<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-39013411/stock-photo-plate-with-silverware-and-coins-isolated-on-white-background.html?src=T3LAaOqI1g1N1FkjON0DeA-1-94">Shawn Hempel</a>/Shutterstock

Update, Friday July 25: On Friday, the House passed Rep. Lynn Jenkins’ (R-Ks.) child tax credit legislation, which would expand the credit for upper-middle class American families. The bill received the support of 212 Republican and 25 Democrats.

On Friday, the House will vote on a Republican bill that ignores an expiring tax credit for millions of low-income families, while handing one to better-off Americans.

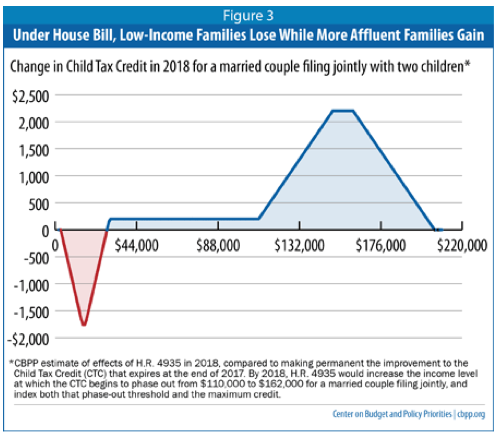

The bill, introduced by Rep. Lynn Jenkins (R-Ks.), changes the way the federal child tax credit works by raising the eligibility cap for married couples. At the same time, the legislation would allow a 2009 child tax credit increase for low-income families to expire at the end of 2017. Here’s how that would play out in the coming years. A married couple with two children that bring in $160,000 a year would get a new annual tax cut of $2,200, according to an analysis by the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). A single mother with two kids who makes $14,500 a year would lose $1,725 annually.

“The big winners would be the more-affluent families who would become newly eligible for the [child tax credit],” tax experts at the CBPP noted Tuesday. “The losers would be millions of low-income families who are doing exactly what policymakers often say they want these people to do—working, even at low-wage jobs.”

Here’s a look at how poor, middle-class, and wealthier Americans would be affected by the bill, via the CBPP:

The 2009 law that increased the child tax credit for poor families did so by lowering the income level required for a partial credit to $3,000 and reducing the annual income required for a full credit to $16,333. If it expires, 6 million children and roughly 400,000 veterans and military families would lose all or part of their child tax credit.

A spokesman for Jenkins explains that the reason the bill ends up extending the child tax credit to wealthier Americans is that it gets rid of the marriage penalty, which treats a married couple’s total income differently than the sum of two separate incomes. The way the child tax credit is currently structured, a single person making up to $75,000 is eligible for a full credit. But for a married couple filing jointly, full credit eligibility cuts off at $110,000 instead of at $150,000, the couple’s combined total income. Jenkins’ bill moves the full credit cut-off to $150,000. (As income increases above these thresholds, the child tax credit phases out slowly. Under Jenkins’ bill, for instance, a couple with two kids could still get the credit if they make up to $205,000.)

Jenkins’ office adds that the reason that the legislation does not extend the low-income child tax credit increase is that this provision doesn’t expire until the end of 2017, and future legislation can address it.

But a Democratic aide familiar with the bill says this justification is disingenuous, adding that if GOPers wanted to extend the low-income provision, they would. All 22 Republicans on the House ways and means committee voted for Jenkins’ bill, while all 15 Dems on the committee voted against it. “[Republicans] can say whatever they want,” the aide says. But “they are prioritizing making permanent [all the tax provisions] that they want to be permanent, and getting rid of everything else.” For instance, Republicans are already pushing to extend another tax measure that expires at the end of 2017 that is designed to help parents and students pay for college expenses.

The Democratic staffer adds that if Jenkins’ bill were to become law, and the low-income provision were left hanging on its own, it would be very difficult to “galvanize Congress into action” to pass a separate extension for the measure. “What carries it along is that it’s bundled together,” he says. Chuck Marr, one of the authors of the CBPP study, agrees that the most obvious way for the House to extend the low-income measure would be to include it in Jenkins’ bill.

Even if the legislation passes the House, the bill—which would cost the government $115 billion over ten years—has little chance in the Democratic-controlled Senate.