J.W.Alker/DPA/ZUMA Press

When internet surveillance experts gather for a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee today, it will be one of the first public battles in the next stage of the war over the US government’s surveillance of its own citizens.

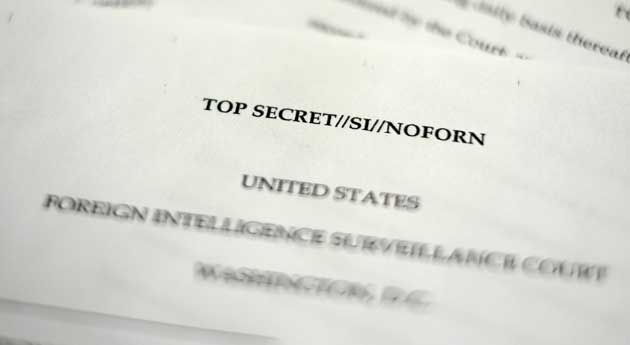

The hearing will focus on what’s called “702 surveillance”—a reference to the section of the 1978 law that authorizes the National Security Agency to collect the internet traffic of foreigners and that underpins two major NSA mass surveillance programs: one that allows the government to get data from internet companies, and the other for the “upstream collection” program that siphons directly from the internet’s basic infrastructure. Privacy and civil liberties groups say Section 702 is far too broad, enabling the NSA to “incidentally” collect intelligence on many American citizens as well. “We have every reason to believe that there’s a massive amount of Americans’ data being pulled in by Section 702,” says Elizabeth Goitein, the co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. The NSA also allows other federal agencies to search its section 702 database to help investigate crimes unrelated to terrorism, which Goitein calls “an end-run around the Fourth Amendment.”

Section 702 is due to expire at the end of 2017, and privacy advocates hope to force changes to the law that will narrow its scope and cut down on the amount of data the NSA collects from Americans.

Reformers have already had success in stopping one of the NSA’s bulk surveillance programs. A year ago, Congress passed the USA Freedom Act, which ended the NSA’s mass collection of phone metadata—records that included people’s phone numbers and the length of their calls. Privacy advocates hailed the end of that program as perhaps the biggest civil liberties victory of the post-9/11 era.

Privacy and civil liberty reformers had a strong argument against bulk metadata collection. Before the USA Freedom Act was passed, Richard Leon, a judge who sits on the federal court that approves surveillance programs, had already ruled that the phone records program was unconstitutional. The government also provided essentially no examples in which metadata collection had stopped any plots or attacks. In his ruling, Leon pointed to the “utter lack of evidence that a terrorist attack has ever been prevented because searching the NSA database was faster than other investigative tactics.”

The case against the 702 surveillance programs appears more complicated. For one, the government argues that Section 702 has been far more effective in fighting terrorism than the bulk metadata program. Officials said in 2013 that 702 surveillance had stopped more than 50 terrorist plots during its existence, and the White House panel that reviewed NSA programs in the wake of the Snowden leaks said Section 702 “does in fact play an important role in the nation’s effort to prevent terrorist attacks across the globe.” The section also specifically targets the communications of foreigners, who enjoy far fewer protections under US law.

Nonetheless, Goitein believes “a straight reauthorization would be tricky.” Civil liberties supporters in both chambers of Congress have raised concerns about Section 702 and have previously tried to end the authorization for other agencies to search the NSA’s data. Privacy advocates are also encouraged that public hearings are taking place more than 18 months before Section 702 expires. “We’ve never been able to start his early before,” says Amie Stepanovich, the US policy director of Access Now, a digital rights organization. “Starting this early actually gives a chance for Congress to consider the substantive reforms that are necessary.”