Hans Gutknecht/Los Angeles Daily News/ZUMA

Willie Miller was born in 1948 in Noxubee County, Mississippi, an agricultural community along the state’s eastern border named after a Choctaw word that translates roughly to “stinks like fish.” As a teenager, she saw the civil rights movement transform the region, where previously no African Americans had been registered to vote. In 2000, Miller, who is black, was elected to the Noxubee County Election Commission, and she’s been reelected every four years since. Today, the county of 11,000 is more than 70 percent African American and has a poverty rate nearly three times the national average. “You got a few that’s gonna crawl out of the cotton fields and go on and do something else with their lives, and most of them are gonna leave,” Miller says. For those who stay, Miller does her best to make sure they’re able to vote.

In June 2014, Miller and her four fellow election commissioners received a letter threatening legal action if they did not purge voters from the rolls. The letter came from the American Civil Rights Union (ACRU), a Virginia-based group that has fashioned itself in recent years as a conservative counterpart to the ACLU. The ACRU requested that the commissioners reduce the number of registered voters by the midterm elections that fall because, it claimed, there were more people registered than there were voting-age citizens in the county. The commissioners wanted to fight back, but lacking the funds to hire an attorney, they decided not to respond and waited to see what would happen next.

The letter they had received was one of many that the ACRU had started sending to small, rural counties across Mississippi, Texas, Kentucky, Alabama, and Arizona the year before. These letters were part of a legal campaign spearheaded by three former Justice Department officials from the George W. Bush administration to purge voter rolls across the country. The effort began in remote areas with few resources for legal defense, but recently it’s expanded to include population centers in key swing states. Voting rights advocates worry that the campaign is targeting minorities and likely Democratic voters.

The letter to Noxubee County alleged that the county was violating a federal law that requires states to keep their rolls up to date. The commissioners maintained that they were following the law. In fall 2015, the ACRU’s attorneys began to push the commission to sign a consent decree that would commit the county to vigorous vetting of its registered voter list in order to avoid a lawsuit. Among its provisions, the draft decree would require the commission to send a non-forwardable notice to all registered voters asking them to confirm their eligibility. Every voter who did not fill it out and return it would be put on a list of inactive voters, and anyone on that list who failed to vote in two federal elections would be removed from the rolls.

The commissioners refused to sign the decree. From her years in office, Miller knew that mailings are often returned as undeliverable. A third of the county’s residents live in mobile homes, and their address are not, as she puts it, “what they should be.” Some people use PO boxes but fail to pay to keep them active. So she was adamant that she would not agree to the mailing, and negotiations broke down.

In November 2015, the ACRU filed a lawsuit against the commission in federal court, alleging that there were 9,271 names on the registered voter list in a county with just 8,245 eligible voters. The case docket was notably one-sided. The ACRU would file motions, and the commission—still lawyer-less—would fail to respond. Five months after filing the suit, the ACRU moved for a default judgement against the commission. The judge said the commission should have an attorney to go over the terms of the agreement, and the county paid a local attorney about $1,000 to help the commissioners resolve the suit, according to two of the commissioners. (An attorney for the ACRU also recalled that the county hired the lawyer, but the county’s Board of Supervisors told Mother Jones it had no record of hiring or paying an attorney in this case.) Some of the commissioners viewed him as ineffectual. “He didn’t know as much about it as my daughter do,” Miller says. His advice was to sign the decree.

“They had our backs up against the wall,” recalls John Bankhead, the commission’s chairman. Under pressure, three of the five commissioners finally signed the consent decree. Miller and one other refused. The judge declined to accept it without all five on board, and the ACRU renewed its push for a default judgement.

“We are not gonna get those [voter] cards back,” Miller told her colleagues. “I promised my voters I would look out for them, and to me, that’s not looking out for them.”

