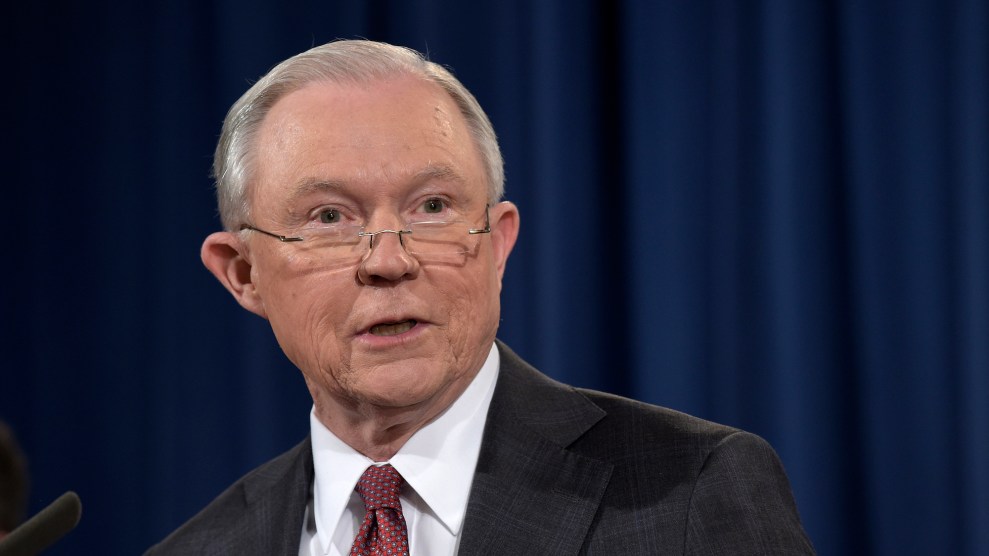

At the height of the war on drugs, a few quirks of geography conspired to place Mobile, Alabama, at the center of the action. Interstate 10, which runs through downtown, was a major drug trafficking route, carrying cocaine out west and marijuana back east. Seafaring smugglers ferrying drugs through international waters were sometimes tried in the Gulf Coast port city’s federal courthouse, where the top prosecutor was a zealous young US attorney named Jeff Sessions.

Sessions prioritized drug cases of all sizes, taking on prosecutions typically left to state authorities and often meting out long federal sentences. According to an analysis by the Mobile Register, Sessions’ policies helped southern Alabama establish a federal drug conviction rate that was almost four times the national average.

It was one such drug case that brought Miami defense lawyer Edward Shohat to the Mobile courthouse in the early 1980s. His client had helped mastermind an operation to smuggle nearly 30,000 pounds of marijuana from Colombia on a shrimping boat, but everything went wrong before the boat’s crew was discovered in Mobile Bay, floating on a bale of marijuana. Still, it wasn’t just the bizarre details of the case that Shohat remembers all these years later. What stands out in his memory is Sessions, who, according to three lawyers present, entered the courtroom during jury selection dressed in a military uniform and sat down at the prosecution’s table.

“It was so over the top,” says Alan Ross, one of the attorneys there that day. As Shohat and Ross recall, the judge ultimately sent Sessions—then a captain in the US Army Reserve—home to change. “Was he trying to prejudice the jury in some way with his military uniform?” says Shohat. “I suspect he was.”

The strange scene, shortly into Sessions’ tenure as the US attorney for southern Alabama, presaged years of less theatrical but more consequential displays of his willingness to put his thumb on the scales of justice in order to achieve his goals, sometimes through prosecutions that appeared politically motivated.

“Now Jeff Sessions owns every federal grand jury in America,” Shohat says ruefully. “Don’t get me indicted.”

Born in Selma in 1946, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III was raised in Hybart, a speck of a town in Alabama’s Black Belt, so named for its rich soil. The majority-African American area had long been a hotbed of voter suppression, where whites intimidated black sharecroppers or misreported their votes. The state’s 1901 constitution effectively disenfranchised African Americans through a combination of poll taxes, literacy tests, property requirements, and screening for past offenses such as vagrancy. As the leader of the state’s constitutional convention explained at the time, “If we would have white supremacy, we must establish it by law—not by force or fraud.” When Sessions attended the segregated Wilcox County High School, not a single African American in the county was registered to vote.

