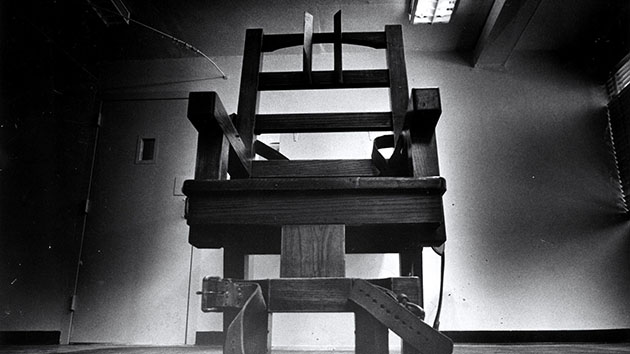

Dave Nakayama/Flickr

On Election Day, California voters will choose between two competing ballot measures: Proposition 62, which would abolish the death penalty in the state, and Prop. 66, which would speed up the execution process. If both pass, the one with the most votes will supersede the other. If neither passes, California’s death penalty system will remain unchanged.

A recent poll indicates that Prop. 66 is on track to be approved, but Prop. 62 is facing some stiff opposition—including from some death row inmates.

Over the summer, a Chicago-based nonprofit called the Campaign to End the Death Penalty sent a survey to all 749 death row inmates in California. The survey asked them to answer six questions about their feelings on the death penalty, Prop. 62, and whether the challenge of Prop. 66 should affect how people vote on Prop. 62. All but one respondent expressed opposition to the death penalty, yet more opposed Prop. 62 than supported it. Of the 46 inmates who had responded as of last Friday, 22 opposed the measure, 17 supported it, and 7 took no position. (No one—including the respondent who supported the death penalty—supported Prop. 66.)

Lilly Hughes, director of the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, said inmates’ opposition to Prop. 62 has to do with the way it’s written. The Justice That Works Act—the legislative title for Prop. 62—would make life without parole the maximum sentence for murder and be retroactively applied to all inmates currently on death row. “People feel that it’s just a death sentence with a different name,” Hughes told me. Kenneth Hartman—who has served 37 years of a life-without-parole sentence in California State Prison in Los Angeles County—echoed that sentiment during a phone call. Hartman heads the Other Death Penalty Project, an inmate-run nonprofit that advocates against life-without-parole sentences and opposes Prop. 62. “Fundamentally, we believe that life without parole is just another method of execution,” he told me. “You die in prison. It just takes a longer, slower time to do it.”

Many inmates also do not want to give up the state-sponsored resources guaranteed them to fight their convictions as long as they’re facing execution, notes Kent Scheidegger, legal director at the conservative Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. Only inmates on death row are guaranteed an attorney for their appeals—and a review of their trial process by a federal court that considers factors like attorney incompetence, potential procedural errors, and racial bias. Death row inmates are also granted more funding for their attorneys to investigate their cases and retain expert witnesses. “If the inmates’ primary focus is getting the conviction overturned, then they are better off, in a sense, being sentenced to death,” Scheidegger says.

The Justice That Works Act would also require all inmates serving life without parole for murder to work and would raise the percentage of their earnings that must be paid toward restitution for their victim’s families from 50 to 60 percent. It would allow the state to continue taking money out of the funds sent to them by their friends and family as well. Some survey respondents who opposed the act said 60 percent was too high, that their families shouldn’t have to pay, or that they wanted to decide for themselves what to do with their time in prison—including not work.

California has more people on death row than any other state but hasn’t executed anyone since 2006, when the state Supreme Court ruled the state’s lethal injection method unconstitutional and instituted a moratorium on executions. Only 13 people have been executed since 1978, when capital punishment was restored after the state Supreme Court had ruled it unconstitutional in 1972. The state Supreme Court also currently hears all death penalty appeals—a process that has often taken as long as 10 to 15 years—so many condemned inmates sit in prison for years on end without an execution date. An analysis by the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office argues that Prop. 62 would save California taxpayers $150 million annually within a few years, partly because the state wouldn’t have to keep paying for death penalty legal proceedings.

Back in 2012, the last time there was a ballot measure seeking to abolish the death penalty, the Campaign to End the Death Penalty sent a similar survey to 100 death row inmates in the state. The vast majority of the 35 respondents opposed the measure, Hughes said, for reasons similar to those expressed this time around. She thinks the amount of inmate support for Prop. 62 has to do with the fact that, this time, there’s also a competing measure that would put inmates on the fast track to execution. Prop. 66 aims to shorten the death penalty appeals process by assigning condemned inmates’ initial challenges to their convictions to state trial courts, creating a timetable for reviewing capital cases, and requiring appointed attorneys to work on death penalty cases.

The Campaign to End the Death Penalty does not have a public stance on Prop. 62 or Prop. 66. Officially, however, the campaign is opposed to both the death penalty and to life without parole. The point of the survey, Hughes says, was not to sway voters one way or another but to bring the voices of death row inmates into the public debate. One respondent wanted voters to know that “both [the] death penalty and life without [parole] are cruel forms of punishment and life without may be worse.” Another, who supported Prop 62., wanted the public to remember that innocent people have been executed. A third advised simply, “Vote your conscience.”

You can read death row inmates’ response to the survey here.