Noel Francisco is sworn-in to testify in his confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee in May 2017. Ron Sachs/picture-alliance/dpa/AP

Update: Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who oversees the Russia investigation, is on the verge Monday of resigning or being fired following a New York Times report that he discussed invoking the 25th Amendment to remove President Donald Trump from office and suggested wearing a wire to investigate the president. The person next in line to oversee the investigation into Russian interference is Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who has taken a skeptical view of special counsels.

The Justice Department official next in line to oversee Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian meddling in the 2016 election has expressed skepticism about the role of special counsels and made comments indicating he’s a fan of presidential power. These views could become important should President Donald Trump make a move to fire or rein in Mueller.

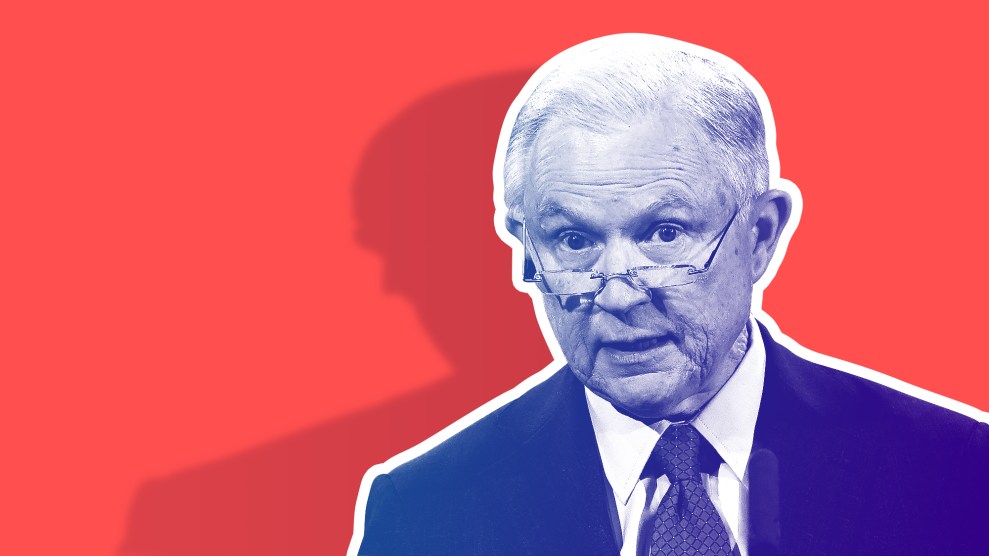

Since Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation last March, the probe has been overseen by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein. But as the investigation has churned on, Rosenstein has seemed to be on increasingly thin ice with President Trump, who has reportedly ruminated about firing him. Were Rosenstein ousted, oversight of the investigation would pass to the next most senior Justice Department official. Until recently, that would have been Rachel Brand, the associate attorney general. But she is stepping down—in part, according to NBC News, because she feared having to oversee the Russia inquiry—and no replacement has been named. That means, if Rosenstein were fired, Noel Francisco, the solicitor general, would inherit the high-profile case. Francisco, who is known within Washington legal circles as a conservative with a solid reputation, has not said anything publicly about the Russia investigation, but in the past he has dismissed the need for special counsels—saying career prosecutors are just as well equipped to look into possible White House wrongdoing—and he has said that executive privilege shields presidents from most investigations.

These comments came during congressional testimony and media interviews in 2007. At the time, George W. Bush’s Justice Department had come under intense congressional scrutiny for the dismissal of nine US attorneys. Congress was also investigating the Bush administration’s creation of a warrantless surveillance program and the Justice Department’s infamous memos justifying the administration’s use of brutal interrogation practices. Having previously served alongside Attorney General Alberto Gonzales in the Bush White House, Francisco, then in private practice, frequently made public appearances to defend the administration, which was accused of meddling in criminal prosecutions for political reasons and which resisted providing information related to the US attorneys scandal to Congress.

In a House judiciary subcommittee hearing on executive branch accountability in March 2007, Francisco weighed in on calls to appoint a special counsel to probe the US attorneys controversy. “I don’t think it would be appropriate for the Department of Justice to appoint” a special counsel, he testified, explaining that “my own personal belief is that when you hand these issues off to the career prosecutors in the public integrity sections in the US attorneys’ offices in the Department of Justice, those attorneys are generally better able to assess whether a case should be pursued.”

Francisco also testified that a president could invoke executive privilege to withhold information from a congressional probe, including shielding communications between his advisers from scrutiny. But he acknowledged that privilege could potentially be overridden by a criminal investigation. In such a case, he said, a president could still claim executive privilege. But, he added, a court could decide if a special counsel or prosecutor’s request trumped the executive privilege claim: “What the courts have said is that in the context of a criminal investigation, if there is a sufficient showing of need, it can obviate the privilege. We would be into the balancing world…that the Supreme Court employed in the Nixon case.” (He was referring to the case in which the Supreme Court forced President Richard Nixon to hand over the Watergate tapes to the special prosecutor investigating that scandal.)

If Rosenstein were dismissed—or recused himself—and the associate attorney general slot remained vacant, Francisco would have the ability to shape Mueller’s investigation. His philosophy on executive privilege could be important. He could decide the president’s right to keep secret the deliberations of his advisers supercedes the special counsel’s need for certain White House records. Or, more dramatically, he could remove Mueller if he believes the special counsel had violated Justice Department policy or shut down the investigation if he determines it should not continue. He could also undermine the inquiry in more subtle ways, limiting the scope of the probe by blocking lines of inquiry he deems outside of Mueller’s mandate. In fact, saddling Mueller with a boss hostile to the investigation, loyal to Trump, or simply no fan of special counsels, could be far worse for the Russia investigation than simply removing Mueller and letting rank-and-file FBI agents continue the probe.

The US attorneys scandal has echoes in the Russia investigation, particularly the firing of FBI Director James Comey last May. The president has the authority to remove FBI directors and US attorneys. But doing so to influence a prosecution is potentially illegal and, just as important, violates the norm that criminal investigations remain free from political interference. In the US attorneys scandal, the Justice Department’s inspector general found that the department’s leaders had “abdicated their responsibility to ensure that prosecutorial decisions would be based on the law, the evidence, and Department policy, not political pressure.”

But at the time, Francisco repeatedly argued the firings were appropriate and that the president has the authority to hire and fire US attorneys as he pleases. “The appointment and removal of United States attorneys is a quintessential and non-delegable presidential power,” he said in the 2007 hearing. “United States attorneys are political appointees who may be removed by the president for any reason— good or bad—or for no reason at all.” A spokeswoman for the solicitor general’s office declined to comment for this story.

Francisco also argued for a broad interpretation of executive power when it came to the Bush administration’s green lighting of torture and warrantless surveillance. (Francisco, who served in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel following his White House stint, reviewed one of the 2005 torture memos that okay’d waterboarding and other torture techniques.) “Since September 11, there have been no more attacks on this country,” he told US News & World Report in April 2007. “Those of us sitting here today have the luxury of believing it is still September 10. The president and the attorney general don’t have that luxury.”

Francisco’s past remarks suggest he might not be keen to support a robust special counsel investigation, particularly one that scrutinizes the actions of the president and his advisers. And there’s little in the record from Francisco’s confirmation testimony last May to counter such an assumption. After Comey was fired, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) asked Francisco, in a written questionnaire, whether it was “proper for the President to pressure a law enforcement official to terminate an ongoing investigation into one of the President’s associates?” Francisco declined to answer.