On February 25, when the GOP candidates gathered in Houston for a debate, nearly two weeks had passed since Justice Antonin Scalia’s sudden death, and the future of the Supreme Court was dominating the campaign. Vowing to appoint a “principled constitutionalist,” Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) slammed previous Republican presidents for nominating justices who proved to be insufficiently conservative. “The reality is, Democrats bat about 1,000,” he said. “Just about everyone they put on the court votes exactly as they want. Republicans have batted worse than 500. More than half of the people we put on the court have been a disaster.”

To Cruz and his allies, Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., appointed by George W. Bush, falls into the “disaster” category for his votes preserving the Affordable Care Act. So does Justice Anthony Kennedy, nominated by Ronald Reagan, for siding in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage. Even Scalia, whom Republican candidates have effusively praised for his “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution, occasionally surprised his ideological brethren by siding with the court’s liberal wing.

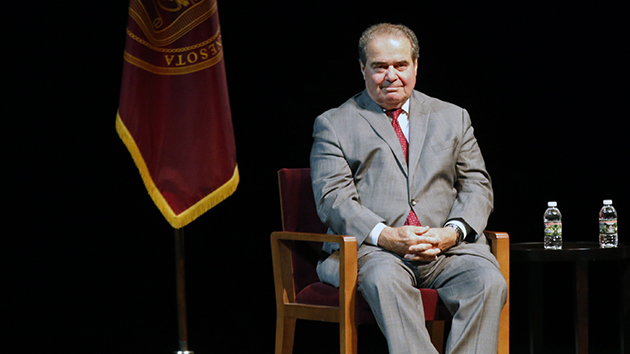

If a Republican (even Donald Trump) appoints the next Supreme Court justice, he won’t be looking for another Roberts, Kennedy, or even Scalia. Instead, he will seek another Samuel Alito—whose rulings on issues from abortion to unions to affirmative action never deviate from the conservative line.

“They’d like to have another justice who is perceived as having the intellect of Scalia, the writing skills of Scalia,” explains Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California-Irvine law school, who testified against Alito’s nomination. “But in terms of votes, they’d like to have Alito. He is in every case, in every area, a conservative. If you want to know his judicial philosophy, just look at the Republican Party platform.”

Predictability became the gold standard of a conservative Supreme Court justice, thanks in large part to David Souter, the George H.W. Bush appointee and “stealth liberal” whose nomination still haunts Republicans. Unlike Souter, who turned out to be a truly independent jurist, Alito “hasn’t changed a bit,” says the justice’s longtime friend Charles Cooper, a conservative Washington lawyer. “You can’t say that about too many people who have the kind of position he has.” Indeed, throughout his career, Alito has stayed true to his roots in the Reagan Justice Department, whose crusading lawyers laid the groundwork for the modern conservative legal movement that remade the nation’s federal courts. During his first decade on the Supreme Court, he has tilted the institution further to the right than any other justice since Clarence Thomas, who replaced legendary civil rights lawyer Thurgood Marshall 25 years ago.

“Justice Alito’s importance as an anchor of the conservative wing of the court will only grow in the wake of Justice Scalia’s passing,” notes David Lat, who founded the blog Above the Law and has argued before Alito on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals. But the fate of that conservative wing now also hangs in the balance: How Alito spends his next decade on the court—either cementing the conservative agenda or being relegated to a frustrated minority—may hinge on the next president.

