1. “I can’t stand lying to you every day”

In the late summer of 2015, Chris Wilson, the director of research, analytics, and digital strategy for Sen. Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign, had a conversation with a contractor that left him furious. A widely respected pollster who had taken leave from his firm to work full time for Cruz, Wilson oversaw a team of more than 40 data scientists, developers, and digital marketers, one of the largest departments inside Cruz’s Houston-based operation. The Iowa caucuses were fast approaching, and the Cruz campaign had poured nearly $13 million into winning the opening contest of the primary season.

RELATED: Undercover Video Captures Trump Campaign’s Data Firm Discussing Entrapping Politicians With Sex

As the campaign laid the groundwork for Iowa, a sizable chunk of its spending—$4.4 million and counting—flowed to a secretive company with British roots named Cambridge Analytica. A relative newcomer to American politics, the firm sold itself as the latest, greatest entrant into the burgeoning field of political technology. It claimed to possess detailed profiles on 230 million American voters based on up to 5,000 data points, everything from where you live to whether you own a car, your shopping habits and voting record, the medications you take, your religious affiliation, and the TV shows you watch. This data is available to anyone with deep pockets. But Cambridge professed to bring a unique approach to the microtargeting techniques that have become de rigueur in politics. It promised to couple consumer information with psychological data, harvested from social-media platforms and its own in-house survey research, to group voters by personality type, pegging them as agreeable or neurotic, confrontational or conciliatory, leaders or followers. It would then target these groups with specially tailored images and messages, delivered via Facebook ads, glossy mailers, or in-person interactions. The company’s CEO, a polo-playing Eton graduate named Alexander Nix, called it “our secret sauce.”

As a rule, Nix said his firm generally steered clear of working in British politics to avoid controversy in its own backyard. But it had no qualms applying its mind-bending techniques to a foreign electorate. “It’s someone else’s political system,” explains one former Cambridge employee, a British citizen. “It’s not ours. None of us would ever consider doing what we were doing here.”

Brought to Cruz by two of the campaign’s biggest backers, hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer and his daughter Rebekah, Cambridge Analytica was put in charge of the entire data and digital operation, embedding 12 of its employees in Houston. The company, largely owned by Robert Mercer, said it had something special for Cruz. According to marketing materials obtained by Mother Jones, it pitched a “revolutionary” piece of software called Ripon, an all-in-one tool that let a campaign manage its voter database, microtargeting efforts, door-to-door canvassing, low-dollar fundraising, and surveys. Ripon, Cambridge vowed, was “the future of campaigning.” (The name is a clever bit of marketing: Ripon is the small town in Wisconsin where the Republican Party was born.)

The Cruz campaign believed Ripon might give it an edge in a crowded field of Republican hopefuls. But the software wasn’t ready right away. According to former Cruz staffers, Wilson inquired about Ripon’s status daily. It was almost finished, he was repeatedly told. Weeks passed, then months. Finally, in August 2015, one of the Cambridge consultants in Houston came clean. Ripon “doesn’t exist,” he told Wilson, according to several former Cruz staffers. “It’ll never exist. I’ve just resigned because I can’t stand lying to you every day anymore.” The campaign had hired Cambridge in the belief it could use Ripon to help win Cruz the nomination; instead, it was paying millions of dollars to build the Ripon technology. “It was like an internal Ponzi scheme,” a former Cruz campaign official told me.

The Cruz campaign couldn’t fire Cambridge outright. The Mercers wouldn’t be happy, and the campaign was too far along to ax a significant part of its digital staff. Still, Cruz officials steadily reduced Cambridge’s role. Even though the campaign used Cambridge’s psychological data in Iowa, Cruz’s victory there in February 2016 did nothing to quell the growing distrust campaign officials felt toward the company.

The Cruz team wasn’t alone in its doubts about the firm. Cambridge was also working, albeit in a more limited role, for rival Ben Carson’s campaign, whose experience with the company was similarly frustrating. Cambridge, for instance, sold itself as an expert in TV advertising yet failed to grasp basic facts about buying ads. Carson staffers came away feeling like Cambridge was at best in over its head and at worst a sham.

