The ongoing outbreaks of Ebola in West Africa continue to devastate Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, and recently caused a national emergency in Nigeria—as of August 28, the Centers for Disease Control was putting the suspected and confirmed case count at 3,069, including 1,552 deaths. But in the last few days, with the virus entering Senegal and health workers discovering a fresh outbreak in Nigeria, global health groups such as the World Health Organization are getting increasingly strident with their concerns. On Sunday, WHO officials called Ebola’s arrival in Senegal “a top priority emergency.” On Tuesday, Joanne Liu, international president of the global health organization Doctors Without Borders, warned the United Nations that the world was “losing the battle to contain” the disease. “Leaders are failing to come to grips with this transnational threat,” she said.

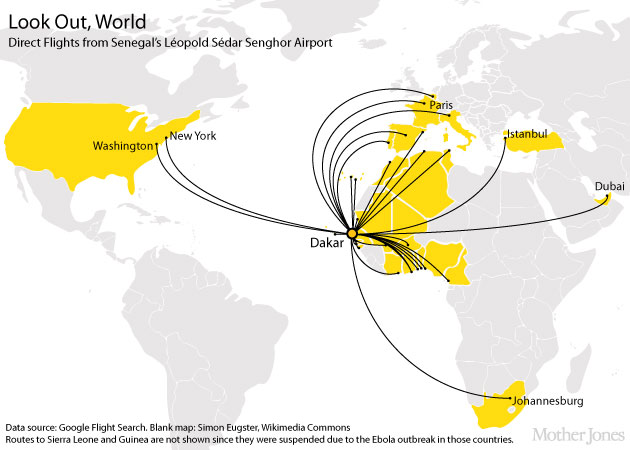

Senegal, with a population exceeding 13 million, is the fifth country afflicted in the crisis. But it’s an especially worrisome one, because Senegal is an international transit hub. More than 30 carriers fly through the Léopold Sédar Senghor airport in Dakar, on the continent’s westernmost point, ferrying passengers to and from destinations in 25 countries around the world. While most of the routes are regional, some connect with major airports in New York City, Paris, Istanbul, Dubai, and Johannesburg.

Compared to Senegal, the three countries that account for the vast majority of infections to date—Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea (see map below)—were isolated even before the outbreak: You could only fly directly to six destinations each from Liberia or Guinea, while carriers operating in Sierra Leone serviced ten routes. Despite the limited air traffic, the disease jumped borders when an American citizen flew from Liberia to Lagos, Nigeria, and become that country’s first reported infection, prompting some regional carriers to suspend flights to the three countries most affected.

At the end of August, British Airways and Air France also suspended flights to Liberia and Sierra Leone. At the time, British Airways’ service from London to those countries consisted of a single Liberia flight with a stopover in Sierra Leone, four times per week. Air France only had three flights weekly to Sierra Leone, shuttling between Paris and Freetown. “The flight risk is something to be taken fairly seriously,” says Parviez Hosseini, a mathematician and ecologist with the research group EcoHealth Alliance, who has analyzed countries’ risk of exposure based on flight data. “On the other hand, a lot of countries are taking it seriously.”

Ebola’s entry into Nigeria’s largest city in late July was a cause for fear in the global health community for the same reason that many people are concerned about the disease’s entrance into Senegal now. Nigeria, like Senegal, is internationally connected, with flights to and from numerous countries and a running influx of expatriates, mostly affiliated with the nation’s oil industry. A quick response by Nigerian authorities helped keep the case count in Lagos to a minimum—on Tuesday, Nigeria’s health ministry reported a total of just 17 confirmed cases nationwide since the outbreak began.

Yet following the discovery that a physician treating Nigeria’s first case had sought treatment for Ebola in Port Harcourt, an oil industry center where he was attended by numerous medical staff and members of his church, health workers put nearly 200 people there under surveillance. On Wednesday, WHO announced three confirmed cases in Port Harcourt, including the doctor. This new outbreak, the organization says, “has the potential to grow larger and spread faster than the one in Lagos.”

So far, the skies over Nigeria and Senegal remain crowded. But if Ebola’s arrival in Senegal and Port Harcourt goes unchecked, it will raise concerns about the disease hopping not just between countries, but between continents.