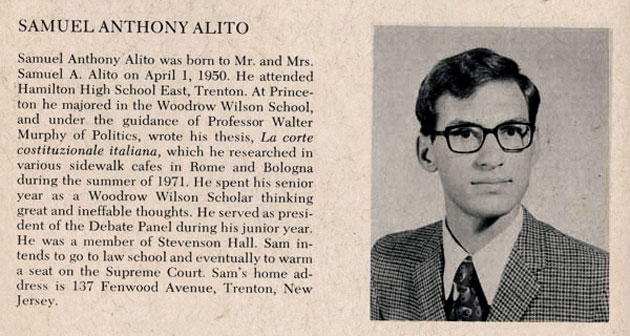

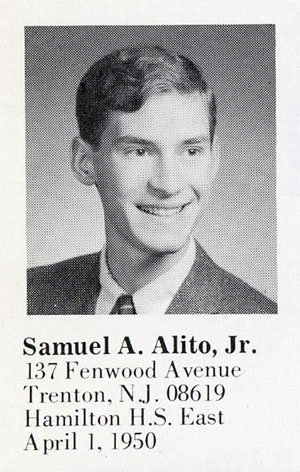

Alito’s career trajectory is not an arc but an unwavering line—one that he has followed since college, when as a Princeton senior in 1972 he declared in the yearbook his desire “eventually to warm a seat on the Supreme Court.”

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1950 to Italian American parents who were both teachers, Alito was raised in a home that was Catholic and traditional. His father, Samuel Alito Sr., eventually become executive director of the nonpartisan New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, where he was an expert in legislative redistricting. The younger Sam has often said that watching his pipe-smoking father draw New Jersey’s legislative maps by hand first piqued his interest in constitutional law.

Outside of his studies, baseball was young Sam’s main passion. A die-hard Phillies fan, he played second base in Little League and dreamed of a career in the majors—not as a player, but as the commissioner.

Even as a boy, Alito was a stickler for rules. “He liked structure and rigidity,” his middle school Latin teacher told the Washington Post in 2006. She posited that Alito enjoyed debate because “there were rules for when you could speak and how you spoke.”

For someone with a respect for tradition, authority, and order, the late 1960s would have been disorienting. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated months before Alito arrived at Princeton in 1968. Black neighborhoods were burning, including in nearby Trenton. Vietnam War protests raged and the civil rights and women’s movements were in full swing. Alito’s mother, Rose, told the Trentonian that many of her son’s peers got caught up in the counterculture, “but not Sam. He went to Princeton to study and that’s what he did.”

A member of Princeton’s last all-male class, Alito joined the ROTC and was dismayed to see it soon banned from campus because of anti-war sentiment. He found much of the social upheaval on campus distasteful. As he later recalled, he saw “some very smart people and very privileged people behaving irresponsibly.” After Princeton came Yale Law School, a brief stint in the Army, a clerkship on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, and a job in the appellate division of the US Attorney’s Office in New Jersey. In 1981, Alito went to work for Rex Lee, the Reagan administration’s solicitor general (whose son Mike would later clerk for Alito and ultimately win a Senate seat as a tea party conservative).

Those early years in the Reagan Justice Department were heady for conservatives, who had felt persecuted for their views during the ’60s and ’70s and were now bent on restoring order to the nation. The department was an incubator for lawyers who would ultimately become the foot soldiers of the Federalist Society, a legal group founded in 1982 by conservative students with the aid of Antonin Scalia, legal scholar Robert Bork, and Edwin Meese, a Reagan confidant and eventual attorney general. Its mission included turning the nation’s federal courts back to a focus on the original text of the Constitution and away from the expansive view of civil rights favored by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren. The society prioritized grooming conservative lawyers who would go on to inhabit important posts in government and the judiciary. Alito was among them.

Alito has described himself as a “secret conservative” during his early years in Washington. John Garvey, the president of the Catholic University of America who worked with Alito in the solicitor general’s office, says, “In all my time of serving with him, I had no idea what his politics were, and we had lunch every day.” The sentiment wasn’t unique to Garvey. One day Alito ran into Charles Fried, who had recently taken over from Lee as solicitor general, at a Federalist Society meeting. “They used to have these lunches at a Chinese restaurant,” Alito told the American Spectator in 2014. “Charles was there and he came up to me and said, ‘Oh, what a surprise to see you here. This is like meeting a friend at a bordello.'”