After Carson and Cruz dropped out and Trump all but clinched the nomination, Doug Watts, a senior staffer on the Carson campaign, got a call from Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign chairman. “What do you know about Cambridge Analytica?” Manafort asked.

Watts replied that he didn’t think much of the firm. “They’re just full of shit, right?” Manafort said, according to Watts. “I don’t want ’em anywhere near the campaign.”

A few months later, on September 19, 2016, Alexander Nix strode onstage at the Concordia Annual Summit in Manhattan, a highbrow TED-meets-Davos confab. He was a featured speaker alongside Madeleine Albright, Warren Buffett, David Petraeus, and New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand. Wired magazine had recently named him one of its “25 Geniuses Who Are Creating the Future of Business.”

In a dark tailored suit and designer glasses, wearing a signet ring on his left pinkie, Nix regaled the audience with the story of how Cambridge Analytica had turned Ted Cruz from an obscure and reviled US senator into “the only credible threat to the phenomenon Donald Trump.” Using Cambridge’s methods, the Cruz campaign had sliced and diced Iowa caucus-goers into hyperspecific groups based on their personality traits and the issues they cared about, such as the Second Amendment. As Nix clicked through his slides, he showed how it was possible to use so-called psychographics—a fancy term for measuring attitudes and interests of individuals—to narrow the universe of Iowans from the tens of thousands down to a single persuadable voter. In this case, Nix’s slide listed a man named Jeffrey Jay Ruest, a registered Republican born in 1963. He was “very low in neuroticism, quite low in openness, and slightly conscientious”—and would likely be receptive to a gun rights message.

“Clearly the Cruz campaign is over now,” he said as he finished his presentation, “but what I can tell you is that of the two candidates left in this election, one of them is using these technologies, and it’s going to be very interesting to see how they impact the next seven weeks.”

That candidate was Donald Trump. After Cruz dropped out in May 2016, the Mercers had quickly shifted their alliance to Trump, and his campaign hired their data firm over Manafort’s apparent objections. “Obviously he didn’t bargain for Rebekah Mercer being their big advocate,” Watts says. “So I presume he just capitulated.” Soon Trump jettisoned Manafort and installed in his place the Mercers’ political Svengali, Steve Bannon, who was also a board member, vice president, and part-owner of Cambridge Analytica.

Come November 9, 2016, Cambridge wasted no time touting itself as a visionary that had seen Trump’s path to the White House when no one else did. Nix took an international victory lap to drum up new political business in Australia, India, Brazil, and Germany. Another Cambridge director gushed that the firm was receiving so much client interest that “it’s like drinking from a fire hose.”

Actually, the 2016 election was the high-water mark for Cambridge Analytica. Since then, the firm has all but vanished from the US political scene. According to Nix, this was by design. Late last year, he said his company had ceased pursuing new US political business. But recently, an extraordinary series of developments unfolded that led to Nix’s suspension as CEO and left the company’s future uncertain. A whistleblower went public with allegations, since cited in a class-action lawsuit, that the company had used unethical methods to obtain a massive trove of Facebook data to fuel its psychographic tactics.

“We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons,” Chris Wylie, who helped launch the company, told the British Observer. “That was the basis the entire company was built on.” Next came the release of an undercover investigation by the United Kingdom’s Channel 4, which captured video of Nix and other Cambridge executives explaining how they could covertly inject propaganda “into the bloodstream to the internet.” They also described how their services could include bribing a politician and recording undercover video or sending “very beautiful” Ukrainian “girls” to entrap a candidate.

The fallout was swift. Facebook, already under fire for facilitating the spread of disinformation, suspended Cambridge from its platform. British officials sought a warrant to search the company’s office. Lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic demanded answers. “They should be barred from any US election or government work until a full investigation can be conducted,” Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas), a member of the House Intelligence Committee, tweeted.