At the time Noxubee County got its letter, the ACRU’s legal work was led by J. Christian Adams, a former staff attorney in the Voting Section of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. Adams joined the department in 2005, when high-ranking official Bradley Schlozman was found by the department’s inspector general to be illegally using political ideology to fill the Civil Rights Division with conservative lawyers. Adams, a conservative attorney from South Carolina, was “exhibit A” of Schlozman’s hiring practices, a former department official who participated in Adams’ job interview later said.

Adams’ early cases at the ACRU were assisted by Christopher Coates, Adams’ former boss at the Justice Department. Previously an attorney for the ACLU, Coates appears to have undergone an ideological conversion while at the Justice Department; one colleague suggested this might have been spurred in part by the promotion of a black attorney to a job he wanted. In 2007, with Bush in office, he rose to Voting Section chief. Like Adams, Robert Popper joined the Voting Section in 2005 and later became Coates’ deputy. When he left the department in 2013, he joined the conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch, an early player in spearheading voter purge cases.

In the Voting Section, all three men were at the center of contentious debates over the direction of voting rights enforcement. In 2005, Adams and Coates made history when they brought the first Voting Rights Act case alleging black discrimination against whites—and won. The case targeted the head of the local Democratic Party in Noxubee County. Coates told the US Commission on Civil Rights that the criticism of the case within the department demonstrated internal hostility to “race-neutral enforcement of the VRA.”

In 2008, Coates and Popper assigned Adams to prosecute a case against the New Black Panther Party and two of its members who were spotted outside a polling location in Philadelphia on Election Day, one of them carrying a nightstick. When the Obama administration took over, the department’s new leadership threw out most of the charges Adams recommended. The case became a cause célèbre of the right. Adams resigned in protest of the Obama administration’s handling of the case, and Coates faced criticism from higher-ups over his work on it. According to a subsequent report by the department’s inspector general, when Eric Holder became attorney general in 2009, he was told that Coates wanted to pursue more “reverse-discrimination” cases and that Coates did not believe “in the traditional way in which things had been done in the Civil Rights Division.”

As a private citizen, Adams worked with Judicial Watch to file lawsuits aimed at trimming voter rolls, before joining the ACRU in 2013. In 2015, he became president of the Public Interest Legal Foundation, another conservative nonprofit law firm whose work has overlapped with the ACRU’s, and he sent letters similar to the Noxubee County one to 141 counties in 21 states. In 2011, he published Injustice: Exposing the Racial Agenda of the Obama Justice Department, an exposé of alleged racism against white people in the Civil Rights Division. He became a frequent commentator on Fox News and a blogger at the right-wing PJ Media, where he recently railed against the “Deep State leftists” of the “DOJ Swamp.”

To replace Adams, the ACRU hired Coates as general counsel, and the two continue to partner on voter list purges. (A spokesman for the ACRU did not respond to requests for comment from Coates.) At Judicial Watch, Popper has taken the first steps to pursue his own slate of cases. He sent letters to 11 states and 103 counties this spring warning that their voter lists exceeded their citizen voting-age populations. If those jurisdictions don’t reduce their rolls, he promises, “We will find plaintiffs and we’ll sue.”

The work, Popper says, is an extension of the enforcement that took place under the Bush administration, before voter list maintenance faded as a priority under Obama. “This is what happened at the Department of Justice,” he explains. “What we’ve imported into our institution, and Christian [Adams] into his, is the approach of the federal government.” He adds, “The federal government should be doing this work, not us. I would think the Trump administration would start it up.”

There are already indications that the administration is turning its focus to voter purges. Last week, the Voting Section sent letters to states across the country requesting information on their laws and processes for removing names from voter rolls. Vanita Gupta, who ran the Civil Rights Division during the Obama administration, warned in a statement that these requests are likely “the beginning of an effort to force unwarranted voter purges.”