Charles Cooper, who had recently been tapped to lead the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, offered Alito a political appointment as his deputy in 1985. Alito trumpeted his conservative fealty in a letter outlining his commitment to the administration’s political goals. He pulled out all the stops describing William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater as key influences. He proudly cited his work defending President Reagan’s agenda, particularly in Supreme Court cases in which he had argued that “racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed and that the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion.” To underscore his commitment to conservatism, Alito noted his membership in the Federalist Society and a group called Concerned Alumni of Princeton, formed by alums who were outraged by the admission of women into the university. He got the job.

Alito pleased the administration enough that near the end of Reagan’s term he was appointed as the US attorney for New Jersey, where he went on to prosecute alleged mob bosses. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush tapped him to serve on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals (where he had previously clerked).

On the 3rd Circuit, Alito staked out the staunch views that would come to mark him as far to the right of even his fellow Republican appointees on the federal bench. A classic example was his dissent in Doe v. Groody, a case in which a Pennsylvania drug task force had raided the home of a suspected meth dealer. Their warrant authorized only a search of the suspect, but the cops strip-searched the man’s wife and 10-year-old daughter. The wife sued, arguing that the police had violated the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable and warrantless searches. The 3rd Circuit agreed—the lone holdout was Alito, who saw nothing wrong with the cops’ decision.

It’s not like the majority opinion was written by a bleeding-heart Jimmy Carter appointee. Its author was Michael Chertoff, a former federal prosecutor whom George W. Bush would later appoint to head the Department of Homeland Security. Chertoff, a Federalist Society member himself, sharply critiqued Alito’s legal rationale in his decision, saying it would turn judges who approve warrants into “little more than the cliché ‘rubber stamp.'”

According to a 2005 analysis by legal scholar (and eventual Obama administration official) Cass Sunstein, Alito’s 3rd Circuit dissents strongly reflected a “conservative’s conservative.” Alito’s record was especially consistent in civil rights cases: He voted against people alleging race, age, gender, and disability discrimination in 85 percent of divided cases, according to People for the American Way, a liberal advocacy group. He was also the lone judge to side in favor of striking down a federal ban on the possession of machine guns. But perhaps his most controversial ruling came in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a 1991 case challenging a Pennsylvania anti-abortion law that imposed strict waiting periods for women seeking abortions. The 3rd Circuit upheld the law, except for a provision requiring married women to alert their husbands before seeking an abortion.

Alito dissented, arguing that the spousal notification provision should also be upheld. He curtly dismissed concerns that such a measure could expose women to domestic violence. “Whether the legislature’s approach represents sound public policy is not for us to decide,” he wrote. He claimed earlier Supreme Court rulings authored by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor supported his reading of the law.

In fact, O’Connor soundly rejected his argument when the case went to the Supreme Court in 1992. She wrote the majority opinion with two colleagues in a 5-4 decision jettisoning the notification provision. “Women,” they ruled, “do not lose their constitutionally protected liberty when they marry.”

Thirteen years later, O’Connor announced she was retiring to care for her ailing husband. It was her seat that Alito would come to warm when he was confirmed in January 2006. President George W. Bush had nominated John Roberts Jr. to replace her, but when Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, Bush tapped Roberts for chief justice instead. Conservatives torpedoed Bush’s nomination of White House counsel Harriet Miers for associate justice, opening the door for Alito.

Beyond conservative legal circles, Alito was mostly unknown. Describing him as “painfully shy” in his book Courage and Consequence, Karl Rove recalled a meeting with Alito and the officials who would be vetting him for the Supreme Court slot: “The poor man was shaking when he came into the dining room at the vice president’s residence. There was nothing we could do to put him at ease. He just sat there twitching, sweating, and visibly distraught. But boy, was he smart.”

