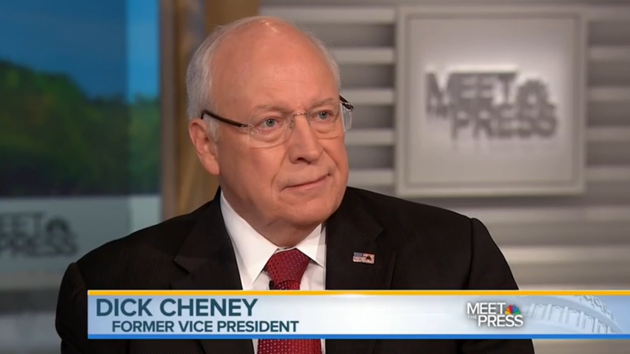

Jenna Vonhofe/Casper Star-Tribune/AP

When Liz Cheney returned to her ancestral home state of Wyoming in 2012, she expected to be greeted as a liberator. She moved into a house in Jackson Hole, not far from her parents, Dick and Lynne; she bought a horse for her 13-year-old daughter; and she began laying the foundation for a Senate run.

But in the rush to jump-start her political career, Cheney neglected to inform the man she was angling to replace—Mike Enzi, her father’s fly-fishing buddy and the state’s senior senator. Enzi had been planning to retire after 2014, and had Cheney asked for his blessing, he might have stepped aside. When she surprised him by jumping into the race, he decided his retirement could wait.

Things descended from there. A local newspaper revealed that Cheney had obtained a Wyoming fishing license without fulfilling the residency requirements. Robocalls alleged that she supported same-sex marriage, prompting her to proclaim that she did not, and provoking her sister, Mary, who is gay, to denounce her on Facebook and cancel their Christmas plans. Cheney found herself in the crosshairs of a bitter insurgency with few allies on her side. She dropped out of the race before the primary.

Lesson learned. In November, bolstered by a few mended fences and backed by family friends such as Karl Rove and Donald Rumsfeld, Cheney easily won her race to succeed retiring Republican Rep. Cynthia Lummis for Wyoming’s lone House seat, which was once held by her dad. After eight long years in exile, the Cheneys are back in government, and it might be a while before they go away again.

Cheney, a veteran of the Bush administration who has inherited her father’s hawkish views, is returning to a Washington, DC, far different from the one the former vice president left eight years ago. After the missing weapons of mass destruction, the Iraqi insurgency, Abu Ghraib, and the other foreign policy and national security fiascoes of the 2000s, neoconservatives lost their grip on the Republican Party. President Barack Obama’s two terms gave rise to a new kind of anti-interventionist Republican, such as Sens. Ted Cruz and Rand Paul (dubbed “wacko birds” by Sen. John McCain), who opposed intervention in Libya and Syria and criticized the growth of the surveillance state. The 2016 Republican presidential primary, with Cruz and Paul on one side and Sen. Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush on the other, was supposed to settle the question of what kind of foreign policy Republicans would push going forward.

Then Donald Trump blew up everything. With Trump, the GOP coalesced around a candidate who’d lambasted George W. Bush for invading Iraq (despite once supporting the invasion) and flirted with 9/11 truthers. He played footsie with Vladimir Putin and, according to the National Security Agency’s director, got an intentional boost from Russian hacking—all while chastising Hillary Clinton for not being tough enough. He opposed military intervention in Syria but promised to “bomb the shit” out of ISIS and, for good measure, to take its oil. He enthusiastically defended torture and said Edward Snowden should be killed. Several veterans of the Bush administration, including Colin Powell, endorsed Clinton. (The ex-president himself said he did not vote for Trump.)

Yet the Cheneys’ politics are poised to make at least a partial comeback under Trump. After the election, old hawks and Bushies such as former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, former CIA head James Woolsey, and former UN Ambassador John Bolton were floated for roles in the new administration. And Liz Cheney is not likely to sit on the sidelines. Even as her father’s dark shadow receded after 2008, she emerged as one of Obama’s most relentless national security critics. With a fervor that felt personal, she pilloried the president for changing course on torture and Iraq. But unlike many members of the Bush administration, Cheney was also an unabashed supporter of Trump, embracing some of his more heretical views on trade and immigration and warning that Clinton was little more than a “felon.” In her first week on Capitol Hill, she has emerged as one of the most vocal defenders of President Trump’s plan to bring back torture. She may just be a bridge by which the neocon establishment returns from exile.

