iStock/Getty

This story originally appeared on ProPublica and was co-published with WBEZ Chicago’s “Every Other Hour” series and the Chicago Sun-Times.

John Thomas set up the deal the way he had arranged nearly two dozen others. A friend said he wanted to buy as many guns as he could, so Thomas got in touch with someone he knew who had guns to sell.

The three of them met in the parking lot of an LA Fitness in south suburban Lansing at noon on Aug. 6, 2014. Larry McIntosh, whom Thomas had met in his South Shore neighborhood, took two semi-automatic rifles and a shotgun from his car and put them in the buyer’s car. He handed over a plastic shopping bag with four handguns.

None of the weapons had been acquired legally—two, in fact, had been reported stolen—and none of the men was a licensed firearms dealer.

Thomas’ friend, Yousef, paid McIntosh $7,200 for the seven guns. He always paid well.

Thomas did little but watch the exchange, but he got his usual broker’s fee of $100 per gun, $700 total. It was “the most money I’ve seen or made,” he recalled—his biggest deal yet.

It was also his last.

Amid Chicago’s ongoing epidemic of gun violence—with nearly 500 people killed in shootings and more than 2,800 wounded this year through September—the availability of guns has been blamed as a root cause and become a defining political and public safety issue.

City police have seized nearly 7,000 illegal firearms so far in 2017 and federal authorities have stepped up efforts to take down dealers.

Still, it’s by no means clear that targeting those like John Thomas makes a real difference.

Most of the guns police seize come from Indiana and other states where firearms laws are more lax, police and researchers have found. After they were purchased legally, most were sold or loaned or stolen. Typically, individuals or small groups are involved in the dealing, not organized trafficking rings, experts say.

Unlike the drug trade—often dominated by powerful cartels or gangs—illegal gun markets operate more like the way teenagers get beer, “where every adult is potentially a source,” said Philip Cook, a researcher at the University of Chicago Crime Lab who’s also a Duke University professor.

Under pressure to respond to the violence, law enforcement has focused on making examples of people caught selling, buying or possessing guns. But authorities acknowledge that these cases do little to stem the flow of guns into the city.

“You are a single salmon swimming upstream at Niagara Falls,” said Anthony Guglielmi, a spokesman for the Chicago Police Department. “If your policing strategy is to decrease the number of guns in your city, good luck, because there are too many guns out there. It’s better to go after the person with the gun.”

An in-depth examination of Thomas’ case—based on police reports, court records and interviews, including a series of conversations with Thomas—shows how authorities target mostly street-level offenders, sometimes enticing them with outsized payoffs. In this and other cases, critics say their techniques raise questions of whether they are dismantling gun networks or effectively helping to set them up.

“You have this specter of whether it’s creating crime, which is troubling to a lot of people,” said Katharine Tinto, a professor at the University of California Irvine School of Law who has studied the investigative tactics of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “It’s not as if you’re trying to get someone you know is a violent gun offender. You’re going after someone and purposely trying to entice them into doing a felony.”

A Natural Salesman

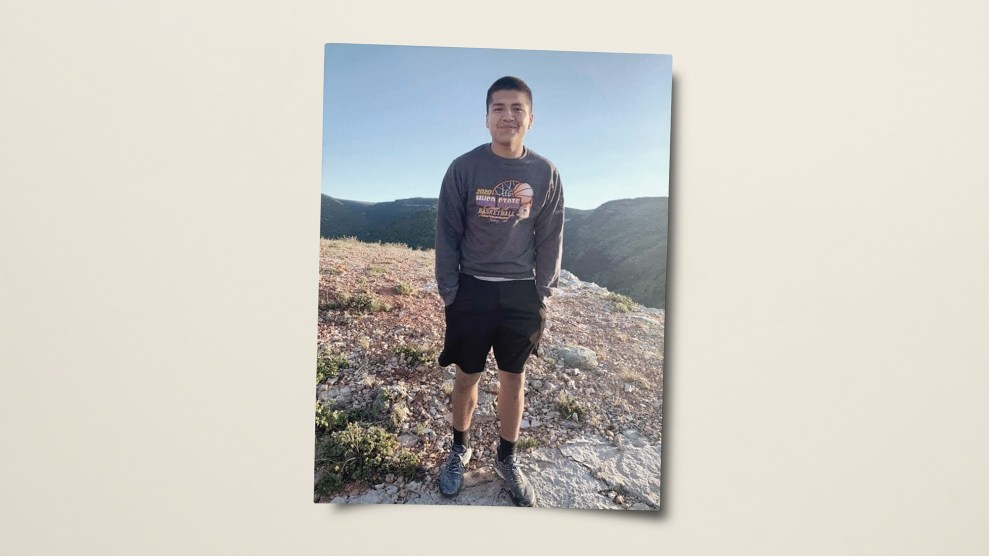

At 33, John Thomas has a charming smile that sometimes displays his chipped front tooth. His mother’s name, Val, is tattooed on his left forearm—a tribute to her for bringing him into the world, though he said he could never count on her. His daughter’s name, Jataviyona, is tattooed on his right shoulder.

