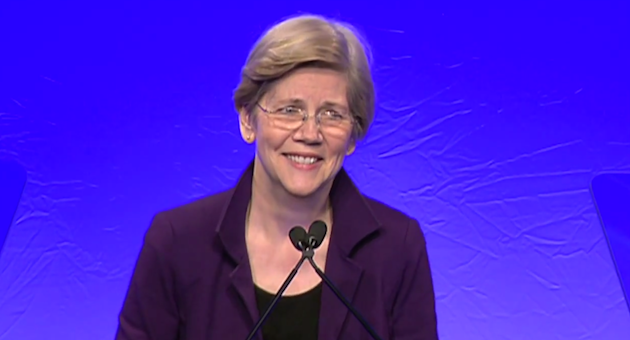

Xinhua/ZUMA

There is no love lost between Tim Geithner, the former US treasury secretary, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). Geithner and Warren memorably clashed during hearings over the $700 billion bank bailout (Warren at the time chaired Congress’ bailout watchdog panel), and many progressives believed that Geithner denied Warren her rightful place as the full-time director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

In his new book, Stress Test, Geithner denies blocking Warren and describes his relationship with the progressive favorite as “complicated.” He praises her “smart and innovative” ideas about consumer protection, which, over dinner in Washington with Warren, he discovers are “more market-oriented, incentive-based, and practical than her detractors realized.” In the same breath, though, Geithner jabs Warren for running her bailout oversight hearings “like made-for-YouTube inquisitions [rather] than serious inquiries.” (Geithner’s not the only one to point out Warren’s embrace of the viral video clip: Listen to BuzzFeed reporter John Stanton’s comments in this MSNBC roundtable.)

So why did the Obama administration pass over Warren to run the new bureau? Geithner writes, “There was a lot to be said for making Warren the first CFPB director, but one consideration trumped all others: The Senate leadership told the White House there was no chance she could be confirmed.” Warren’s eventual gig—a presidentially-appointed acting director charged with getting the new bureau up and running—was Geithner’s idea, he says:

[Chief of staff] Mark Patterson and I thought about options, and after a few discussions with Rahm, I proposed that we make Warren the acting director, with responsibility for building the new bureau, while we continued to look for alternative candidates. This would give her a chance to be the public face of consumer protection, which she was exceptionally good at, and the ability to recruit a team of people to the new bureau right away, which she wouldn’t have been allowed to do if she had been in confirmation limbo.

What stands out in Geithner’s retelling is the depth of President Obama’s admiration for Warren, and how much Obama agonized over what to do with Warren and the consumer bureau. The bureau was, after all, her idea. Here’s what Geithner writes:

The President was torn. Progressives were turning Warren into another whose-side-are-you-on litmus test. The head of the National Organization for Women publicly accused me of blocking Warren, calling me a classic Wall Street sexist. Valerie Jarrett, the President’s confidante from Chicago, was pushing hard for Warren, too, and she was worried I would stand in the way. At a meeting with Rahm and Valerie, I told the group that if the President wanted to appoint Warren to run the CFPB, I wouldn’t try to talk him out of it, but everyone in the room knew she had no chance of being confirmed. The president, who almost never called me at home, made an exception on this issue. It was really eating away at him. He had a huge amount of respect for Warren, but he didn’t want an endless confirmation fight, and he was hesitant to nominate someone so divisive that it would undermine the agency’s ability to get up and running, as well as its ability to build broader legitimacy beyond the left.

As soon as Warren got to the CFPB, she began trying to lure away Geithner’s own staffers. “She was unapologetic when my team finally confronted her about it,” he writes, “and you had to respect her determination to get things done.”