Chuck Myers/ZUMA Wire

Editor’s note: Sen. Bernie Sanders jumped into the crowded 2020 race. This story was published during his first presidential bid. Click here for more Sanders stories from Mother Jones’ archives.

Last month Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent socialist seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, repudiated a 1972 essay he wrote for the Vermont Freeman, an alternative newspaper, which included depictions of a rape fantasy from male and female perspectives. On Meet the Press, he dismissed the article as a “piece of fiction” exploring gender stereotypes—”something like Fifty Shades of Grey.”

Yet as the New York Times recently reported, during his years as a contributor to the Freeman in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Sanders often wrote about sexual norms, as he presented a broader critique of repressive cultural forces that he believed were driving many Americans literally insane. His early writings reflect a political worldview rooted in the fad psychology and anti-capitalist rhetoric of the era and infused with a libertarianesque critique of state power. Sanders feared that the erosion of individual freedom—via compulsory education, sexual repression, and, yes, fluoridated water—began at birth. And, he postulated, authoritarianism might even cause cancer.

Yet he insisted that individual acts of protests could turn things around—a belief that would give rise to his political career.

Sanders was initially drawn to Sigmund Freud and his theories as a high school student in Brooklyn. He then studied psychology at the University of Chicago and at the New School for Social Research in New York. And he worked at a mental institution in New York City before settling in Vermont for good in 1968. Like many lefties of his time, he was heavily influenced by the Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Reich, a disciple of Freud whose work drew a connection between sexual repression and fascism. When Paris student demonstrators took the street in that year, they held up copies of Reich’s book.

Reich’s most famous invention was a product called the “Orgone Box,” a sort of hyperbaric oxygen chamber for orgasms. The device was supposed to expose users to “orgastic” energy circulating in the air. Such exposure, Reich theorized, could cure various maladies, including cancer.

In a 1969 essay for the Freeman called “Cancer, Disease and Society,” Sanders, then 28, contended that conformity caused cancer by breaking down the human spirit and inflicting emotional trauma. He quoted liberally from Reich’s 1948 book, The Cancer Biopathy, which, he noted, was “very definite about the link between emotional and sexual health, and cancer,” and he walked readers through Reich’s theory about the consequences of suppressing “biosexual excitation.”

Then Sanders got to the point: “The above references, in no uncertain terms, state that you might very well be the cause of cancer.” He continued:

What do you think it really means when 3 doctors, after intense study, write that ‘of the 26 patients (who developed breast cancer) below 51 (years of age), one was sexually adjusted.’ It means, very bluntly, that the manner in which you bring up your daughter with regard to sexual attitudes may very well determine whether or not she will develop breast cancer, among other things.

And there was more:

How much guilt, nervousness have you imbued in your daughter with regard to sex? If she is 16, 3 years beyond puberty and the time which nature set forth for childbearing, and spent a night out with her boyfriend, what is your reaction? Do you take her to a psychiatrist because she is “maladjusted,” or a “prostitute,” or are you happy that she has found someone with whom she can share love? Are you concerned about HER happiness, or about your “reputation” in the community.

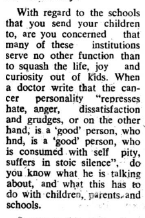

With regard to the schools that you send your children to, are you concerned that many of these institutions serve no other function than to squash the life, joy and curiosity out of kids. When a doctor writes that the cancer personality “represses hate, anger, dissatisfaction and grudges, or on the other hand, is a ‘good’ person, who is consumed with self pity, suffers in stoic silence”, do you know what he is talking about, and what this has to do with children, parents, and schools.

Theories about psychological causes of cancer were widespread in the mid-20th century, but never accepted within the scientific mainstream. According to the National Cancer Institute, psychological stress can have adverse health effects, but “the evidence that it can cause cancer is weak.” The American Cancer Society says that “[b]ased on what we know now about how cancer starts and grows, there’s no reason to believe that emotions can cause cancer or help it grow.” Reich died in prison in 1957 after ignoring an order by the Food and Drug Administration to stop advertising his Orgone Box as a cancer cure.

“These articles were written more than 40 years ago,” Sanders spokesman Michael Briggs said in an email to Mother Jones. “Like most people, Bernie’s views on many issues have changed over time.”