Even as a kid, Thomas was a natural salesman, quick with a hustle.

“That’s my gift, I guess—to sell,” he said.

He grew up in the part of South Shore known as “Terror Town.” A short walk from a popular Lake Michigan beach, it’s long been a mix of middle-class homeowners and lower-income renters, with bungalows, condominiums and multi-unit apartment buildings on tree-lined streets.

By the time Thomas was growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, the neighborhood was struggling. Many white homeowners and merchants had fled after African-Americans moved in. Thousands of people in South Shore and surrounding communities lost their jobs when the nearby steel mills closed. When the crack epidemic hit in the early 1990s, gang violence soared.

Thomas’ father wasn’t around, and his mother struggled with addiction, according to Thomas and a younger sister, Sade Thomas-Adams. With five other siblings, Thomas was raised by an aunt and uncle he considered his parents.

Thomas’ uncle was a pastor, and the family spent a lot of time at church, giving him a lifelong faith. During the week, the kids were told to focus on their studies and come home right after school to avoid the dangers of gangs and drugs. Thomas and some of his siblings chafed at those rules, though, escaping from the house to hang out with friends, drink and smoke marijuana.

“They had their foot in both worlds—the church and the street,” said Thomas-Adams.

Thomas developed his first hustle while in grammar school, he said. He and his friends would offer to help shoppers with their bags and carts outside an Aldi supermarket. He learned he could talk to people and earn tips.

Thomas graduated to other ways of making money. First, he said, he sold baggies of fake marijuana. Eventually, neighborhood dealers set him up with real drugs.

In November 2001, when he was 17, Thomas was arrested for selling $20 worth of crack cocaine to an undercover police officer, and was convicted and given probation. The incident was one in a long string of cases, including a 2005 gun possession conviction.

After that, Thomas began to sell marijuana and developed a successful promotional strategy. When customers bought a nickel bag—a small quantity for $5—he gave them another for free. “Two for five,” was how he marketed it. His profits, he said, came from volume.

“Everybody wanted it,” he said.

When he was 20, Thomas began to hang around a new neighborhood store so much the family who ran it offered him a job. Once again, he put his people skills to work. The store sold knockoff gym shoes, but some people didn’t want to come there because it would mean crossing gang lines.

“So I’m taking the shoes to them,” Thomas said. “I’m selling them shoes left and right.”

Gang violence was a stubborn problem in the neighborhood, and moved ever closer to Thomas. At 16, he said he witnessed a fatal shooting. At 18, an acquaintance killed one of Thomas’ friends. Then, at 22, his best friend from childhood was gunned down.

Thomas said he tried to steer clear of guns.

“I know what they have done to people,” he said.

A New Friend, and an Opportunity

In late 2013, Thomas was desperate. Then 29, he was a new father and the primary caretaker of his daughter, and trying to leave criminal life behind. For several years, he’d worked low-paying jobs at restaurants, grocery stores and an uncle’s construction business, but he struggled to pay his rent. As a convicted felon, options were limited.

Then, he met Yousef.

Thomas had taken a job at a tobacco shop in the Beverly neighborhood, making $25 a day, he said. There, he hit it off with one of the guys who hung around the store. Yousef was in his 20s and, like Thomas, joked a lot. They started smoking marijuana together. Thomas said Yousef—who, through his lawyer, declined to comment—knew he was broke. Yousef told Thomas he could help—if Thomas helped him.

“He comes in and asks me about guns,” Thomas said. “I said that where I’m from, we don’t sell guns.”

But Thomas said Yousef kept bringing it up. At some point, he said, Yousef told him he knew a businessman named Pops who could give Thomas a real job if he helped them.

What finally persuaded Thomas, he said, was the dollar-store diapers he’d been buying for his daughter: They sometimes gave his daughter hives. He saw the diapers as a sign he was stuck, and his daughter was paying for it.

“It was just hard,” he said. “Too hard.”

Thomas made his first call—to one of his cousins—in January 2014. Steven Thomas, 38, had served time for attempted murder in his early 20s, court records show. Now, he was trying to rebuild his life. After earning an associate’s degree in prison, he was working to support his family and taking classes to become a massage therapist.

Thomas asked if his cousin knew anyone with guns to sell.

“The first thing he asked me was, ‘Is everything OK?'” John Thomas recalled.

He said his cousin wasn’t sure at first but called back the next day: He’d come up with a couple of guns. John Thomas got in touch with Yousef and introduced him to his cousin at the tobacco shop. He said they went to the back of the store, and when his cousin left a few minutes later, Yousef paid John Thomas $200 for arranging the deal.