Quiet and bookish, Alito brought none of the law partner panache that had helped Roberts ease through the confirmation process a few months earlier. Once liberals and civil libertarians reviewed Alito’s record, they recoiled. Until then, the American Civil Liberties Union had only twice in its 86-year history opposed a Supreme Court nomination, that of Rehnquist, who had once defended the “separate but equal” doctrine of race relations, and that of Robert Bork, whose nomination by Reagan was scuttled in 1987 over concerns about his conservative extremism. The organization opposed Alito largely because of his views on presidential power, which he seemed to regard as virtually limitless.

Democrats grilled Alito during lengthy confirmation hearings, especially about his membership in the Concerned Alumni of Princeton. The group had published a magazine, Prospect, which promoted the view that Princeton was becoming too liberal and straying from its Christian character. The publication referred to gay students as “campus lispers” and to feminists as “frumps and freaks,” and it argued that the school was lowering its standards to admit minority applicants, according to a Princeton alum who submitted testimony during Alito’s confirmation hearings. Two years before Alito touted his membership in the group to the Reagan administration, Prospect published an article dubbed “In Defense of Elitism,” which declared, “Everywhere one turns blacks and Hispanics are demanding jobs simply because they’re black and Hispanic, the physically handicapped are trying to gain equal representation in professional sports, and homosexuals are demanding that government vouchsafe them the right to bear children.”

A search of Concerned Alumni documents, ordered by the late Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.), never turned up any evidence that Alito had done more than join the group. But Alito’s grilling over his membership grew so heated that, at one point, Alito’s wife, Martha-Ann, fled the hearing room in tears.

Yet in sharp contrast to the quivering judge Rove claimed to have met weeks earlier, Alito faced down his questioners with steely resolve. He told the Senate Judiciary Committee that he was unaware of and opposed to the group’s sexist and racist positions. “I disavow them, I deplore them. They represent things I have always stood against,” he said. He speculated that he had only joined the group in response to the ROTC’s 1970 ejection from campus.

Alito’s deflection was masterful. Writing in The New Yorker, Janet Malcolm observed that during the hearing “he was like a chauffeur who speaks only when spoken to…His language was ordinary and wooden…It seemed scarcely believable that, in his 15 years on the federal bench, this innocuous man had consistently ruled against other harmless individuals in favor of powerful institutions, and that these rulings were sometimes so far out of the mainstream consensus that other conservatives on the court were moved to protest their extremity.”

Alito was confirmed 58-to-42. Among those who opposed him was Sen. Barack Obama, who gave a floor speech saying he was “deeply troubled” by Alito’s record. “I have found that in almost every case, he consistently sides on behalf of the powerful against the powerless, on behalf of a strong government or corporation against upholding Americans’ individual rights,” Obama said. “In sum, I’ve seen an extraordinarily consistent attitude on the part of Judge Alito that does not uphold, I believe, the traditional role of the Supreme Court as a bastion of equality and justice for United States citizens.”

Alito’s impact on the court was immediate and profound. Within months, he voted with the majority in a 5-4 decision in Gonzales v. Carhart, upholding the federal “partial birth” abortion ban, even though the court had struck down a virtually identical state law seven years earlier. The decision prompted an angry dissent from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who read her opinion from the bench to emphasize her displeasure. She observed that the only difference between the first decision and the second was that the court was “differently composed,” alluding to the shift from O’Connor to Alito.

Alito also tipped the scales on campaign finance. In 2003, O’Connor had cast the deciding vote upholding key parts of the McCain-Feingold Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, which banned corporations from paying for campaign ads with funds from their treasuries. But in 2010, Alito voted with the majority in Citizens United to obliterate that provision and allow unlimited corporate money into the political system.

Alito didn’t write the Citizens United decision, but many court-watchers credit him with influencing the outcome. Alito is not the most outspoken justice, but he can be a devastating interrogator. “He really knows how to identify the weakest point in a lawyer’s position and ask a question that exposes how weak it is,” observes Harvard law professor Mark Tushnet. This skill was on display during the oral arguments in Citizens United, when Alito posed a question that “may have changed the trajectory of the case,” notes University of California law professor Rick Hasen in his new book, Plutocrats United.