The story of Cambridge Analytica’s rise—and its rapid fall—in some ways parallels the ascendance of the candidate it claims it helped elevate to the presidency. It reached the apex of American politics through a mix of bluffing, luck, failing upward, and—yes—psychological manipulation. Sound familiar?

Like Trump, Nix was a master of hype who peddled a story that people wanted to believe. Take Jeffrey Ruest, the voter Nix identified at the Concordia Summit, down to the latitude and longitude of his home, to illustrate the firm’s psychographic prowess in Iowa. The message was that Cambridge had the ability to peer into the minds of—and to persuade—voters on the most granular level. Ruest wouldn’t have been useful to Cruz or any of his GOP rivals in Iowa, though. He lives a thousand miles away in North Carolina. But why let inconvenient details interfere with the perfect pitch?

2. “We called him Mr. Bond”

“We use the same techniques as Aristotle and Hitler,” the consultant said. “We appeal to people on an emotional level to get them to agree on a functional level.”

The year was 1992. The consultant was Nigel Oakes, a former Monte Carlo TV producer and ad man for Saatchi & Saatchi, and he was speaking to the trade magazine Marketing. Oakes was then running the Behavioural Dynamics Institute, a “research facility for understanding group behaviour” and for harnessing the power of psychology to craft messages that change hearts and minds. But in reality, Oakes’ institute was a stalking horse for the company he would launch the year after the interview.

Strategic Communication Laboratories, the public affairs company that would later spawn Cambridge Analytica, began small, applying its behavioral-science-minded approach to public influence campaigns in the United Kingdom, including one that, it boasts, rescued Lloyd’s of London by convincing Britons to invest another $1.5 billion in the ailing insurance market. But SCL soon branched into politics. Oakes says he advised Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress on how to prevent violence during the 1994 elections, as well as politicians in Asia, South America, and Europe. In 2000, the government of Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid, who was struggling to contain the violence and upheaval in his country, hired Oakes to burnish his image, which involved building an elaborate media command center in Jakarta for monitoring and shaping public sentiment. “We called him Mr. Bond because he is English,” one of Oakes’ Indonesian employees told the Independent, “and because he is such a mystery.”

Data expert Alexander Nix, CEO of Cambridge Analytica

Mother Jones illustration

In 2005, SCL expanded into military and defense, pitching the use of “psychological operations” and “soft power” in the war on terror. The firm began picking up major clients, including the Pentagon and the UK Ministry of Defense, advising them on which Afghan leaders to target with counterinsurgency messages or how to dissuade teenage boys from joining Al Qaeda.

The company had meanwhile hired Nix, a former financial analyst, to grow its nondefense business. Former colleagues say he was just the man for the job. “Nix the salesman is an artist, to be honest,” one told me. Another referred to him as a “chancer,” the British term for a consummate opportunist. “He’ll always be like, ‘Can I give it a go?’” the colleague said. “‘Can I sell this to you and work out the details afterward?’”

Nix had an eye on the United States, where the courts were stripping away restrictions on political spending and empowering a new class of individual megadonors. He traveled here in 2010 to get the lay of the land but came away discouraged. Political consultants picked sides in America, he learned. A British outfit that worked with both left- and right-of-center clients might struggle to break into the market.

Then, on Election Day in November 2012, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney watched as his campaign’s voter-turnout app, code-named Project Orca, crashed. It was humiliating but indicative of a larger dynamic: Democrats, powered by President Barack Obama’s 2008 and 2012 runs, had gained a huge advantage over their Republican counterparts in the realms of data and technology. The GOP’s 2012 postmortem report called for a cultural shift inside the party to embrace new tools and methodologies to win. “We have to be the Party that is open and ready to rebuild our entire playbook,” it read, “and we must take advice from outside our comfort zone.”

Nix saw his opening. SCL had recently rebranded itself as an expert in data analytics, the sifting and distilling of vast amounts of information from different sources into actionable outcomes. That skill set, combined with SCL’s previous work in microtargeting and psy-ops, made it an ideal candidate to find an audience in the world of Republican politics. “The Republicans had been left behind,” Nix later said. “By the time Romney lost in 2012, there was a vacuum. And so that was the commercial opportunity.”