“Just for a call,” Thomas said. “I didn’t even have to do nothing.”

Thomas, giddy, said he used the money to buy food, baby formula and better diapers.

What Thomas didn’t know was that Yousef had paid Steven Thomas $400 for a Glock 9mm pistol—then immediately resold the gun for $800, court records show. Even after he paid Thomas, Yousef made a quick $200.

Everyone seemed to come out ahead. So the next day, the three men did it all again. Thomas talked with his cousin, who then sold two guns to Yousef, and Thomas made $100. Yousef then sold the guns to Pops for $1,600, twice what he’d just paid for them.

To Thomas, it was easy money—money he needed.

Warning Signs

Thomas didn’t know, however, that Yousef was being watched by federal agents.

In January 2014, shortly before Yousef approached Thomas, the ATF had launched an initiative in Chicago to “attack violent crime associated with illegal firearms and narcotics.” As part of that effort, the ATF called on a longtime informant.

“Confidential Informant 1,” as he was identified by federal prosecutors, is not named in court records. He had worked for the government for nearly a decade, since being indicted for fraud and agreeing to cooperate. Gray-haired and squat, the informant posed as a businessman who wanted to buy weapons he could sell overseas, according to undercover ATF recordings and court records”

One of the people he approached about getting guns was Yousef. Authorities have not said why they targeted Yousef and why the informant’s cover story involved selling guns overseas.

Through a spokeswoman, the ATF declined comment.

In January and February 2014, Yousef met with the informant, whom he knew as Pops, eight times for deals that involved 13 guns, according to court records. Some of those deals involved guns Thomas helped Yousef buy from Thomas’ cousin, the records show.

That March, ATF agents confronted Yousef: With Pops’ help, they had been monitoring his gun deals. Yousef faced the possibility of going to prison for unlicensed gun dealing. Or he could work for the government.

Yousef agreed to cooperate. In court records, he became “CI-3,” and has not been identified by last name in Thomas’ case. From March to July 2014, the government paid Yousef a total of $6,380 for “living and operational expenses” in addition to the money he used to buy the guns, court records show.

Yousef got to work lining up more gun deals, continuing to use Thomas as his primary, but not only, middleman. After his cousin, Thomas brought in an old friend: Anthony Logan, whom everyone called Snake. Thomas told Logan he knew someone who often overpaid for guns.

In the spring and summer of 2014, Thomas, Yousef and Pops did several deals with Logan, who introduced them to other friends. When those sources dried up, Thomas arranged quick exchanges in an alley with people he didn’t know himself. There were handoffs in parking lots and a trip to Gary, Indiana, where the deal nearly unraveled and Thomas, hoping to salvage it, wandered the streets until he found the seller.

After each sale, Yousef met with ATF agents and turned over the guns and recording equipment he had secretly been wearing, according to court records.

As the money kept coming in, Thomas overlooked warning signs. One seller even tried to tell him he might be dealing with informants.

“My people are leery about you all,” Thomas told Yousef after talking with a gun source in the south suburbs, according to an ATF report. “They say you all the feds.”

Yousef vowed that he wouldn’t do any more business with that supplier.

Still, Yousef seemed willing to buy anything. While some of the deals produced semi-automatic rifles and high-powered handguns, he also bought guns that were rusty or missing parts. On one occasion, Thomas even got Yousef to pay $700 for what turned out to be a BB gun—another warning sign Thomas ignored.

‘I Ain’t Been Doing Nothing.’

That summer, as politicians struggled to deal with violence in the city, Mayor Rahm Emanuel appealed to the Obama administration for help getting guns off the street. The ATF responded by announcing it was sending seven additional agents to Chicago.

At the same time, the number of sales Thomas had brokered passed 20, and he had to expand his sources to continue producing guns. He reached out to Larry McIntosh, the friend of a friend from the neighborhood.

McIntosh proved to be a consistent source. He sold Yousef more than two dozen guns in the summer of 2014 and promised even bigger deals through a connection in Indiana.

That August, he offered a package of at least 14 guns. Yousef and Thomas were set to make the buy on Aug. 26, according to ATF records. But Thomas said Yousef called him at home that morning and asked if they could meet for breakfast to talk about a job offer from Pops. Wearing a favorite Blackhawks shirt and nice jeans, Thomas stepped outside.

“It was, like, 5 in the morning,” Thomas recalled. “I see a gray PT Cruiser [with] a white lady, she’s got a computer, and I’m thinking, what is she doing in this neighborhood at this time of the morning? I look on my left, and I see a gray van, and there’s some white guys in it, and I say, ‘Whoa, whoa, this is not right.'”