The case involved a nonprofit group—Citizens United—that had produced a film critical of Hillary Clinton and planned to release it on television while she was running for president in 2008. The McCain-Feingold law barred such political content from broadcast within 30 days of a primary election. Citizens United, believing the film would be blocked, preemptively sued the Federal Election Commission, arguing that the prohibition was an unconstitutional restriction on free speech. The case might have focused on narrow legal interpretations of the statute—until Alito zeroed in on a critical element. If the court accepted the government’s argument, he asked, couldn’t Congress ban any book that argued for or against a candidate? Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart, representing the government, offered a muddled answer that suggested it could.

“That’s pretty incredible,” Alito replied. “The government’s position is that the First Amendment allows the banning of a book if it’s published by a corporation?”

Suddenly the specter of governmental censorship trumped concerns about corporate money in politics. Alito, says conservative lawyer James Bopp, who spearheaded Citizens United, “won’t let people off the hook if they won’t give him a candid answer. He’ll pursue it. I think that has helped the court to decide cases—because he goes to the heart of it.”

Little seems to raise Alito’s blood pressure in the courtroom. But every now and then, a case strikes a nerve. One was 2011’s Snyder v. Phelps, over whether the Westboro Baptist Church could continue its two-decade practice of picketing military funerals with “God Hates Fags” signs and other virulent placards. In 2006, the church protested the funeral of Matthew Snyder, a young Marine killed in Iraq. His father sued, and a jury awarded him millions of dollars in damages for emotional distress and other claims. An appeals court threw out the verdict on First Amendment grounds. In 2011, the Supreme Court agreed—except for Alito.

In one of his most passionate dissents, Alito wrote that “in order to have a society in which public issues can be openly and vigorously debated, it is not necessary to allow the brutalization of innocent victims.”

By contrast, the empathy Alito manifested for Snyder, a white, Catholic father, is rarely on display for people whose experience he doesn’t share: minorities, criminal defendants, women in need of contraception. When Alito sides with plaintiffs in discrimination cases, they most often are either white or facing religious discrimination. He’s voted with white firefighters denied promotion, largely overlooking the plight of their black colleagues who’d faced decades of discrimination. One of the few times that he’s sympathized with someone behind bars came this year when he wrote an 11-page dissent to the court’s refusal to take up the case of a Jewish North Carolina prisoner denied permission to hold a religious study group in prison.

His inability to acknowledge the realities for women facing discrimination in the workplace has provoked exasperation from Justice Ginsburg. “There have been some pretty significant decisions that he has written which had a terrible impact on women,” says Emily Martin, general counsel for the National Women’s Law Center. She points to his 2007 majority opinion in Ledbetter v. Goodyear, which made it harder for women to bring equal-pay lawsuits. (As his first act in office, President Obama signed a bill that rolled back the ruling.) Alito also authored the 2014 Hobby Lobby decision, which protected the religious freedom rights of a for-profit corporation to deny women coverage for contraception through its insurance plan.

In some cases, Alito can come across as flat-out insensitive, particularly with regard to criminal defendants. Last term, the court considered Glossip v. Gross, a case involving a group of Oklahoma death row inmates who challenged their pending lethal injections with the controversial drug midazolam, which had been implicated in several botched executions over the previous two years. Alito wrote the majority opinion, rejecting Glossip’s assertion that use of the drug would result in cruel and unusual punishment. Because the court has held that capital punishment is constitutional, Alito said, states must have a way to carry it out, even if it causes pain: “After all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune. Holding that the Eighth Amendment demands the elimination of essentially all risk of pain would effectively outlaw the death penalty altogether.”

Alito had more concern about the suffering of abused animals. In 2010, he was the lone dissenter in United States v. Stevens, in which the court struck down a federal law banning “crush videos” that showed intense animal cruelty, such as kittens being crushed by high heels. The court found that the videos, however dreadful, were protected under the First Amendment, even though the animal cruelty they recorded was typically illegal. “The animals used in crush videos are living creatures that experience excruciating pain,” Alito wrote.