Republican-backed laws requiring a photo ID to cast a ballot have attracted attention in recent years for impeding the ability of minority, poor, and elderly people to vote. But increasingly, the focus of the voting rights battle is over who gets to be on the list of registered voters. Democrats have successfully pushed for automatic voter registration in eight states and the District of Columbia, while Republicans have begun putting up roadblocks to registration. In Kansas, Secretary of State Kris Kobach, a Republican with a national reputation for crafting anti-immigrant laws and pushing the myth of widespread voter fraud, is locked in a legal battle with the ACLU over his decision to require Kansans to show a birth certificate or passport in order to register to vote. (Kobach and Adams are working together on a case to determine whether states can require people to show proof of citizenship in order to register.) Kobach was recently appointed vice chair of President Donald Trump’s election integrity commission, a perch from which he may recommend more stringent registration requirements nationwide.

The debate over voter ID “has been the most visible point of election reform,” says Barry Burden, director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “But this registration stuff is just as important but has been happening at a lower level that people aren’t necessarily aware of.”

After the civil rights movement ended poll taxes, literacy tests, and the white vigilantism that kept African Americans from the polls, states began to look for new ways to stop minorities from voting. One common and effective tactic was to create registration deadlines weeks before elections. Another, similar to the reforms the ACRU wanted Noxubee County to adopt, was to force voters to confirm their registration or be removed from the rolls. Some states purged voters who didn’t cast a ballot for a certain period of time, sometimes as little as two years. Each of these policies, which were most common in the South, adversely affected minority voters, who tend to move more frequently and vote less regularly. In 1980, the political scientists Raymond Wolfinger and Steven Rosenstone found that these tactics and a few others kept 12.2 million people from voting in the 1972 presidential election.

When the 1988 presidential election drew the lowest turnout in modern US history, civil rights groups began to agitate for national legislation to increase registration opportunities. In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), calling it “the most recent chapter in the overlapping struggles of our nation’s history to enfranchise women and minorities, the disabled and the young.” Frequently referred to as Motor Voter, the law was best known for requiring Department of Motor Vehicles offices and state public assistance agencies to allow citizens to register.

In order to win broader support from Republicans, lawmakers added a requirement that states make a “reasonable effort” to keep the rolls up to date. It is under these list maintenance provisions that Adams and Coates sue counties to purge their voter rolls, with Popper preparing to join that effort. But the cases’ allegation that the counties have too many people on the rolls is not proof of a violation of the law. The NVRA also sought to protect eligible voters from purges by placing restrictions on when and how names could be removed. Election officials can’t take people off the rolls without specific indications that they are no longer eligible, and as a result, voter rolls often lag behind population shifts, particularly in rural areas where the population is decreasing. “Right now we err on the side of letting people’s names linger on the voter rolls rather than pushing them off prematurely,” says Burden, adding, “Registration rolls do have people on them who are not eligible to vote in those places, but that’s by design.”

In 2012, Adams sued Ohio on behalf of Judicial Watch and a second conservative group, True the Vote, for inadequate list maintenance. The case resulted in a settlement in which Ohio agreed to send a notice every year to registered Ohioans who have not voted in a two-year period, asking them to confirm their eligibility. If they fail to do so and do not vote in the next two federal elections, they are removed from the rolls. In 2016, civil rights groups sued the Ohio secretary of state, charging that this policy was removing thousands of eligible voters and disproportionately targeting people of color. That case is now before the Supreme Court. If the court sides with Ohio—and Adams, Coates, and Popper, who have all filed briefs supporting the state—it could open the door to a wave of similar purges of infrequent voters in other states.

After joining the ACRU in 2013, Adams started his voter purge lawsuits by targeting rural counties in Mississippi. These were small counties with significant minority populations that were more likely to settle than shell out precious tax revenue for a court fight against former Justice Department attorneys. (Adams says that in counties with small populations, “voter roll bloat can severely skew voter participation rates” and “can serve as a catalyst for fraud.”) Some of them signed consent decrees in a matter of months. By the end of 2015, the ACRU had extracted decrees from three counties in Mississippi and two in Texas. Some decrees allowed counties to continue operating essentially as they had, but the ACRU used them to signal legitimacy to the courts and to pressure additional counties into signing decrees that were often more stringent.

