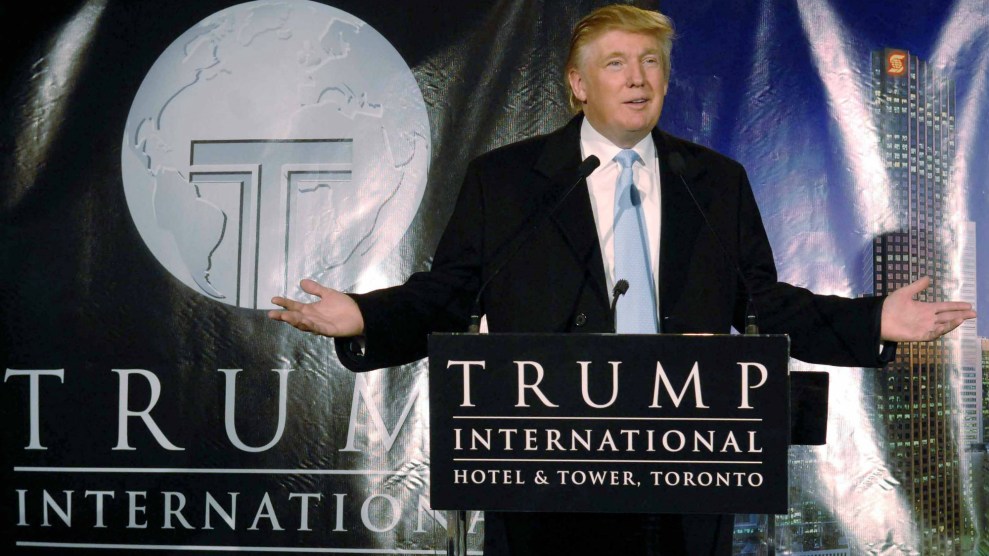

AP Photo/The Canadian Press, Toronto Star-Michael Stuparyk

Toronto has had enough of Donald Trump. After more than a decade of drama, Trump’s name is being stripped from a 65-story hotel and condo building in downtown Toronto, following years of financial failure and lawsuits. In the end, the Trump International Hotel and Tower in Toronto has become yet another symbol of the flaws of the Trump business empire: construction setbacks, strange financing, angry investors, and empty hotel rooms.

Trump first made his move into Canada at the height of his Apprentice deal-making fame, inking an agreement to attach his name—and reputation—to a shiny new Toronto tower, in which he had no ownership interest. When the building opened five years ago, Trump kicked off the project with a bit of promotion that looks a lot like the PR strategy he would employ as a candidate and as president: a tweet with a dramatic video of his plane landing and a black motorcade of SUVs rolling into the hotel’s entrance, where an adoring crowd waited.

Recently opened @TrumpToronto– it's beautiful and here is a video of the ribbon cutting ceremony.. http://t.co/VO8U2GPI

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 23, 2012

In the 2012 video—after a montage of the future commander-in-chief examining bathrooms and piles of merchandise set to jazzy trumpet music—Trump took the podium and declared, “About eight years ago I began this voyage, and it turned out to be a beautiful voyage, because the end result is this spectacular building.”

The beautiful voyage did not last. The Toronto tower he leased his name to never lived up to the hype. On Tuesday morning, the Trump Organization and the building’s current owner announced that the president’s name will be removed from the hotel.

Trump spent years promoting the property as a total success and an extension of his brand. His original partners in the project were two Russian-Canadian businessmen, neither of whom had any experience with building a skyscraper. As the building went up, construction delays and other problems—including pieces of the building falling off—set the project back.

The building was to be financed through a scheme—used in other Trump projects, such as the Trump Soho in New York City—in which investors bought individual units and signed an agreement allowing them to be rented out through the Trump-managed hotel. In return for providing money upfront for the construction, these owners would enjoy a slice of the profits when their rooms were filled by hotel customers.

Trump agreed to manage the hotel once the building was complete, but lawsuits from investors charged that Trump and his partners had misled them about his role in the building.

These investor lawsuits were not unique to Trump’s Toronto deal. He battled similar actions in relation to Trump Soho and other properties. In these cases, investors complained that they had been misled by the promotional material and sales teams that pitched the deals as successful Trump-led projects. (Trump prevailed in one such high-profile case in 2013.)

The majority of the Toronto building’s units remained unsold. (Some investors who had bought units prior to construction later backed out after the 2008 economic crisis.) Trump’s partners then turned to another source of financing. One of those partners, Alexander Shnaider, owned a stake in a Ukrainian steel mill; he sold it in 2010 and used some of the estimated $850 million in proceeds to prop up the Trump Toronto project. The buyer at the other end of the Ukrainian steel mill deal? A Russian state-owned bank known to have close ties to Vladimir Putin and now on the list of financial institutions under sanction by the US government. (In May, the Wall Street Journal reported that this deal has become a subject of interest for US investigators probing Trump’s potential connections with Russia.)

The extra financing, though, wasn’t enough, and the building remained troubled. This past November, shortly after the US election, Trump’s Canadian partners lost control of the building. It was the new owner, JCF Capital, that announced Tuesday that it was cutting ties with the Trump Organization. Given the building’s checkered history and the hotel’s struggle to succeed under Trump management, such a move made sense. Since Trump’s election, protesters in Toronto have homed in on the property as the target of their ire. Recent searches of hotel booking websites show rooms there being offered at steep discounts.

According to Bloomberg, JCF Capital may have paid as much as $6 million to ditch the Trump name. But Trump will lose a valuable revenue stream. According to the three personal financial disclosures he has filed since first announcing his candidacy, Trump has earned more than half a million dollars per year for the last three years in management fees, though he reported that his fees had fallen in the past year. (Trump’s adult sons have assumed daily control of the Trump Organization, but Trump still retains near complete ownership of the business and almost all its assets.)

The collapse of the Toronto business is the latest in a series of hits to Trump’s high-end luxury hotel empire. Questions have been raised by former employees about the source of financing of the the Trump Soho, which Trump once owned a stake in but now only manages. Recently, that hotel reportedly laid off staff and shuttered a high-end restaurant following a post-election slump in business. A new Trump-managed golf course in New York City has had its business decline in the past year, and several other Trump properties, including his beloved Mar-a-Lago, have suffered as well.

Last week, Mother Jones reported that Trump condo sales seem to be slumping, with large cuts in the listing prices for several prominent Trump-owned units in New York City. The removal of his name from the troubled hotel in Toronto is another sign that his new job—while certainly creating new business opportunities for him and his family—has posed its own set of complications.