Nix was soon introduced to Chris Wylie, then a twentysomething Canadian technologist. Wylie had worked under Obama’s director of targeting and consulted for Canada’s Liberal Party. Nix hired him and put him to work building a company that could attract clients in the hypercompetitive US political market. Wylie, for his part, had an idea about how his new employer, SCL, might gain an edge.

In 2007, David Stillwell, then a Ph.D. student in psychology, stumbled onto a digital gold mine. He’d always wondered about his personality and how he would score in the five-factor model, a personality test that measures openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Known as Ocean, this model is widely used by psychologists. But one challenge they encountered when applying it to different areas—marketing, relationships, politics—was gathering sufficient data. People naturally hesitate to give personal information about their fears, desires, and motivations.

Stillwell knew a little code, so he pulled certain Big Five questionnaires off the internet, stuck them in a quiz format, and uploaded an app to Facebook called myPersonality. It quickly went viral. Millions of people took the quiz, and with their permission, Stillwell went on to accumulate data on personality traits and Facebook habits for 4 million of them.

Using this data, Stillwell, now working at the University of Cambridge’s Psychometrics Centre, and two other researchers published a paper in 2013 in which they showed how you could predict an individual’s skin color or sexuality based on her Facebook “likes.” They found a correlation between high intelligence and likes of “thunderstorms,” “The Colbert Report,” and “curly fries,” while users who liked the Hello Kitty brand tended to be high on openness and lower on conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability.

Stillwell told me that as an afterthought, he and his co-authors threw in some language at the end about the commercial possibilities of their findings. The paper attracted the attention of companies looking to leverage Facebook and other social-media data for their own purposes. One person who took a keen interest was SCL’s Chris Wylie.

According to emails obtained by Mother Jones, Wylie approached Stillwell and a colleague via a fellow faculty member, a young Russian American professor named Aleksandr Kogan, hoping to cut a deal in which the firm would get access to Stillwell’s data.

Stillwell hadn’t heard of SCL. But he agreed to a meeting. When dates were circulated between the Cambridge academics and the SCL representatives, the title wasn’t subtle: “Panopticon meeting.” (Panopticon refers to a prison or building constructed so that all parts of it are visible by a single watchman but the surveilled can’t see who’s viewing them.) In the end, Stillwell decided not to partner with SCL.

Undeterred, SCL instead hired Kogan, who went on to create his own Facebook app, “thisisyourdigitallife.” As detailed in a class-action suit against Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, the app—which purported to be for academic research—not only collected personality data on the 270,000 people who took the quiz but also let Kogan vacuum up Facebook user data on all their friends. The Washington Post reported in late March that Facebook separately provided Kogan with data on 57 billion friendships as part of his work with two of the company’s data scientists between 2013 and 2015. Around the same time he was mining Facebook data, Kogan also forged a relationship with Saint Petersburg University, which hired him as an associate professor and provided him with research funding. He denies this research had any connection to his work for SCL.

According to Wylie, Kogan acquired more than 50 million profiles. He says Kogan then passed that data to SCL—in apparent violation of Facebook’s terms of use—in order to build its psychographic profiling methods. “Everyone knew we were wading into a gray area,” Wylie later said. “It was an instance of if you don’t ask questions, you won’t get an answer you don’t like.” (Kogan denies any wrongdoing: “My view is that I’m being basically used as a scapegoat.”)

Nix now had his calling card. SCL would break into the $10 billion American political market by pitching itself as a “cutting-edge” consultancy using “behavioral microtargeting”—that is, influencing voters based not on their demographics but on their personalities—and sophisticated data modeling to win elections. His timing couldn’t have been better.

3. “Marketing materials aren’t given under oath.”