Popper describes these efforts as an attempt to clean up voter rolls and restore Americans’ faith in the integrity of their elections. “Elections should be clean, just like kitchens should be clean,” he says. “You should feel like the election is clean, and that happens when there are election integrity laws and they are enforced.” Adams has warned on his blog that “aliens” are voting by the thousands and that the “Left opposes efforts to find and remove aliens on the rolls, because the aliens are voting the way they want.” The Public Interest Legal Foundation, where he is president and general counsel, recently published a two-part investigation called “Alien Invasion,” claiming that more than 5,500 noncitizens had registered to vote in Virginia and cast thousands of fraudulent ballots. The data appears flawed. “Not just incredibly inflated; designed—and specifically designed—to get inaccurate information,” says Justin Levitt, an election law expert at the Loyola Law School and a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Obama administration who reviewed the reports and underlying data. Still, Adams has taken to Fox News and other conservative outlets to publicize his reports.

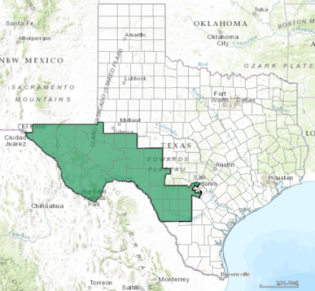

Texas’ 23rd Congressional District

Wikimedia Commons

Voting rights advocates see race and politics as motivating factors in the three lawyers’ cases, a charge the lawyers deny. In 2014, the ACRU and the Public Interest Legal Foundation targeted largely Hispanic counties in southern Texas. The first two cases were against Terrell County, a community of fewer than 1,000 people, about half of them Hispanic, and Zavala County, population 12,000 and 94 percent Hispanic. Both counties lie within Texas’ 23rd Congressional District, the only swing district in the state.

Terrell County’s sheriff signed a consent decree. But Zavala County, which sits on one of the largest oil fields in Texas history, had the money to go to court. The county hired a small team of lawyers in response to the ACRU lawsuit. Ultimately, the county and the ACRU agreed to a much weaker consent decree than other counties had. In November 2016, the ACRU, by then under Coates’ leadership, sent letters to eight more Texas counties. Four of them lie in the 23rd district, including two counties that are overwhelmingly Hispanic.

“I can’t tell you what Mr. Christian Adams thinks, but I can tell you that he is going around to places with a history of racial discrimination and seeking to have legitimate voters stricken from the list,” says Lloyd Leonard, director of advocacy at the League of Women Voters, which opposed Adams in several voting rights cases. “Draw your own conclusions.”

In Noxubee County, where all five election commissioners are black, the lawsuit was viewed as an attempt to turn back the clock on civil rights. Bankhead, the chair, got into politics as a young man in order to fight for civil rights and says the county was being picked on because it was majority-black. “They want to put us back the same place we come from,” says Miller. “But now I’m not going.”

Adams denies that his cases are motivated by race or politics. “We go where the problems are,” he says in an email. “Hardly any of the counties that received notice letters from us were minority. And of those that were sued, the facts show the alarmists are wrong. But surely we can both agree that ‘minority’ or any other cohort of voters deserve clean voter rolls, just as they would require clean water or other necessary public services.” Popper calls question of race in list maintenance a “red herring,” adding, “In order to have election integrity, you’re going to have to check things, and in order to check things, there’s always going to be a differential impact. That’s not the same as discrimination.”

Having secured consent decrees in rural counties in the South, Adams and Coates have moved on to higher-profile targets in Democratic-leaning areas in swing states, where list maintenance could take much greater numbers of voters off the rolls and have a bigger political impact. That might prove to be a mistake.