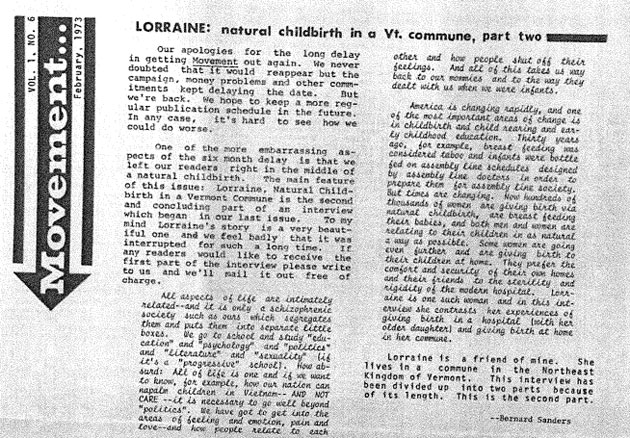

The big problem, Sanders noted in these early writings, was never-ending cultural oppression. The crisis, in his view, started with birth and continued through early childhood, the school years, and the daily grind of adulthood. In 1972, writing for a lefty newspaper he founded called Movement, Sanders published a lengthy interview with a friend who lived on a commune, on the subject of natural childbirth. The birth of the woman’s second child culminated in the sounding of a “hunting horn,” and the ritual eating of the placenta. (“Don’t all mammals eat the afterbirth?” Sanders asked.)

Sanders was trying to make a political point:

All aspects of life are intimately related—and it is only a schizophrenic society such as ours which segregates them and puts them into separate little boxes. We go to school and study ‘education’ and ‘psychology’ and ‘sexuality’ (if it’s a ‘progressive’ school). How absurd: all of life is one and if we want to know, for example, how our nation can napalm children in Vietnam—AND NOT CARE—it is necessary to go well beyond ‘politics.’ We have got to get into the areas of feeling and emotion, pain and love—and how people related to each other and how people shut off their feelings. And all of this takes us way back to our mommies and to the way they dealt with us when we were infants.

In a letter to the editor published in the Freeman in 1969, he called the growing disillusionment with public schooling “one of the most heartening signs in recent years,” and he remarked that “the basic function of the schools is [to] set up in children patterns of docility and conformity—patterns designed not to create independent and free adults, but adults who will obey orders, be ‘faithful’ uncomplaining employees, and ‘good’ citizens.” He took a similar tack in another essay, this one tongue in cheek, entitled “On Education.”

Treating children with kid gloves, he believed, was turning them into sexually repressed worker drones. In a 1969 essay in the Freeman, he wrote, “In Vermont, at a state beach, a mother is reprimanded by Authority for allowing her 6 month old daughter to go about without her diapers on. Now, if children go around naked, they are liable to see each others sexual organs, and maybe even touch them. Terrible thing! If we [raise] children up like this it will probably ruin the whole pornography business, not to mention the large segment of the general economy which makes its money by playing on peoples sexual frustrations.”

Some of his rants bordered on libertarian. He referred to water fluoridation, dairy regulations, and compulsory education as perhaps well-meaning infringements on individual choice that were contributing to the overall deterioration of the human condition. “It is obvious that in the name of ‘public safety’ the State is usurping the rights of free choice in many domains of life,” he wrote in a 1969 essay entitled “Reflections on a Dying Society.” Such regulations had a depressing effect on the soul, Sanders contended, citing a condition Freud referred to as the global “death instinct.”

His assessment of late-stage capitalism and American politics was grim. In another 1969 piece, he summed up modern life: “The years come and go, the suicide, nervous breakdown, cancer, sexual deadness, heart attack, alcoholism, sensibility at 50. Slow, death, fast, death. DEATH.”

But Sanders wasn’t fatalistic. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his response to the crushing corporate state was to rise up against it through the political system he decried. In 1971, two years after his first essays for the Freeman, he launched his first political campaign. He ran for Senate and lost, and then lost three more campaigns over the next four years.

Buried inside the darkness of his rhetoric was the optimistic belief that the status quo couldn’t be sustained. In 1969, he wrote:

Read the full essay. Vermont Freeman/Vermont State LibraryThe Revolution is coming and it is a very beautiful revolution. It is beautiful because, in its deepest sense, it is quiet, gentle, and all pervasive. It KNOWS. What is most important in this revolution will require no guns, no commandants, no screaming “leaders,” and no vicious publications accusing everyone else of being counter-revolutionary. The revolution comes when two strangers smile at each other, when a father refuses to send his child to school because schools destroy children, when a commune is started and people begin to trust each other, when a young man refuses to go to war, and when a girl pushes aside all that her mother has ‘taught’ her and accepts her boyfriend’s love.

The revolution comes when young people throughout the world take control of their own lives and when people everywhere begin to look each other in the eyes and say hello, without fear. This is the revolution, this is the strength, and with this behind us no politician or general will ever stop us. We shall win!

Twelve years later—after all those failed campaigns—he was elected mayor of Burlington. And his own revolution was under way.