouster. “We were all paranoid because of the tactics that were in use,” said a former Koch executive. “There was a paranoia at some point that my secretary was a Bill Koch plant. You saw something at every turn.” Bill feared his brothers had tapped his phones and that Koch operatives had stolen documents from his offices. Paul Siu, an Oxbow executive and one of Bill’s close friends in the 1970s and 1980s, was canned after being suspected of spying for David and Charles, and he alleged that Bill had him tailed and bugged his phones. “After the proxy fight, he changed completely,” he told Vanity Fair. “Bill was in the first stage of Howard Hughes syndrome. Very paranoid.”

Spy games became a way of life for Bill, and he used them prodigiously during his 1992 bid for the America’s Cup. Though the race has long had a reputation for a certain amount of espionage, Bill took things to another level. “This is more than the gentlemanly sport it used to be,” he said at the time. “This is war.” He sent a 30-foot Bayliner speedboat with blackout curtains and a full complement of electronics gear out to cruise the waters around San Diego, shadowing rival boats as crew members of his racing syndicate, America3, pointed handheld lasers at their quarry to record speed and telemetry data. A deckhand, in a cheeky display of America3‘s surveillance powers, once trained his long-range binoculars on a group of rival sailors playing poker and radioed over to advise: “Keep the king. Discard the jack.”

Bill’s team was ultimately said to have spent more than $2 million on intelligence activities. He dispatched helicopters to track competitors and deployed divers (using rebreathers so the telltale bubbles wouldn’t arouse suspicion) to study the keels of rival yachts.

“That’s been his whole life—private investigators with his brothers and trying to get an edge in all kinds of nefarious ways,” said Gary Jobson, a member of the America3 crew who ended up having his own brush with Bill’s surveillance campaign. A decorated sailor who had won the America’s Cup aboard Ted Turner’s Courageous in 1977, Jobson had once been close with Bill, even convincing him to make a bid for the Cup. But when he quit the team in 1991, to join ESPN, Bill was incensed. “People don’t leave Bill Koch,” Jobson told me.

Bill, Jobson says, became convinced that he was leaking technical secrets to his opponents. “I had a bad vibe,” Jobson remembered. “I’d put the garbage out, and the garbage can would be on the other side of the driveway the next morning. And you would hear funny clicking noises when I talked on the phone.” Then Jobson arrived home one day to find a thick envelope on his doorstep. It contained a 150-page surveillance report from the detective agency Bill had hired to track him—leaked, he surmised, by a member of the America3 organization who had taken pity on him. “Holy Christ,” Jobson thought as he paged through the report, “these guys have been following me around for months.”

Over the course of the litigation with his brothers, Bill often stressed that he was not acting on emotion. He was merely a ruthless tactician plotting his way through a corporate conflict using every weapon (lawsuits, publicity, PIs) in his arsenal. Yet simultaneously, he expounded on grievances that went back to childhood—his absentee parents, poor self-image, bully of an older brother. “I almost wish,” he once said of Charles, “I would have started a fight with him 30 years ago.”

In August 1997, after more than a decade of legal skirmishing, Judge Sam Crow finally scheduled Bill and Frederick’s main lawsuit, which alleged that Koch Industries had concealed assets when it bought them and the other dissident shareholders out, for trial the following April.

The public relations war heated up as both sides traded accusations that the other had tried to unduly influence the jury pool through media interviews, television ads, and sly public opinion polls, including one testing the waters for a possible Senate run by Bill, who briefly considered challenging GOP Sen. Sam Brownback as a Democrat.

On a warm, clear afternoon in early April 1998, the four Koch brothers arrived at the Frank Carlson Federal Building in Topeka, the first time in years they had all been in the same place.

Led by the esteemed Chicago trial lawyer Fred Bartlit Jr., who a couple of years later would help George W. Bush litigate his way to the Oval Office, the plaintiffs’ legal entourage alone occupied three floors at the Ramada in downtown Topeka. By one estimate, Bill’s legal tab had surpassed $200,000 per week.

Working-class farmers, truck drivers, teachers, and retirees composed the bulk of the jury pool. “There’s no poor people in this case,” Bartlit told one potential juror. “Everybody’s rich. That’s just the way it is.”

Bartlit told the jury that the case “was about a man’s driving need for total control and total power.” It was about how “Charles Koch went above the law in this country and also how he went above the ordinary rules that we live by in dealing with our own family.”

Where Bill had flown in a shock troop of legal heavy hitters, Charles stayed the course with Bob Howard, the family’s longtime lawyer. A native Kansan, Howard wore a slightly rumpled suit, spoke in nasal tones, and had a mild, folksy manner. But his unassuming appearance belied a masterful legal tactician, and one who knew the Koch clan inside and out. He, too, portrayed the battle as a sibling dispute gone wrong. It was “a continuation of a bitter family fight that should have been settled in 1983 when we paid $1.1 billion for peace that has never come to Kansas.”