Their first target, in 2016, was Alexandria, Virginia, a strongly Democratic Washington suburb of more than 150,000 people. By this point, the liberal think tank Demos and other advocacy and voting rights groups had begun tracking these lawsuits. When the Alexandria suit was filed, a nonprofit law firm called Project Vote alerted the League of Women Voters, which tapped its Virginia chapter to intervene in the case, along with two attorneys from the heavy-hitting law firm Hogan Lovells. When the case went before a judge in June 2016, Adams was outnumbered—a situation he never faced in places like Noxubee County. He appeared alone on one side of the courtroom while the city’s lawyer was joined by five voting rights attorneys on the other. The judge, citing a lack of concrete numbers to back up Adams’ claims against the county, told Adams to do more research and dismissed the case.

A few weeks later, Adams and Coates filed a lawsuit against the supervisor of elections in Broward County, Florida, a population center of nearly 2 million north of Miami. In July, Adams filed a suit in Wake County, North Carolina, home to the state capital of Raleigh. In both cases, civil rights groups and labor unions quickly intervened. Instead of a quick consent decree, both cases began to lurch toward trials. In June, to avert a trial, Wake County and Adams’ client agreed to a settlement, in which the county agreed to pursue very basic list maintenance procedures, most of which it was already doing. (Adams claimed victory on Twitter.) The Broward County case is slated for trial in July and could prove a make-or-break moment for these list maintenance lawsuits.

Meanwhile, in Noxubee County, Miller was still fighting the ACRU last summer. With a consent decree close to being forced upon the county, she reached out to Wilbur Colom, an attorney in nearby Columbus, Mississippi, who had represented the county when the Justice Department had sued in 2005. Colom, who is African American, believed that the mass mailing the ACRU sought was designed to remove poor and minority voters from the rolls. “This is an old technique,” he says, adding, “We had to go through these processes in the ’70s and ‘80s.” He agreed to take the case pro bono.

“They had no evidence, not a single incident of any illegal vote being counted or being cast,” Colom says. (The ACRU never cited an incident of fraud in its court filings.) “There was never any intention to improve the integrity of voting. The purpose was to clean the rolls and to make sure Democrats had fewer votes.”

The lead attorney pushing for the voter purge in the Noxubee County case declined to comment for this story. Adams says some people accusing him of a racial motivation “have a history of shouting about racism when none exists. Hard to take them seriously.”

When Colom reentered negotiations with the ACRU’s lawyers, the group asked Colom to draft a decree his clients would sign. He did, and the two sides agreed to a forwardable mailing that would be sent only to 1,500 people who had not voted in five years. The decree would be in effect for just one year. On January 24, 2017, two and a half years after the commissioners received their first letter from the ACRU, Miller and her colleagues signed the consent decree.

Still, the legality of this kind of decree remains in doubt. In the Ohio case, the Supreme Court will determine whether a jurisdiction can use inactivity to trigger a voter’s eventual removal from the rolls. Coates and Popper, urging the Supreme Court to declare it legal, signed onto a “brief of former attorneys of the Civil Rights Division” arguing that Ohio’s list maintenance procedures were indistinguishable from the enforcement actions they had taken while at the Justice Department.

Popper insists that using inactivity to start the purging process is not a burden on voters. “All you’ve got to do is have some voter activity,” he says. “I mean, it’s not like getting registered to vote is like getting your law degree. It’s really easy.”

Adams is adamant that the consent decrees he has obtained have not caused eligible voters to be removed from the rolls. “You can’t find a single eligible person removed from the rolls after our settlements,” he says in an email. “I’ll send a $100 gift card to anyone you can find who was improperly removed after one of our settlements. Until then, it’s a scare tactic to push that phony concern.”

On the other side of the issue is Noxubee County’s Miller, who’s currently implementing the consent decree she signed with the ACRU in January. Already, nearly 300 of the mailings have come back to the county commission as undeliverable. Still, Miller is doing her best to keep eligible voters on the rolls. “We’re going door to door, calling, trying to find out where those people are, because we know they’re here,” she says. “The state don’t require us to go out looking for them. You don’t get paid enough to go out looking for nobody. But, you know, I’m determined.”