The case clearly struck a personal chord. A dog lover, Alito sometimes brought his now-departed springer spaniel, Zeus, to work with him, in part because the dog was suffering from separation anxiety. He once joked to law students that his outlier dissent in Stevens was the result of allowing Zeus to decide.

Alito’s reputation for being cool and dismissive owes in part to his body language. Personal acquaintances describe him as unfailingly polite and respectful, but he’s known for rolling his eyes and shaking his head in disapproval in public forums and when hearing cases. The most famous occasion came at Obama’s 2010 State of the Union address, when he appeared to mouth “not true” in response to the president’s critique of the Citizens United ruling. Court-watchers have also called out Alito for expressing disdain for the opinions of his female colleagues. He once rolled his eyes as Justice Ginsburg read her dissents in a pair of employment discrimination cases.

“I think Sam has a lousy poker face,” says his old friend Charles Cooper. “But it’s better than it was. Knowing him the way I do, I know that the last thing he would want to do ever is give offense to a colleague, or to anybody. You’ve got to be close to him to appreciate that nature of his personality…There’s just not a mean bone in his body.”

He may have a bad poker face, but Alito excels at the inside game. What makes him such a force on the court is his ability to identify and exploit holes in long-established precedent to achieve conservative goals.

Consider how he set the stage for a case argued before the court in January, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, which could have dramatically weakened public-employee unions. In recent years, the anti-union National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation has initiated a pair of cases, Knox v. seiu (2012) and Harris v. Quinn (2014), to further the conservative mission of defunding unions, a big source of Democratic Party campaign contributions. Those cases targeted the decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, a 1977 opinion in which the Supreme Court ruled that public-sector unions could charge nonmembers mandatory fees for the cost of representing them in collective bargaining because those nonmembers would benefit from the unions’ work. Both cases were decided in favor of the union foes, with Alito penning the majority decisions. The facts of neither Knox nor Harris supported driving a stake through Abood. But in Knox, Alito strayed beyond the questions at issue to suggest that Abood was unconstitutional—judicial activism vigorously opposed in an opinion by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

In Harris, Alito slyly offered union opponents a road map to a more expansive ruling. He suggested Abood violated the free-speech rights of public employees, who were forced to support unions whose political positions they didn’t necessarily agree with. And now there is Friedrichs, a case tailored to the argument Alito had outlined, and designed to deprive public-sector unions of millions of dollars in fees and weaken their bargaining power. The case looked headed to be headed for a 5-4 decision against the unions—until the unexpected death of Justice Scalia in February. In March, the eight-member court deadlocked 4-4 and issued a one-sentence decision upholding a lower court ruling siding with the unions.

Perhaps more telling than his judicial activism is his willingness to appear at donor events for conservative groups, including the Federalist Society, where he’s been a regular guest at conferences and galas. In 2008, he headlined an event for the American Spectator, a conservative magazine that published attacks on Clarence Thomas accuser Anita Hill and investigated Bill Clinton’s sex life. In 2010, he headlined an event for the Manhattan Institute, chaired by billionaire hedge fund director and GOP activist Paul Singer. He once appeared at a fundraiser for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, a conservative student leadership group that gave rise to James O’Keefe, the activist known for his undercover-video sting operations.

Alito’s support for these groups has fueled the perception that he’s the court’s most ideological justice. (Chief Justice Roberts, for instance, doesn’t speak at such partisan events.) Even Alito’s former boss Charles Fried has said Alito seems too politically driven. “The quality of his work is excellent,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “He is not a wiseguy. He doesn’t demean those who disagree with him. And you don’t get pompous sloganeering from him. But I’m sorry that on the agenda items, he’s been quite predictable. There’s a real sense of an agenda with this court, and he’s been part of that.”

