Mother Jones illustration

For almost a decade, Dr. Graham Chelius has worked as a family physician and an obstetrician in western Hawaii, one of the most progressive but far-flung and isolated regions in the country. He has delivered 800 babies on Kauai, where he works as the chief medical officer for the Kauai region of the state’s largest hospital network. But though he would like to provide abortions, Chelius has never terminated a pregnancy on the island, and the hospital where he works doesn’t offer the procedure. And despite the state’s strong legal protections for the procedure, there are no abortion providers at all on Kauai, an island of almost 67,000 people. But that’s not for lack of demand.

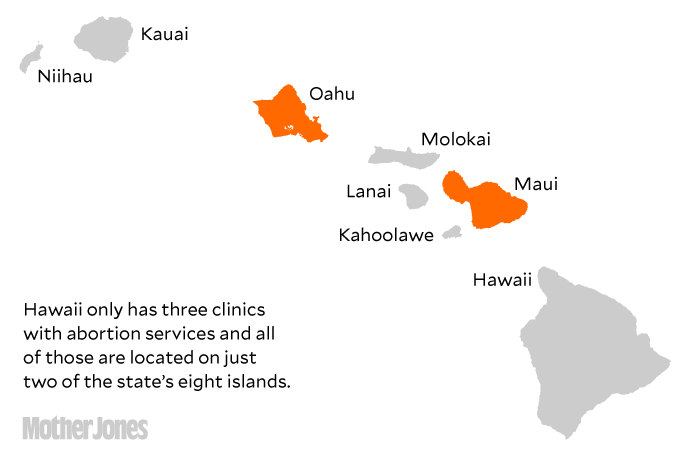

In fact, only two of Hawaii’s eight major islands have at least one publicly advertised abortion provider, forcing thousands of women in one of the country’s most reliably blue states to either buy plane tickets or carry their pregnancies to term.

“Hawaii is in the small group of states that have legally protected abortion rights. You do not see the kinds of restrictions you see in other states,” says Elizabeth Nash, a senior state issue manager at the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive policy research organization. “But that’s different than access. Because of the state’s geography and other factors, the right to choose is a right in name only.”

Access to Abortion in Hawaii

Hawaii has long been at the forefront of efforts to protect and expand access to reproductive health care. In March 1970, it became the first state in the country to pass an expansive law protecting a woman’s right to end her pregnancy—three years before the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion nationwide. Since then, Hawaii’s consistently Democratic Legislature has enacted some of the country’s most progressive reproductive rights policies: It’s one of only a handful of states that voluntarily use public money to pay for abortions; it requires even pro-life pregnancy centers to give abortion information to clients; and in 2006, it codified into law a woman’s “right to choose” abortion, should Roe ever be overturned. The state has only a few legal restrictions on access: a requirement that abortions be performed only by physicians in licensed clinics, and a caveat that no physician or hospital can become liable for declining to provide the procedure.

As a result, on paper, Hawaii is one of the best states in the country for abortion rights. The reproductive rights advocacy group NARAL consistently ranks the Hawaii Legislature among the most pro-choice in the country, along with that of California, Oregon, Washington, and Connecticut. “Our state Legislature is very supportive of family planning,” says Laurie Field,* the legislative director of Planned Parenthood’s lobbying arm in the state, “and so we’ve been fortunate to have them be our champions and help us push through legislation that expands reproductive access.”

But on the ground, many Hawaii residents still struggle to find abortions providers. Their obstacles mirror those of women in other states—abortion clinics, mostly concentrated in urban areas, are largely absent in rural communities—but the state’s geography makes traveling far more difficult. Hawaii’s three clinics are located on just two islands, Oahu and Maui, meaning at least a fifth of the state’s residents live on islands without one.

It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly why there aren’t any abortion providers on the state’s other islands, say experts like Patricia Steinhoff and Meda Chesney-Lind, both professors at the University of Hawaii-Manoa. Steinhoff, who helped conduct the country’s first-ever study of legalized abortion in 1971, emphasizes that there is a shortage of doctors across medical fields in the state. Adding to that, says Steinhoff, in the small, rural communities on the islands where conservatism and moral objection to abortion are more pronounced than in dense cities, being an abortion provider is highly stigmatized. As a result, physicians who are qualified to provide abortions might choose not to.