One day in 2013, a knockabout Republican political consultant named Mark Block and his colleague boarded a flight from Los Angeles to New York. As the plane took off, they got to talking with the man seated next to them, an ex-military officer who mentioned he worked as a subcontractor for a company seeking US political clients. “They do cyberwarfare for elections,” the subcontractor said. Block dozed off as his colleague and her seatmate continued to chat. When they landed, his colleague told him excitedly that they needed to talk to a guy named Alexander Nix.

Not long after, they met with Nix in a conference room in the Willard InterContinental hotel, a stone’s throw from the White House. The meeting lasted more than six hours, Block recalls, as Nix described how they could use personality data and psychographics in American campaigns. “By the time he was done, I’m going like, ‘Holy shit,’” Block told me. “I had been aware of what Obama had done…But this seemed to be light-years ahead.”

At a subsequent meeting Block attended, Nix was introduced to Rebekah Mercer, who was quickly becoming one of the biggest donors in Republican politics. Bekah, as she’s known to friends, is the middle daughter of Robert Mercer, a billionaire computer scientist who pioneered the use of algorithms in investing at the Long Island-based hedge fund Renaissance Technologies. Bekah is the political animal of the Mercer family, and in the late 2000s and early 2010s she plowed $35 million from her family foundation into conservative groups such as the Heritage Foundation, the Federalist Society, and the Heartland Institute. The Mercers also invested a reported $10 million in Breitbart News in 2011. They’ve donated millions to Republican candidates and super-PACs, from Mitt Romney and Herman Cain to a congressional candidate in Oregon named Arthur Robinson, who caught Robert Mercer’s attention with a pseudoscientific newsletter in which he argued that small amounts of nuclear radiation have health benefits.

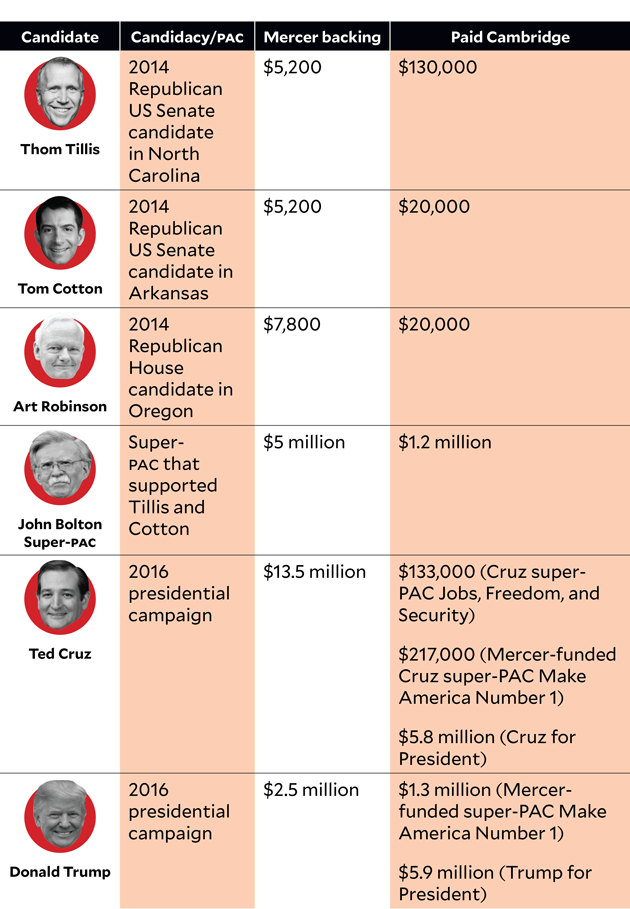

Quid Pro Mercer

How the megadonors have leveraged their political spending into profits for their data firm

The Mercers had attended the semiannual donor retreats organized by Charles and David Koch and had, according to a source familiar with their political work, invested in the Kochs’ data venture, Themis (named for the Greek goddess of wisdom and order), which was supposed to close the gap with Democrats in the data arms race. But after Romney’s loss in 2012, the Mercers were fed up. Bekah Mercer turned heads at a 2012 postmortem event at the University Club in Manhattan when she excoriated the Romney campaign for its lackluster data operation. According to people familiar with the Mercers’ thinking, Bekah and her father set out to find their own data geniuses.

