Pikul Noorod/Shutterstock

There are a multitude of reasons why women get abortions. Maybe they already have children and can’t imagine being able to care for another one. They may not have a supportive partner and don’t want to be a single mother. They may be still in high school or simply don’t want a child. But research has shown that the most common reason women seek abortions is financial.

Although the socioeconomic status of women who choose to have abortions has been studied, a new study released Thursday in the American Journal of Public Health examines what happens to women who want abortions but are denied. The conclusion? Women who seek abortions but don’t receive them experience economic hardship in the years following the child’s birth.

“We see steady improvement over time for the women who receive an abortion,” said Diana Greene Foster, one of the study’s authors and a professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. “The other women are set back from the point of birth.”

In the study, which Foster told Mother Jones is the first of its kind, researchers followed more than 800 women who sought abortions at 30 abortion facilities across the country between 2008 and 2010. The study focused on women who had attempted to get the procedure either before or up to three weeks after the gestational age limit, the latest point in pregnancy permitted by the facility. After the women were either permitted or denied abortion services, researchers followed up with them, first one week later, and then every six months for five years.

Depending on state laws, facilities can have varying gestational limits: In Mississippi, a woman can only receive an abortion at or after 18 weeks if her life is in danger, while California has no abortion restrictions concerning gestation on the books. In her research, Foster said she encountered facilities with limits as early as 10 weeks (before the first trimester ends) and as late as more than 24 weeks (the very end of the second trimester). According to a 2016 report from the Guttmacher Institute, more than one-quarter of all abortion restrictions enacted since landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade occurred between 2011 and 2015. Foster said it’s possible that had the study been conducted after 2010, the sheer number of hurdles put into place to access an abortion provider would have led to more women being denied abortions and thus, experience worse economic fates.

The women in the study were divided into three groups: women who sought and obtained an abortion up to two weeks under the facility’s gestational limit; women who sought and were denied an abortion up to three weeks over the facility’s limit; and women who sought and received abortions during the first trimester, or during the first 14 weeks of gestation (Foster said this group may slightly overlap with the first group). Because some women in the “turnaway” group miscarried or received an abortion elsewhere after being denied, the group was further divided into “birth” and “no birth” subgroups. The main focus of the study, however, was comparing the first two groups in order to determine whether carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term changes economic circumstances.

The results for women forced to carry their pregnancies to term were bleak: They were more likely to be in poverty, less likely to have full-time employment, and more likely to receive public assistance for years later. Although women who were denied abortions slowly became more likely to have full-time employment, it took years for them to catch up to the women who had abortions.

There were no differences between groups in race, education, or marital status when the study began, but those who gave birth were more likely to be younger than 20 years old, less likely to already have children, and more likely to be unemployed. Foster said this is because young people and those who have never had children are more likely to not realize they’re pregnant until it’s too late to get an abortion.

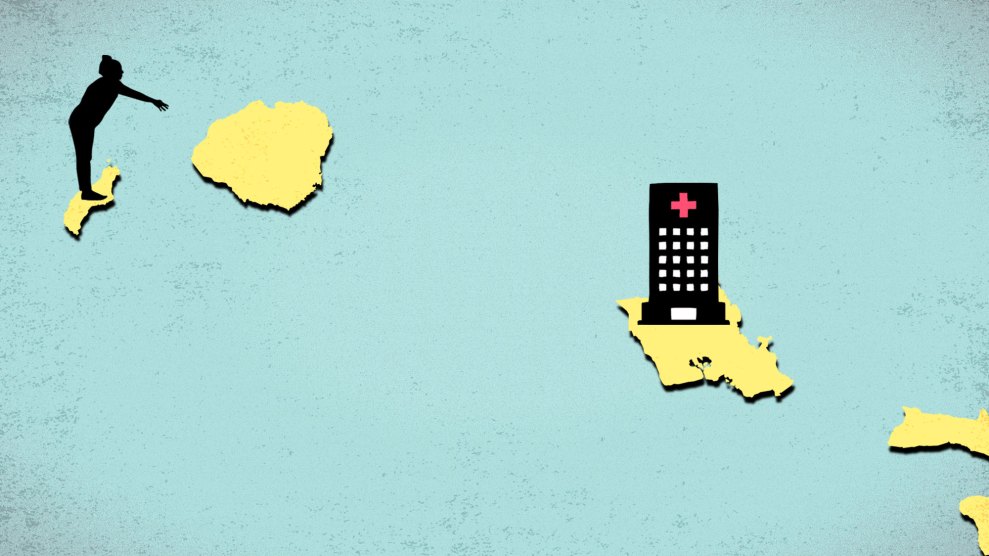

Kristyn Brandi, an abortion provider in Los Angeles County and a board member of Physicians for Reproductive Health, a reproductive rights advocacy organization, said that many women face problems of access, with abortion facilities located hundreds of miles from where they live. By the time these women made the arrangements to get to the facility, the gestational limit had passed. Being denied an abortion often doesn’t just impact the woman, she notes, and the financial consequences associated with denial can create a ripple effect that can take a toll on generations to come.

“We think about it as this one event, but these women are likely to be of reproductive age for years later, so it has repercussions for the children to come,” she told Mother Jones. “It has a big impact on our economy, and the economy of women.”