Although her campaign ads touted her family’s deep Western roots, Cheney spent all but two years of her childhood in the suburbs of northern Virginia. As girls, she and Mary played in the White House, stealing candy from the secretary of President Gerald Ford’s chief of staff—Rumsfeld, then serving as their dad’s boss. She returned to Wyoming with her family during election season and was campaigning for Republican candidates by the time she was eight years old.

When she arrived at Colorado College in 1984, Cheney was firmly molded in her father’s image. Her views made her an outlier on a liberal campus. She helped launch a conservative students union and a right-wing publication called the Disparaging Eye. During a polarizing stint as the opinions editor at the student newspaper, Cheney irked her classmates by adding an American flag to the masthead, and she wrote earnest op-eds supporting the Contras and assailing the campus campaign to divest from apartheid South Africa.

Her senior political science thesis, “Evolution of Presidential War Powers,” argued that Congress had only limited authority to restrain the executive branch on matters of military intervention. “The president’s duty to protect national security sometimes comes before his responsibility to keep Congress informed,” she wrote. A decade and a half later, the Bush-Cheney administration would take much the same position.

After college, Cheney entered the family business, taking a job at the US Agency for International Development during the first Bush administration and working under the direction of Richard Armitage, a future architect of the invasion of Iraq. When Dick Cheney chose himself as George W. Bush’s running mate in 2000, Liz left her job in international finance to join the campaign. And in 2002, as the second Bush administration was gearing up for its dramatic attempt to remake the Middle East, Liz joined the State Department as a deputy assistant secretary focusing on the Near East. Her signature project was the $25 million Middle East Partnership Initiative, which doled out money for education and human rights. The vice president, who preferred his nation-building efforts with a few more explosions, dubbed her “my left-wing daughter.”

But if anything, she was just as much of a hardliner as he was. According to a recent biography, George H.W. Bush called Liz “tough” and speculated that she’d pushed her father to become even more hawkish.

It was her work after leaving office that may offer the best preview of why neoconservatives are so excited that Liz Cheney is back. Following the 2008 election, many of the Bush administration’s leading lights went into a sort of self-enforced hibernation. Save for a few forceful speeches trashing Obama, Dick Cheney retreated to Jackson Hole to fly-fish in peace. Into the void stepped Liz.

Her first splash came three months after the inauguration, when the Justice Department released new information on the Bush administration’s use of torture. Cheney took the move, along with Obama’s efforts to shut down the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, as a personal insult to her family’s legacy. On cable news programs and at conservative conferences, Cheney became her father’s defender in chief. “When you see the current administration making decisions that really do have the potential to make us less safe, in those circumstances, I would say the vice president doesn’t think that there’s an obligation to be silent,” she said in her fiery debut as a conservative talking head on MSNBC. “There are important reasons why we put policies in place. They clearly kept us safe for seven years.” She co-authored her dad’s memoir, a spirited defense of his tenure as one of America’s least popular vice presidents, and even half-seriously floated him as a possible presidential candidate.

But some of Dick Cheney’s biggest fans, like Rove, were speculating about Liz’s political prospects. Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol suggested that she run for president. “I was excited about Palin; I’m more excited about Liz,” the neoconservative Michael Goldfarb told New York magazine.

With Kristol, a former McCain staffer, and the sister of a man who was killed on 9/11, Cheney formed a dark-money outfit called Keep America Safe, which sought to paint Obama as weak on security. One of the group’s first ads bashed Attorney General Eric Holder for hiring attorneys who had once defended Guantanamo detainees. The spot referred to the lawyers as the “Al Qaeda 7” and asked, “Whose values do they share?” as b-roll of someone who looked like Osama bin Laden played in the background. It was like 2004 all over again.

Now, Cheney is likely to emerge as one of the most assertive insiders trying to harness the new president’s bluster and contradictory promises. “She can be an important voice for a traditional Republican foreign policy focused on standing up to tyrants and promoting democracy abroad,” says Max Boot, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a supporter of the Bush administration’s overseas adventures. “I hope that she and other mainstream Republicans can steer President Trump away from the isolationist and protectionist approach he advocated on the campaign trail.”

The chaos of the Trump campaign shattered some of the party’s long-held tenets, but neocon dead-enders who see the president as a blank slate sense an opportunity to return to influence. Cheney has already begun assembling a coalition of the willing. In the final days of the election, she started writing personal checks to Republican candidates in swing districts, future colleagues who just might remember the favor sometime in the near future. Even a Cheney can dabble in soft power now and then.