Take Chelius’s practice. The Kauai Veterans Memorial Hospital where Chelius works does not offer any kind of abortion service because some of his colleagues, he says, have moral objections to the procedure. Under state law, any physician or hospital can refuse to offer abortion services without fear of legal retribution. (In contrast, a physician who refuses to prescribe birth control to a patient, for example, could be sued.) Though Chelius says that he would like to provide medication abortions—the cheapest and least invasive method of terminating a pregnancy—and that he’s qualified to do so, he has decided not to press the issue to avoid enraging his colleagues. And because of an obscure Food and Drug Administration rule, Chelius also can’t provide medication abortions at the hospital without involving his colleagues.

The rule, which is the subject of a lawsuit Chelius brought against the FDA in October, requires that physicians dispense the abortion pill Mifeprex in person. Under the rule, providers must first register with the drug’s manufacturer to stock the drug. As result, Chelius’s hospital doesn’t stock Mifeprex, and his patients, most of whom live in the most remote parts of an already remote island, are forced to travel more than 100 miles east to the nearest provider on Oahu.

The stigma that comes with being an abortion provider is also present on the islands where abortion is available. At the Queen’s Medical Center, the largest private hospital in the state, located on Oahu, only two OB-GYNs out of nearly 100 provide abortion services. But, according to one employee, they don’t advertise their services publicly so that their communities don’t know what they do. Reni Soon, an assistant professor at the University of Hawaii’s medical school and an abortion provider on Oahu, says that being known as an abortion provider can lead to harassment, especially in communities where “everyone knows everyone,” as is the case in many rural areas of the state. “Being the target of that kind of opposition and sometimes hostility can be very isolating.”

The costs quickly add up for patients forced to travel to another island for health care services. In addition to the abortion itself, which can reach up to $1,000, and the cost of travel—at times more than $300—women on Hawaii’s most remote islands have to arrange at least a day’s worth of travel and accommodation in order to access abortion services. And when a follow-up appointment is needed, so is a night at the hotel. That’s in addition to the other obstacles—like arranging childcare and finding time to take off work—that all women face before an abortion. Overall, at least 260,000 Hawaii residents, or almost 20 percent of people in the state, live in areas so rural they would have to book a flight to even access abortion services.

The women most affected by the lack of abortion providers tend to be young, low-income women of color. And though Kauai has a relatively low poverty rate compared with other islands lacking abortion providers, Chelius points out that “even for a woman who has means, it’s still difficult.” Chelius told me about one of his middle-class patients at the Kauai Veterans Memorial Hospital in Waimea, Kauai, a town with a population of just fewer than 2,000 people. The woman, who already had several children when she recently became pregnant, was unable to fly to Oahu. She couldn’t take time off work or find childcare for the day-long trip, and as a result she was forced to carry her pregnancy to term.

Reni Soon provides nearly 30 abortions a week at the Oahu-based Women’s Option Center and the island’s Planned Parenthood. Around a third of her patients fly in from other islands specifically for abortion services,but she believes there would be more if they could afford the plane trip. “I’m sure there are patients I’m not seeing because they can’t get over,” says Soon. “That’s absolutely a problem.”

Making matters worse, abortion clinics in the state have been closing in recent years. Since 2011, the number of clinics throughout Hawaii decreased from six to three. That drop is rivaled only in a handful of red states, including Missouri, Texas, Utah, and Arizona, where conservative legislatures have passed one abortion restriction after another for decades. The disparity in abortion access is also caused by a broader doctor shortage in rural parts of Hawaii, according to Steinhoff and Chesney-Lind. Large swaths of the state are designated “medically underserved areas” by the US Department of Health, as determined by the number of primary care providers and the poverty rate, among other factors, and abortion care is no exception.

Chelius says many of his patients who can’t afford the time and money it takes to travel for abortion services are forced to carry their pregnancies to term. The situation is even more dire on some of the state’s smaller islands, like Molokai and Lanai—population 7,345 and 3,135, respectively—which also don’t have childbirth and maternity care services, meaning that women who carry pregnancies to term will still have to travel for prenatal services. Many of the prenatal clinics that do exist in the state’s remote areas are funded by federal Title X grant money, which has been under siege during the Trump administration. According to Chesney-Lind, the lack of reproductive health care access “is just adding one more burden to already challenged communities in those islands.”

The solution to Hawaii’s lack of services problem, says Chesney-Lind, is to shift the state’s energy away from the law and towards actual access. “There’s always a focus on keeping abortion legal, and women’s access has kind of taken a backseat to that issue,” she says. “I wish there was a similar kind of push to make sure that the services are provided on all the islands. That’s just missing.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Laurie Field as Laurie Graham.

Image credit: 4×6/Getty