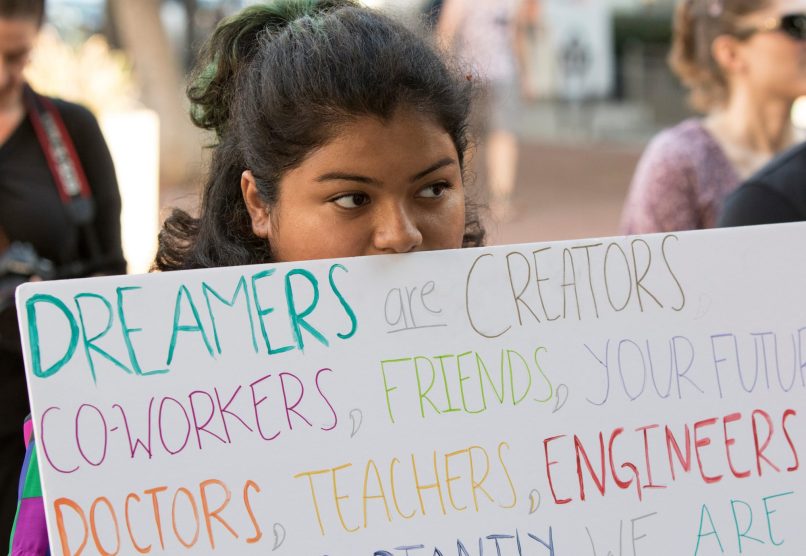

Hundreds took to the streets of downtown Santa Ana, California to protest the removal of DACA on September 05, 2017.Kevin Warn/Zuma

Her classmates were queasy when a science teacher assigned them to dissect a cow’s eye sophomore year in high school, but Amzi couldn’t have been more excited. “I was like, ‘yeah, give me the scalpel!'” she says. Now, the 21-year-old, who prefers we don’t use her last name to protect her identity, is preparing to graduate college in California with a nursing degree in June. She’s been looking forward to launching her dream career in medicine—but her plan hinges on whether she will still have legal status to work in the US come spring.

On September 5, the Trump administration announced it would start winding down the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides protections for 800,000 young adults, known as Dreamers. Amzi, who grew up in Mexico City and was brought here by her parents before the age of 16, is one of an estimated 154,000 immigrants eligible to apply for the program’s final round of two-year work and study permits. Those whose permits expire before March 5, 2018 can submit their application for a final renewal by October 5, this coming Thursday. (The Obama-enacted program originally allowed an unlimited amount of renewals.) Congress has six months to create some sort of replacement legislation before hundreds of thousands of students and young adults lose their legal status.

Trump’s announcement gave eligible Dreamers only a month’s notice to scrounge up the $495 renewal application cost. Nonprofits and government organizations have stepped in to help: Mission Asset Fund, a nonprofit in the San Francisco Bay Area, is covering Amzi’s application, along with that of 6,000 other Dreamers; Rhode Island and San Francisco are sponsoring applications as well.

Amzi’s parents moved to the US on work visas when she was six years old, leaving Amzi behind in the care of her grandmother in Mexico City. Two years later, she packed her bags to reunite with them. “It was all very abrupt and sudden,” she remembers. “There was a really long time where I was here on an illegal basis and as I got older, I became more and more aware of that,” she says.

When applying to colleges, Amzi knew it would be impossible for her family to afford the out-of-state tuition she’d be forced to shoulder as an international student; she ended up enrolling in a local community college because it was the most affordable. In 2013, her DACA application was accepted and she qualified for in-state tuition and eventually transferred to a local university.

Her degree has given her the technical skills she’ll need to work as a nurse, at a time when the country is sorely in need of more of them: According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there will be more than one million open nursing positions between 2012 and 2022. But since Trump’s inauguration, Amzi’s felt a “shift” in the way people view her and, she thinks it’s impacting her job applications. “The President has opened a window for people to voice their opinions in a negative way,” she says. “It limits the way [Dreamers] think about where we can work and what schools we can go to.” For instance, she was invited to apply for an administrative position at a private clinic. But after she submitted her paperwork, the hiring manager stopped returning her calls.

Amzi’s been told that it takes about three months for DACA renewals to be processed. Since filing her application on September 28, all she’s been able to do is wait. “The big possibility of me having to go back to Mexico City is not what I wanted or planned for my future,” she says. “I grew up here, I’m earning a degree here—and I’m hoping to use it here.”