In contrast to the Black Belt, coastal Mobile entered the 20th century as one of the South’s most tolerant cities, even electing a Jewish mayor in 1911. But World War II changed Mobile, as rural whites flocked to the city’s shipyards, docks, and aircraft plant in search of jobs, bringing with them a racial and religious conservatism.

By the 1970s, when Sessions moved to Mobile not long after getting his law degree, the city had become a stronghold of George Wallace, the state’s segregationist Democratic governor. Whereas municipal governments in Alabama’s other major cities integrated, it took the US Supreme Court to bring black representation to Mobile’s city council. The last recorded lynching in the United States took place in Mobile in 1981, when the Ku Klux Klan kidnapped a 19-year-old African American named Michael Donald, slit his throat, and hung him from a camphor tree. Mobile had become a city of both old-money aristocracy and white-grievance populism—a sort of proto-Trumpism that explains why Donald Trump held one of his first mega-rallies, in August 2015, in Mobile, with Sessions at his side.

In coming to Mobile, Sessions had retraced the steps of other rural whites before him. “In North Alabama, where the knowledge economy is centered, that’s the Republican establishment,” says Alabama historian Wayne Flynt. “They never liked Jeff Sessions very much. Too many connections to race, to right-wing conservatism, to the white evangelical rabble-rousers.”

At the time, Alabama was in the middle of a political upheaval. Segregationist Democrats had long been in charge, but the national party had taken up the cause of civil rights, prompting Republicans to embrace Richard Nixon’s Southern strategy—backing the discriminatory status quo to win the votes of Southern Democrats. It was with this strategy that Sessions, who had led the pro-Nixon Alabama Young Voters for the President group while in law school, appeared to align himself.

As a US attorney, Sessions found himself at the intersection of the dual roles the federal government played in Alabama. “On civil issues and on social justice issues, people have looked to the federal courts for refuge,” explains J. Mark White, a prominent trial lawyer in Birmingham. “The contrast to that is the feeling that perhaps the federal government, on the criminal side, has been overly aggressive and maybe, some even say, politicized.” Throughout his career, Sessions has embodied that dichotomy, employing the heavy hand of government in criminal prosecutions while sometimes appearing wary of defending civil rights.

In 1965, a Baptist deacon in Marion, Alabama, named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and beaten to death by state troopers following a protest for voting rights. His killing helped spur the march from Selma to Montgomery, the “Bloody Sunday” showdown on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act. But even once they could vote, African Americans in the Black Belt struggled to get their candidates elected to local government councils and school boards.

So community organizers, led by Albert Turner, a former aide to Martin Luther King Jr., started teaching African Americans to vote absentee in order to boost turnout, particularly among elderly voters struggling to make it to the polls, which in some places were open for only four hours. In 1982, local candidates backed by Turner and his allies finally won. Two years later, Sessions began investigating absentee ballot use by African Americans in five rural counties where black voters’ influence was ascendant. He charged Turner, Turner’s wife, and another organizer—known as the Marion Three—with mail and voter fraud for allegedly tampering with ballots. During the trial, his case fell apart, and the jury found the three activists not guilty.

The case became a major issue for Sessions a year later, when President Ronald Reagan nominated him to a federal judgeship. A Senate committee blocked his nomination amid allegations of racism stemming in part from his targeting of the Marion Three. To his critics, Sessions’ handling of the case was as damning as the fact that he had prosecuted it. He could have convened a grand jury in Selma, just down the road from Marion. Instead, it was convened in Mobile, 160 miles away, where the jury would be whiter. Some of the witnesses, elderly black voters, had to board buses in the presence of armed police and FBI officers, mere feet from where state troopers had killed Jackson 20 years earlier. Once in Mobile, the witnesses were photographed and fingerprinted, Turner testified. Several were so shaken by the process that they said they would never vote again. (E.T. Rolison, who worked on the prosecution as an assistant US attorney, says grand juries had generally convened in Mobile and denies that the witnesses were photographed and fingerprinted. Sessions’ office declined to comment for this story.)