David was the first of the brothers to testify. Now the executive vice president of Koch Industries, he underwent three days of questioning, including on his twin’s firing. Why had David abstained from voting to kick his brother out of the company? His face flushed. “Well,” he began, “I have very strong feelings for my brother, and I wanted…” He trailed off, dabbing his eyes. “This is tough to talk about. Boy.” Bill had “acted very badly in the company,” he said, his voice breaking. “He’d done some terrible things.” He began to sob, his sorrow amplified through the rapt courtroom by the microphone clipped to his tie. Across the room, Charles lifted his glasses to dab a tear. Bill stared down at the table in front of him.

“Mr. Koch, do you want a recess?” the judge asked.

“I think I can get through it here.” David paused to collect himself. “I just didn’t want him to act this way. I knew he couldn’t work in the company anymore, so it was my desperate desire to try to maintain a relationship with him.”

Frederick took the stand on April 30. Shorter than his 6-foot-plus brothers, with the delicate features of his mother, the 64-year-old had sat silently through the proceedings—”so quiet and so almost like a nonfactor, like he didn’t want to be there,” remembered someone who attended the trial.

Frederick was active with a range of arts and cultural organizations, including the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and the Pierpont Morgan Library, and he was a regular at New York galas and fundraisers. But his penchant for staying out of the media had garnered him a reputation as a recluse, and even some people who had known him for years considered him an enigma. He thought little about dropping six figures at Sotheby’s, but would grow disdainful at his staff if they added too much postage to letters and packages. He spared no expense when it came to refurbishing his homes, but preferred taking the bus in New York and typically flew commercial.

“Today I’m largely involved in charitable activities,” Frederick told the court. He affected a British accent from the time he had spent in England overseeing the 10-year renovation of Sutton Place, where he had displayed his collection of 19th-century paintings. “It’s one of the most popular attractions within the environments of London. We’re completely sold out two years in advance.” His testimony was relatively brief. He was not interested in the oil business or the inner workings of the family company.

Bill was suffering from a cold when he began the first of seven grueling days of testimony. His voice hoarse, he portrayed his brother as a dictatorial chief executive whose management practices and anti-government philosophy had caused Koch Industries to run afoul of regulators. When Howard’s turn came, the attorney chiseled away at Bill’s testimony. He highlighted Bill’s efforts to extract money from Koch Industries, even if it meant breaking up the company his father had started by selling his holdings to a corporate raider such as T. Boone Pickens, or to Saudi investors.

“You wanted to continue to grow the company, or you wanted to put it up for grabs to see if you couldn’t get the highest possible dollar?” Howard probed.

“I had mixed feelings. My feelings were, on the one hand, I wanted to be purely an economic man, get the best economic deal; and on the other hand, I had a lot of emotional attachment to the company.”

“And in the competition between the two halves of yourself,” Howard asked, “what won out was, ‘Get the highest price,’ wasn’t it?”

“Oh, eventually, that’s what won out,” Bill acknowledged.

When Charles testified in late May, Bill looked away from the witness stand. During the proceedings, one person who attended the trial recalled, Bill “was like a caged animal. He was ready to attack.”

Charles may have been the CEO of a multinational corporation, but he was nevertheless uncomfortable with public speaking. “Work for Koch Industries,” he said quietly when asked to state his profession.

Charles testified haltingly, sometimes fumbling for words, but he ceded little ground. Early on, he upended the notion, advanced by Bartlit, that Fred Koch had taught his sons that litigation was the way to resolve tough disputes. “What I recall is the opposite,” Charles said. “My father had gone through a nightmare of litigation from 1929 to 1952. He said, ‘Out of those lawsuits, I finally settled for a million and a half dollars. The lawyers got a third, the government got a third, and I got a third, and I ended up with my business destroyed.’ So he said, ‘Never sue,’ those were his words.”

Later, as he recounted the family’s last Christmas together in 1979, when Bill’s tirade had brought their mother to tears, Charles appeared to stare directly at his brother as he spoke: “He accused her of being a bad mother, of not loving him, and that whatever problems he had were largely her fault.” Bill never looked up.

The long legal battle had taken a noticeable toll on each of the brothers, but perhaps none more so than Charles. The typically energetic CEO wasn’t sleeping well. He looked drawn and haggard. It was not just his company but his values that were under assault. “You could see a side of Charles that no one had ever seen before and no one will likely ever see again,” a former Koch executive said. “That trial—destroyed him is not the right word—it was as if he had aged 40 years.”

At 9:45 a.m. on June 19, when the jury sent a message to Judge Crow that they had reached a verdict, Charles and David were far from Topeka. David had returned to New York, where his wife, Julia, was expecting their first child. Charles was trying to occupy himself with work in Wichita. Frederick, too, was MIA; he had flown back to Europe. But Bill had remained in Topeka to anxiously await the verdict.