Scalia, though known as a hardliner, sometimes broke with his conservative colleagues. So has Thomas. Most of the liberal justices have occasionally crossed the aisle. But, says Alito’s friend and admirer Akhil Reed Amar, a liberal Yale Law School professor, “There’s not a single important, politically charged case that I know of in 10 years where [Alito] was the fifth vote with the four liberals.”

And it’s telling that while Alito’s allegiance to Republican principles hasn’t wavered, his stance on questions of executive power has shifted markedly between the Bush and Obama administrations. As a young Justice Department lawyer, Alito subscribed to the “unitary executive” theory, which argues for near-total deference to the president, and he championed the use of presidential signing statements, supplements attached to legislation that can affect the way the law is carried out. The George W. Bush administration used such statements extensively to effectively nullify sections of legislation with which it disagreed.

When he first joined the court, Alito hewed to that view of robust executive power. In 2006, when the court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld that the Pentagon’s military commissions at Guantanamo Bay were illegal, Alito dissented. Two years later, in Boumediene v. Bush, the court ruled that Guantanamo prisoners had the right to challenge their detention in federal court. Again, Alito disagreed, voting to support the president who had nominated him.

But since Obama has taken office, Alito has routinely sided against the White House, including in two challenges to the Affordable Care Act. “Over the past 10 years, I have been struck by assertions of executive power that extend far beyond anything I had ever imagined,” he griped to a crowd of Federalist Society members in September, referring to the Obama administration’s actions in cases involving immigration and regulating greenhouse gases, according to an attendee of the event.

“It’s just hard to escape the conclusion that there’s a political filter here,” says American Enterprise Institute scholar Norman Ornstein.

At 66, Alito is one of the court’s younger justices. Anthony Kennedy turns 80 this summer; Stephen Breyer is 77; Ginsburg is 83. The next president is likely to appoint several new justices—possibly even filling Scalia’s seat if Republicans succeed in blocking Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland. “Let me tell you,” Donald Trump said during a debate in March, emphasizing the stakes, “if we lose this election, you’re going to have three, four, or maybe even five justices, and this country will never, ever recover. It will take centuries to recover.”

Already, Scalia’s death has touched off a shift at the court, which after a decade of archconservatism is suddenly experiencing something of a liberal resurgence. The court’s left-leaning wing is asserting itself, with the three female justices dominating oral arguments in a recent case over a Texas law that has wiped out most of the state’s abortion clinics. In March, the court threw out the murder conviction of a death row inmate because of prosecutorial misconduct. There’s some evidence that the corporate interests and conservative groups that have pushed cases to the high court, hoping to take advantage of its friendly makeup, are pulling back. Even the National Rifle Association recently dropped a challenge to New York’s post-Sandy Hook gun control law, fearing a negative outcome without Scalia.

With the court now split 4-to-4 between its liberal and conservative wings, the justices could wind up deadlocked over high-stakes cases that are already on the docket. This includes the Texas abortion case, as well as those involving immigration and redistricting. If that happens, the last ruling—from the lower court—will be affirmed. This means many pending blockbuster cases conservatives once considered slam dunks no longer are.

To beat back the liberal tide, Alito has joined forces with Thomas, the court’s other remaining hardcore conservative. Within weeks of Scalia’s death, the pair issued unusual joint dissents to decisions over whether to take certain cases, while the other Republican appointees, Roberts and Kennedy, sided with their liberal colleagues.

Alito’s legacy—whether it will be leading a conservative renaissance on the court or issuing acerbic dissents—depends on who next occupies the Oval Office. A Democratic victory would leave Alito in a far-right coalition of two. But if a Republican ascends to the White House, Alito will be the center of gravity of a conservative voting bloc for many years to come, with the power to roll back decades of advances in civil and reproductive rights and to further dismantle the regulatory state. In this scenario, notes Ornstein, the court will not only get more Alitos; it will probably get “people who make Alito look moderate.”