“This was not just about the prosecuting of a case,” says Alabama state Sen. Hank Sanders, who was involved in the defense of the Marion Three. “It was all kind of other symbolism involved…It was trying to get people to be scared to say anything other than what the law enforcement wanted them to say at the grand jury. And also to send a message out to the community, and to get people to be afraid to stand up and fight back, to be afraid to vote.”

Sessions presented himself as a crusader against graft, frequently prosecuting Mobile officials, often Democrats, who were still dominant in the 1980s. “He’s one of the few that is not corrupt,” says Thomas Gallion, an attorney in the state capital of Montgomery. But the flimsy evidence for some of these prosecutions drew accusations that Sessions was motivated by politics.

Shortly after Sessions was denied the federal judgeship, his office charged two African Americans who played a role in his confirmation hearings: one who had testified against him, and another whom Sessions had allegedly called a racial slur. The first was acquitted; the second spent more than five years in prison but continues to deny any wrongdoing. “I considered that, ‘How dare you? You testified against me,'” says Sanders. Sessions charged at least half a dozen Democratic politicians in Mobile, often during campaigns and with questionable evidence, according to a report in the Guardian.

In 1994, when Sessions was running for state attorney general, reporters obtained flight records showing that the Democratic governor, Jim Folsom, had flown to the Cayman Islands on the private plane of a local dog-track owner. Sessions used the revelation to attack his rival, incumbent state Attorney General Jimmy Evans, for going easy on Folsom, and the episode helped topple both Folsom and Evans.

After the election, Gallion filed a wrongful-termination lawsuit on behalf of a state employee with an explosive allegation: FBI agents working on behalf of Sessions’ campaign had helped obtain the flight records. Affidavits filed by Gallion’s client and another state employee contended that Sessions had assisted in planning the operation. A private investigator who did work for Sessions’ campaign admitted to tracking down the flight records and receiving $3,000 to cover his expenses, but he didn’t disclose who had made the payment and denied that Sessions had approved the operation. An FBI agent allegedly involved in obtaining the records had worked on several of Sessions’ investigations into Democratic officials and was later hired by Sessions to work in the attorney general’s office. Gallion tried to get the US attorney to investigate the alleged FBI misconduct, but the prosecutor, who had worked with Sessions on an anti-corruption probe, never pressed charges. Today, Gallion, who can rattle off the minutiae of every Alabama political scandal, says he doesn’t recall the details of the case. (Several lawyers once critical of Sessions seem reluctant to say a bad word about him now that he is attorney general.) Although Sessions has said he had “no involvement whatsoever” in obtaining the flight records, the episode raised questions about his willingness to tap his relationship with the FBI for political gain. It’s a troubling backdrop for the man who now oversees the bureau, given that the FBI is investigating the Trump campaign even as the bureau remains under a cloud for politically motivated leaks that helped the president win the 2016 election.

Installed in Montgomery as Alabama’s attorney general, Sessions promised to pursue corruption cases, and it wasn’t long before a big one fell into his lap. A whistleblower claimed that Tieco, a Birmingham industrial equipment company, was defrauding a client. Sessions declared the case “of the most magnitude that the Attorney General’s office has undertaken in the last twenty-five years.” The next year, Sessions’ prosecutors convinced a grand jury to hand down 222 charges against Tieco. Sessions, running for US Senate, hyped the indictments, boasting, “I have committed this office to vigorously investigate corporate white-collar crime.”

In reality, the case against Tieco was shoddily knit—once the defense began pulling at its threads, it unraveled completely.

