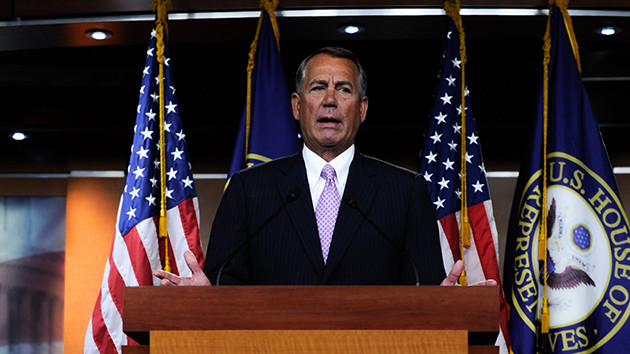

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP

John Boehner, a legislator who relishes regular order, has decided to orchestrate his own orderly departure from the House as speaker, rather than contend with a possible mutiny arising from a government shutdown that is materializing on Capitol Hill due to the battle over funding for Planned Parenthood. On Friday morning, Boehner announced he would be resigning within weeks (which might allow him the freedom to prevent his own party from causing another shutdown). This is not that great of a surprise. The surprise is that Boehner, an insider institutionalist leading a band of blow-it-up tea partiers, has lasted so long—that is, that he put up with the nonsense in his caucus and managed to survive. But he survived by yielding to the extreme forces in the GOP, which he and other party leaders had fueled and exploited to win control of Congress. Consequently, Boehner will exit the speakership with few positive accomplishments. He failed his own side by not stopping President Barack Obama on health care reform and other measures that conservatives despise, and he failed himself by not achieving any grand legislation that bears his mark. As speaker, he was more of an attendant than a legislator.

There was a specific month when Boehner’s dream of being a historic speaker evaporated: July 2011. His fellow Republicans had precipitated a crisis in Washington by refusing to accede to a routine move—raising the debt ceiling so the US government could pay its bills. Tea partiers were demanding deficit reduction and huge cuts in government spending in return for lifting the debt ceiling and threatening a financial crash. This led to a flurry of talks between the president and GOP leaders, and Obama saw this crisis as an opportunity. He initiated secret negotiations with Boehner. Why did they have to be undercover? To protect Boehner. The speaker could not persuade his own caucus that talking with the president to explore compromise had any value.

Through these conversations, Obama and Boehner reached what Washingtonians called a grand bargain. In essence, Obama would agree to cuts in government spending (including reductions in entitlement programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, but without any fundamental changes in these programs), and Boehner accepted increases in tax revenues that would be accomplished through reforming the tax code. At one private White House meeting of congressional leaders, Boehner declared, “I didn’t run for speaker just to have a fancy title.” He wanted to get something done. Something big.

Obama’s Democratic allies on the Hill—Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi—were wary of the deal. Eric Cantor, then the No. 2 Republican in the House, was also against it, believing House GOPers would never buy it. But Boehner wanted to try. White House aides began haggling with Boehner’s top staffers over the details. Obama was willing to take heat from his side to get this deal done and move on to other matters, such as how to improve the economy and create more jobs. Boehner, though, ended up bending to politics.

As his aides were hammering out the specifics with the White House, several of Boehner’s closest allies in the House Republican caucus came to his office. Word had spread that he was working on a deal with Obama that would lead to the end of tax breaks for the wealthy and an increase in tax revenues. As one of those lawmakers later recalled, “We told him, ‘You’re too far over the tips of your skis.'” These House members wanted him to pull back—and these were his friends. They were worried that if he proceeded, rebellious tea partiers would toss him out as speaker. Cantor and his allies, they warned Boehner, were whispering that Boehner had become a RINO—a “Republican in Name Only.”

About the same time, the conservative editorialists of the Wall Street Journal—who had been tipped off to the details under negotiation—published an editorial decrying Boehner and insinuating that he would be finished as speaker if he continued to pursue this deal.

After all this, Boehner turned tail. He backed out of the serious talks for the grand bargain. At one point, he even refused to return Obama’s call. Instead, he publicly proclaimed, “We are not close to an agreement.” But they had been. And he had been near to a sweeping piece of legislation that Boehner believed the nation needed. He just couldn’t make his own Republicans, who loathed any notion of compromise, act reasonably, and he was not willing to confront these extremists and risk his position as speaker. He might have been in charge of the House Republican caucus, but he was hardly a leader. He was a hostage.

In other episodes, Boehner couldn’t control his own caucus and saw his attempts to break legislative logjams—over budget, transportation, and farm bills—sabotaged by his GOP comrades. He couldn’t bring a comprehensive immigration bill to a vote. (He was caught on tape mocking his fellow Republicans for being afraid to take on this topic.) He managed to orchestrate dozens of meaningless votes to oppose Obamacare, but he couldn’t pull together a GOP alternative. Last week, he described his reality in these pathetic terms: “Garbage men get used to the smell of bad garbage. Prisoners learn how to become prisoners, all right?”

Boehner ascended to power due to the rise of tea party extremism within his party. He attempted to harness this political energy for his own purposes. In November 2009, he and other GOP leaders hosted an anti-Obamacare rally at the Capitol, where enraged protesters chanted, “Nazis, Nazis,” in reference to Democrats working to enact the Affordable Care Act. Boehner never tried to tamp down this sort of conservative anger. He did not tell the birthers to knock it off. He encouraged Obama hatred, allowing the Benghazistas to run free and filing a lawsuit against Obama to satisfy the Obama haters. Ultimately, he became a prisoner of these passions, and his speakership became mainly about one thing: preserving his own job. And that’s not much to leave behind.