By now, you’ve probably heard that former North Charleston, South Carolina, police officer Michael Slager pleaded guilty on Tuesday afternoon to federal charges of using excessive force and violating the civil rights of Walter Scott in a police shooting that became national news. The big remaining questions are why Slager did so, and how much time he is likely to spend in prison. “It’s murder, regardless of what people think,” Ed Bryant, president of the local NAACP chapter, told reporters outside the courthouse.

Only a life sentence for Slager would be just, Bryant said: “The whole world has seen that. They know what he’s done. He killed a man by shooting the man in the back cold-bloodedly. The country isn’t going to bow down to that. No way.”

Five months ago, a Charleston jury failed to reach a unanimous verdict in Slager’s murder trial—a trial I covered for Mother Jones as part of an in-depth story on the lives of the officer and his victim, the state of police training in America, and the obstacles to convicting cops for the questionable shootings we see so often in the headlines. Here’s a scene from the Slager-Scott confrontation:

The officer returned to his cruiser intending to run Scott’s license through an FBI database, standard procedure. Scott stepped out of his vehicle and then climbed back in when Slager, sitting in his squad car, instructed him to do so. But moments later, Scott got out a second time and ran toward an open field, the site of an abandoned trailer park, and onto a painted asphalt path known locally as the Yellow Brick Road. Slager pursued on foot, warning that he was preparing to fire his stun gun: “Taser! Taser! Taser!” Scott didn’t stop, so Slager hit him with two darts.

The electricity brought Scott to his knees, but he refused to surrender. Slager then “drive-stunned” Scott—put the business end of the Taser directly on him and pulled the trigger—but could not cuff him. The men scuffled on the ground, and a winded Slager pleaded for backup. “One-five-six,” he said into his radio, calling out the badge number of the officer he knew was closest. “Step it up!”

Scott managed to break free and run away in a slow, wobbly gait. This time Slager did not give chase. He unholstered his .45-caliber Glock, took a stance, and put his left hand underneath to steady the weapon. His form was perfect, like in a training video. The only problem was that his gun was aimed at the back of a fleeing man. He squeezed off eight quick shots.

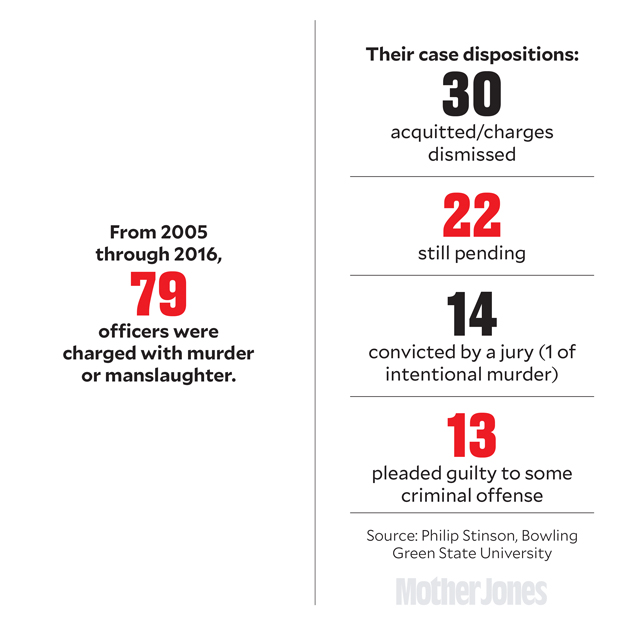

Local prosecutors in South Carolina were scheduled to retry Slager in August, but instead, as part of what is called a “global plea agreement” they agreed to drop the state charges in exchange for a guilty plea in the federal case. Slager, who will be sentenced at a later date, faces up to life in prison, but he will likely get far less. There is no mandatory minimum sentence. And, as I wrote in my prior story, the average sentence for officers convicted of murder or manslaughter over the past decade or so has been less than four years. Slager was led away after the hearing today in handcuffs. His lawyer, Andrew Savage III, said in a written statement, “We hope that Michael’s acceptance of responsibility will help the Scott family as they continue to grieve their loss.”

While reporting my story about the case, I toured the police academy where Slager was trained—for 9 weeks, as opposed to the 26 required of an NYPD officer. Inferior training was a key element of Slager’s defense. And while much of the instruction I witnessed seemed thoughtful enough, there was simply too little of it.

A report issued in March 2016 by the Police Executive Research Forum argued that misguided training—specifically, instruction that teaches officers to “draw a line in the sand” and resolve confrontations quickly—contributes directly to problematic shootings by police. Cops in training spend a median of 58 hours on firearms proficiency but just 8 hours learning de-escalation tactics to bring episodes to peaceful conclusions, according to PERF’s research. The mechanics of firing a weapon are usually taught separately from the question of when to use it.

Savage, Slager’s lawyer, had talked to prosecutors from the start about a possible deal, but they had not been able to agree on the length of a term. Although a judge will impose the sentence, Slager’s defense team and prosecutors most likely will have agreed to a sentence the government will recommend—those terms were not made clear on Tuesday. Before the deal was finalized, the government also contacted the family of Walter Scott to ascertain what penalty—if any—they would consider just. The plea deal, which you can read here, says Slager understands that the government will advocate he be sentenced under the guidelines applied to second-degree murder, the equivalent of manslaughter.

Tuesday’s plea arrangement represents a stark reversal in Slager’s account of what occurred on April 4, 2015, the day he fired eight shots at the unarmed Scott, from behind, as Scott fled. The shooting was caught on video by a bystander and viewed millions of times on the internet. Slager testified late last year that Scott was getting the better of him in a fight and he feared for his life. He told investigators initially that Scott had gained control of his Taser, though the video cast that story into grave doubt. The plea agreement states:

“The defendant used deadly force even though it was objectively unreasonable under the circumstances. The defendant acknowledges that his actions were done willfully, that he acted voluntarily and intentionally and with specific intent to do something that the law forbids.”

Philip Stinson, a criminologist at Ohio’s Bowling Green University who has done extensive research on police-involved shootings, says Slager could have decided to plead guilty for a variety of reasons. The first is that federal charges against officers who shoot and kill civilians tend to be easier to prove—though it is notoriously difficult to convict a police officer in an on-duty shooting. “His defense team may have realized the Justice Department had a good case,” Stinson says. “But it could also be that the defendant exhausted his capital in many ways, not just financial, but in terms of family considerations. He may have wanted closure.”

Slager’s lawyer took the case pro bono, and after the trial last fall said he had provided a defense that would have cost more than $1 million had he billed for it. Stinson points out that one calculation of pleading to federal rather than the state charges is the quality of the respective correctional facilities: “He may end up in a prison that is more tolerable than what would have been the case in South Carolina.”

One reason it is so difficult to convict police officers is that their jobs are, in fact, often dangerous. Police and their defense teams can effectively persuade juries that, even if they made an error in judgment, they reasonably feared for their lives. One thing that made the Slager case different—and the hung jury in the first trial so shocking to many—is that the cellphone video recorded by Feidin Santana, a 23-year-old Dominican immigrant on his way to work as a barber, seemed to show a clearly egregious act.

Slager was not under imminent threat. After the shooting, he appeared to plant evidence by retreating to where the scuffle had taken place to retrieve his Taser and then placing it beside Scott’s prone body. Slager described a different sequence of events in the hours after the shooting, but more recently he has testified that he has no memory at all of those interviews with investigators.

His memory loss could be viewed as a calculated strategy. Or, alternatively, as an indication of a defendant who was not in the best of mental states to withstand a new trial and, as he did in the state court, testify on his own behalf.