The case originated when Sessions was approached by Victor Hayslip, an attorney representing the whistleblower. Sessions’ office obtained a sweeping warrant for Tieco’s business records and assigned former FBI agents now working for the state to investigate the case. Sessions then began a bizarre collaboration with United States Steel, Tieco’s alleged victim, by sharing Tieco’s records with the company. Armed with inside information, US Steel (which had also been represented by Hayslip) launched its own lawsuit against Tieco. (A federal judge ultimately threw out US Steel’s claims.) US Steel’s lawyers also assisted Sessions’ office on the criminal prosecution, and the company even offered to help pay for the state’s investigation. Hayslip’s firm and US Steel both contributed to Sessions’ Senate campaign, and Sessions later appointed Hayslip to a temporary deputy attorney general post.

Sensing that Sessions’ office was withholding evidence that could exonerate Tieco, the judge took a highly unusual step and ordered it to turn over all its files in the case to Tieco’s lawyers. They revealed wrongdoing by Sessions’ office throughout the investigation, including the withholding of exculpatory evidence. The state dropped dozens of the charges. Citing prosecutorial misconduct, the judge dismissed the rest and wrote a brutal opinion slamming Sessions’ office. Stephen Gillers, a professor at New York University School of Law, told the Senate Judiciary Committee in January that the opinion was “the most scathing criticism of a prosecutorial office I have read in the nearly 40 years I have been teaching legal ethics.”

“It’s all a charade,” says Bennett Gershman, an expert on prosecutorial misconduct who reviewed the case at the behest of Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee ahead of Sessions’ confirmation as attorney general. “It got him to the Senate.”

When the judge’s searing opinion came down in 1997, Sessions, by then a senator, responded indignantly. “Charges like ‘prosecutorial misconduct’ offend me,” he told the Montgomery Advertiser. He spun the case as a parable about prosecutors being “abused by defense lawyers” and attacked the judge for being “a hostile judge from Day One.”

Gershman and Gillers regard Sessions’ pursuit of Tieco with horror. “This case epitomized the worst prosecutorial misconduct that you could imagine,” Gershman says. The attorney general, Gillers adds, “sets a tone. And the concern is that Sessions, as attorney general of Alabama, did not create an atmosphere in which the lawyers who worked for him appreciated the special responsibilities that come with prosecutorial power. Now, moving to the Department of Justice, a bad tone can hurt a lot of people.”

From the moment he became US attorney general, Sessions has been embroiled in controversy. He was forced to recuse himself from any investigation of the 2016 presidential campaign following revelations that he had met with the Russian ambassador during the campaign and misled Congress about it. And his Justice Department has so far failed to successfully defend Trump’s ban on travelers from several majority-Muslim nations. Trump’s presidency will also present myriad potential conflicts of interest, testing Sessions’ commitment to rooting out malfeasance, a promise that helped him get elected as Alabama’s attorney general.

Sessions has already begun to pull the department back from civil rights enforcement. In late February, Sessions delivered remarks to a few dozen Justice Department employees to mark the end of Black History Month. Whereas Eric Holder, the first African American attorney general, had packed the Great Hall at the department’s Washington headquarters for his first such address in 2009, Sessions held his in a seventh-floor room, and his remarks lasted barely four minutes. He began by invoking his roots in rural Alabama. “Even in my lifetime, I saw discrimination firsthand,” he said, adding that “the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were pivotal points in our history.”

But the previous day, Sessions’ Justice Department had stopped the government’s push against a Texas voter ID law—signaling the administration’s reluctance to vigorously enforce the Voting Rights Act. And just hours before his Black History Month remarks, Sessions, harking back to his days as a young prosecutor, had told a gathering of state attorneys general that he planned to increase the number of federal prosecutions for drug crimes. It signaled a return to Reagan-era tough-on-crime policies that reformers, including many Republicans, now say unfairly target minority communities. “He ran it [like] what it was, a powerful machine that grinds people down,” says Domingo Soto, a liberal defense lawyer in Mobile, of the US attorney’s office under Sessions.

It seems that Sessions’ philosophy hasn’t changed much since his days in Mobile. “If I were attorney general,” he told the Mobile Register two decades ago, “the first thing I’d do is see if I couldn’t increase prosecutions by 50 percent.” Now, he has the chance to make his vision come true.