Courtesy: Lauren Markham

In the past five years, roughly 177,000 Central American children have arrived at the US-Mexico border on their own. Lauren Markham, a California-based reporter, set out to write a book about two of them: Ernesto and Raúl Flores, a pair of identical twins.

In The Far Away Brothers, which came out this month, Markham provides a painstakingly reported look at the gang violence and poverty that has caused countless people to flee El Salvador. She explores migrants’ often fatal journey north, and the challenges of getting legal status in the United States. But more importantly, it is a compassionate look at the lives of two young men and the family they left behind when they were seventeen years old.

In 2011, there were 4,354 murders in El Salvador, making it about a dozen times more dangerous than the United States. Two years later, Ernesto left to help support his family. Soon after, Raúl joined him. Eventually, they were detained by border patrol in the Texas desert and reunited with an older brother in California.

Markham met Ernesto and Raúl in 2014 when they were still seventeen through her work at Oakland International High School, a school for English-language learners where she coordinates programs for immigrant families and followed them through the presidential election. She did not set out to find the “perfect” immigrant and The Far Away Brothers is better because of it. Her account shows the twins struggling in school, falling in love, taking selfies, and spending money they’re supposed to be sending home to their family.

The book could not have come at a more relevant time. President Donald Trump has made MS-13, which is strongest in Central America, the focus of his anti-immigrant rhetoric. Last week, Attorney General Jeff Sessions told gang members: “We will hunt you down.”

But the political rhetoric often ignores the questions Markham poses: “Why is Central America hemorrhaging people? And what can be done to stop it at the source?”

I spoke with Markham about how the twins experience compares to those of her other students and the history of US involvement in El Salvador.

Mother Jones: What led you to write about Ernesto and Raúl in particular?

Lauren Markham: What was so compelling to me is that they were twins. They had this identical upbringing and were totally attached at the hip, but they were really different people. And even though they were separated for part of it, they had a similar migration story. But they had really different reactions to what that experience was. And I also wasn’t just going to pick the craziest, hardest story. I think that the nuances of these young men’s story is actually what’s more interesting. They weren’t gang members. They weren’t threatened in the same way as a lot of my other students.

MJ: Can you give a brief history of migration between El Salvador and the United States?

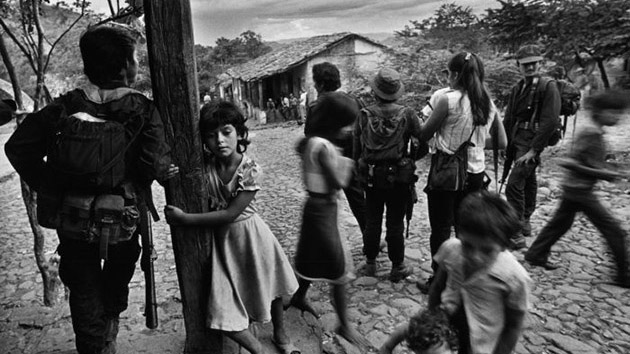

LM: Definitely immigration from El Salvador is not new. The original mass exodus was in the 80s during the civil war. Hundreds of thousands of people left El Salvador and went to the US. The current violence looks really different than it did during the civil war because it’s not two armies fighting. But a lot of people have [asked] what is the difference between this and war? It’s a war zone. There are rivaling sides. And they’re fighting for power.

The victims are everybody. But the victims are particularly young people who make up the vast majority of the gang’s foot soldiers. There’s really not much of a difference between young gang members and child soldiers in terms of the dynamics. Young people are forced into gangs either by actual force or by force of circumstances. Because of that, as the gang violence has spiked, so has the exodus of young people leaving the country. I think many of us would make the same decision.

MJ: Has the United States contributed to that violence?

LM: We have a strong responsibility for what’s happening in Central America because of the historical legacy of our intervention there. We funded the government’s forces in El Salvador. Both sides played dirty in that war, but we definitely supported the bad guys. They were going into towns and putting everyone in a church and lighting them on fire, hacking babies to death in front of their mothers to terrify people into not joining the [left-wing] guerillas.

We supported the wars to avoid the spread of communism. And that meant we traumatized generations of people but also meant that a ton of people left. And when those people left, they came to the United States. They had limited opportunities in the United States. They were traumatized by the war and that is where MS-13 got its start, mostly in LA. And then many of those people who started MS-13 went to jail and were deported back to El Salvador. The fact is we were a cause of the original seed of MS-13.

MJ: Getting to the United States is often incredibly expensive. You write about the problems of debt for these families. Could you describe what happens?

LM: I think one of the least talked about and least understood things is the extent to which this debt totally cripples people when they get here, especially young people. An $8,000—or in the case of the twins almost double that—debt to get to the United States, that is so much money to pay off at that compounding, predatory interest rate. There’s this idea that all this money is going back to El Salvador in remittances, but that money is going back to pay debts.

MJ: What does all this debt mean for unaccompanied minors and their families?

LM: We have this idea of immigrants who come to the United States and pull themselves up by their bootstraps. If you arrive saddled with debt, that’s a much more difficult thing to do. You’re just so distracted by this debt that going to school is complicated because you have to have a job. The impact of the debt and then the impact of being in charge of these high-stakes finances as a young person is not to be underestimated. We have a handful of students who drop out every semester because [they say] “I just have so much debt. I have to work.”

And then for the families, people all throughout Central America are losing their homes or losing their land. What will happen is: “OK, we’re really deep into debt. Let’s go into more debt and send another person north because maybe if we do that then that person can help make enough money to send money back.” So it’s just a constant debt cycle.

MJ: What is something that surprised you while reporting your book?

LM: It was interesting for me to see first-hand how gang members are similar to the students I have here. It’s really easy to just think of people who do bad things as bad guys, especially when they’re far away and they’re sort of exoticized by the media. I just had this moment when I was at the morgue and they were carting this kid in—and similarly when I was at a police station and I saw all these young men on their knees with their hands behind their heads as an armed guard marched back and forth—it was just, “Wow, these young people look so much like my students.” Shift their lives, or their trajectories, two degrees this way and they would be my students. I knew that statistically, but it was really visceral to see it in action. And to realize that this is like a child soldier situation. This is a really entrenched dynamic in which young people are entering into this world at such young ages they’re almost incapable of understanding the impacts of those choices.