Judge Crow recessed the court and summoned the lawyers into his chambers. Bartlit emerged grim-faced. “They’re guilty of misrepresentation,” he told Bill, “but it’s not material.” The jurors, in other words, believed that Koch Industries might have concealed some facts during negotiations with the shareholders, but that these omissions had not significantly affected the sale price. There would be no damages.

When they learned they had prevailed, Charles and David wept with relief. Bill called the verdict a “moral victory.” But in reality, he was shattered.

In October 2000, in the midst of Bill’s messy divorce from his second wife, the long-running lawsuit reached the end of the road when the Supreme Court declined to hear Bill and Frederick’s last-ditch appeal. That summer, perhaps sensing that his case was doomed, Bill had initiated a cautious rapprochement with his brothers.

As negotiations quietly commenced, the most contentious disputes were over how the brothers would divide their father’s possessions. “We were dealing with large sums of money,” Bill recalled, “but the biggest thing we argued about was who was going to get what painting out of my father’s collection…It wasn’t the money, it was the emotional stake.” One of the final sticking points was the portrait of their father once displayed in the family living room. It now hangs in Charles’ office in Wichita.

The talks continued for 10 months. On May 23, 2001, a faint, salty breeze blew off the Atlantic as Charles and David arrived at Bill’s Palm Beach mansion, which evoked the plantation of some colonial viceroy and straddled a lush, four-acre property that stretched from the ocean to the Intracoastal Waterway. The home featured an open-roofed courtyard in the center, a 35,000-bottle wine cellar with a groin-vaulted ceiling crafted from 150-year-old bricks, and room after room of the kind of art rarely seen outside of the world’s finest museums—Dalí, Degas, Matisse, Homer, Remington. About two miles up the road, David owned the equally glorious, Addison Mizner-designed Villa el Sarmiento.

Bill had put together a small dinner party for the settlement signing. The agreement, in addition to dividing their father’s property and providing an undisclosed payout to Bill, included significant penalties if either side breached the peace accord.

The brothers had not shared a meal together in nearly 20 years. The lawyers, as always, were present as the three men awkwardly chatted about their families, about their lousy knees.

David still felt a powerful kinship with his twin, even though he had made his life hellish for years. Charles was cordial, but there was a limit to what he could forgive. Bill and he were no longer mortal enemies, but that was the extent of their detente. The brothers did manage a few laughs as they told old stories. Everyone chuckled at the memory of when Bill, always the hothead, had subbed in for David during a basketball game, only to get ejected within seconds for brawling.

“My dad used to say it takes two to fight,” Bill reflected after the settlement. “So many punches get thrown, you lose track of who threw the first one. No one in this whole event wears the white hat, and nobody wears the black hat.” He added, “There’s nothing more explosive or worse than blood and money.”

Not too long after the brothers formally ended their feud, Julia Koch picked up her son at his Palm Beach preschool. She noticed David Jr. with his arm around another child. This was his new best friend, David Jr. informed his mother. Out of all the other children at the preschool, the blond toddler had befriended his cousin, William Jr.

The Koch brothers led lives that were charmed with incredible privilege, but also plagued by immense struggle. Of the four, it was only Frederick who managed to retreat to his quiet existence on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Bill, for his part, unleashed his talent for legal warfare on fresh targets, embarking on a crusade against wine counterfeiters such as the scoundrels who sold him four bottles of Bordeaux that were said to have belonged to Thomas Jefferson. In a bizarre 2012 episode that bore echoes of his past misadventures in espionage, he was also accused of kidnapping and falsely imprisoning—on the Colorado ranch where he’d installed a replica of a Wild West ghost town—an employee of his company, Oxbow, who he believed was defrauding him. (Bill has denied the allegation; a lawsuit involving the incident is pending.)

Charles and David, too, pivoted to other fights, trading the controversy of their headline-grabbing family feud for notoriety as conservative kingmakers. Just as Charles and David had elevated their father’s midsize Midwestern oil company into an international behemoth, they have carried the family’s political torch into the 21st century in a way that Fred Koch would find hard to comprehend. Fred’s John Birch Society, where Charles began his political education, has been relegated to the fringe. But as Charles and David’s influence reached new heights during the Obama era, so too did the strain of thinking popular among Fred and his allies, who saw socialism (and its evil twin, communism) lurking behind government’s every move.

After mounting an unprecedented political effort in 2012, and earning little more than a reputation as rapacious villains for their trouble, the brothers and their allies have regrouped for another battle. The advocacy group they founded, Americans for Prosperity, is expected to dump $125 million into the upcoming midterm elections—and the Kochs are gearing up for an even bigger and more expensive bout in 2016. Like their father, it’s not in their DNA to back down from what they believe is a just fight. Decades have gone by, and peace has still never come to Kansas.

This article is excerpted from Sons of Wichita: How the Koch Brothers Became America’s Most Powerful and Private Dynasty (Grand Central).