Moments later, one of his uncles arrived to give Thomas a ride, and they left. They had gone only a few blocks when police lights flashed behind them. Thomas was whisked to an ATF facility, where he was read his rights and questioned by two agents, according to the ATF’s video of the interrogation.

The agents told him he would be charged with being a felon in possession of a firearm.

“Me personally, I ain’t been doing nothing,” Thomas protested.

The agent leading the questioning showed Thomas a picture. “There’s you, holding a gun.”

After a long pause, Thomas said, “I didn’t buy nothing.”

“You didn’t have to buy anything,” the agent said. “We have you on video, holding guns. You set up all the deals.”

Thomas wanted to know if Yousef had been working with agents from the beginning.

One of the agents said no but encouraged Thomas to become an informant. Thomas refused.

‘Like Buying a Pack of Cigarettes’

The next day, the U.S. attorney’s office in Chicago announced 14 arrests on federal charges of illegally possessing or selling guns. Thomas was listed as the top defendant, followed by 13 other men involved in the deals with Yousef, including Logan, McIntosh and Steven Thomas.

If officials knew the original sources for the guns, they were not named in the court records.

In 2015, one at a time, the men entered guilty pleas. McIntosh—who two decades earlier was convicted of involuntary manslaughter after he accidentally shot a woman in the head—was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Logan got eight years and four months. The others received between 18 months and eight years.

In every case, prosecutors noted the gun violence battering Chicago and called for sentences long enough to send a message.

Many of the defendants, through their lawyers, insisted they had never sold guns until Yousef started offering to buy them.

“The government is not seeking to arrest those who are unlawfully selling weapons but effectively making gun dealers out of street level hustlers by paying three and four times the street value of guns,” Ralph Schindler Jr., who represented Logan, said in a court filing.

The ATF’s tactics are, in some ways, similar to how federal authorities battle other issues. With political corruption, they have used cooperating witnesses to offer bribes to elected officials. Fighting terrorism, they have contacted and enticed disaffected young men to discuss possible plots. Whether any of those targets would have acted without prodding is hotly debated following an arrest.

The ATF spokeswoman would not discuss the agency’s broader strategies.

“We try to hit the top people as much as we can,” said a federal law enforcement official who spoke on condition of anonymity. “They’re tough cases to prove. If we can get them on one gun, we can get them off the street.”

Wesley Pickett, who is serving eight years for helping Yousef buy guns, admits he was wrong to get involved. But he argues that putting people like him in prison will not stem the flow of weapons.

“Getting a gun in the city,” he said in a letter from a federal prison in Pennsylvania, “is like buying a pack of cigarettes at a gas station.”

Facing Prison

Yousef, too, pleaded guilty to unlicensed firearms dealing. He has not yet been sentenced.

After three months in jail following his arrest, Thomas made bail and, in spite of his pending case, got a job as a stocker at a Family Dollar store in Englewood. Within the year, he was promoted to manager.

Thomas blames himself for going after the money in the gun deals. But he doesn’t believe he played a role in Chicago’s gun violence. Though he is streetwise from years running his hustles, he said he believed Yousef’s claims that the guns weren’t headed for the streets. In time, Thomas said he stopped thinking about what was happening to the guns.

“Honestly, after a while, once [Yousef] told me that, I didn’t really care no more,” he said. “I just knew that my daughter was straight.”

As it turned out, the guns never got back to the street. The ATF bought or collected all of the guns Yousef purchased through Thomas.

In March, Thomas pleaded guilty to two counts of being a felon in possession of a firearm and one count of unlicensed firearm dealing. Prosecutors said that, over the course of seven months, he brokered 23 transactions involving 77 guns.

He faced 25 years in prison.

In August, Thomas went before U.S. District Court Judge Andrea Wood to be sentenced. Wearing a tan suit, tan shirt and blue tie, Thomas was accompanied by his daughter, the aunt who raised him, other family members and his pastor. At one point in the sentencing, he wept.

Nicole Kim, the federal prosecutor, gave him credit for working and caring for his daughter, then 4, but argued that a message should be sent that “if you need extra money, if you need a job, this is not OK.”

“He’s not proud of what he did,” said Heather Winslow, Thomas’ attorney. “But absent the influence of the government’s buy money, this crime would not have happened.”

Given the chance to speak, Thomas became emotional.

“People make mistakes, and I did,” he said. “I’m not a gun salesman.”

The judge noted that the government played a role in every deal for which Thomas was being sentenced. But, in spite of the government’s involvement, she told him he should have said no.

“It is difficult in some ways to reconcile the responsible worker and father I’ve seen in my courtroom with the person who would be willing to move 77 firearms,” Wood said.

The sentence: seven years in prison. She allowed Thomas to spend several weeks with his daughter before beginning his sentence.

On Oct. 9, he reported to a medium-security federal prison in central Illinois.

WBEZ Chicago’s Joe DeCeault contributed to this story.