Over lunch in Manhattan, Bekah listened intently as Nix gave his pitch. When he finished, she said, “I really want you to tell this to my dad.” She gave him an address with instructions to meet later that day. At the appointed time, Nix and Block arrived at a grungy sports bar on the Hudson River, north of the city. “We’re going like, ‘What the fuck?’” Block says. Bekah texted to say she and her father would soon arrive. Moments later, Sea Owl, the Mercer family’s 203-foot superyacht, pulled up to the dock behind the sports bar.

Aboard the yacht, Nix took a seat next to Robert Mercer, opened his Mac, and launched into his spiel again. Bekah sat next to her father on the couch. Behind them stood Steve Bannon, the investment banker turned Hollywood producer and conservative activist who took over Breitbart News after the death of Andrew Breitbart. Whatever Nix told the Mercers that day in 2013, it worked: They agreed to invest a reported $15 million in a new company that would be the face of SCL’s American political work. Bannon was given a seat on the board and a stake in the new company to help, as Nix later said, the firm navigate the US political scene. Nix installed himself in Mercerworld, presenting himself as Bekah Mercer’s political guru and taking meetings at the Breitbart Embassy, the Capitol Hill row house that served as the conservative website’s offices and Bannon’s crash pad. The company was incorporated in Delaware on December 31, 2013. The name was a mix of old and new: Cambridge Analytica.

But if the Mercers had paid closer attention to a test run of Nix’s venture in the 2013 Virginia governor’s race, they might have reconsidered going into business with SCL. A PAC, the Middle Resolution, had paid Nix’s company several hundred thousand dollars that year for a list of persuadable voters to help elect Republican Ken Cuccinelli, who was running for governor. Months passed, and the list never arrived. When the group’s founder, Bob Bailie, demanded the list, Nix asked for more money and Bailie cut bait. Another Virginia-based group, Americans for Limited Government, then paid SCL $100,000 to create a list of suburban female voters who traditionally supported Democrats but might be swayed to vote for Cuccinelli if shown the right message. Late in the race, the group’s canvassers took Nix’s list into the field and returned with a perplexing result: The people on it were already Cuccinelli supporters. The higher-ups at Americans for Limited Government asked another firm to analyze the list. It turned out SCL had handed them a roster of die-hard Republicans.

Despite these early missteps, Cambridge Analytica quickly signed on a host of new clients thanks to the Mercers, who leveraged their position as megadonors to effectively strong-arm politicians into using their new firm. “It was the Mercers that made people work with us,” an early Cambridge employee told me. Cambridge boasted eight clients at the federal level in 2013 and 2014, and members of the Mercer family have supplied financial backing to each of them, including to five during that election cycle. One was former Ambassador John Bolton’s super-PAC, a potential vehicle for a presidential run. During the 2014 midterms, Robert Mercer gave $1 million to the group, which soon paid Cambridge more than $340,000 to develop Cambridge’s personality-based targeting on the issue of national security. It was an odd arrangement: Recipients of Mercer money would turn around and pay a vendor partly owned by the Mercers. (Rebekah Mercer did not respond to requests for comment.)

Cambridge Analytica’s work in the 2014 midterms received mixed reviews. A consultant for Thom Tillis’ US Senate race in North Carolina singled out for praise a Cambridge contractor who had embedded with the campaign. But in other instances, the firm’s seemingly weak grasp of American politics turned off operatives. Once, a Cambridge employee appeared unaware what a precinct was. In another case, according to a prominent Republican consultant, Cambridge proposed influencing Republican voters living overseas by creating a model that targeted all absentee voters, suggesting that the firm didn’t realize that people who live in the United States can also vote absentee.

The most common criticism I heard about Nix was that he habitually overpromised and underdelivered. According to a person who worked with him, Nix had a saying: “Marketing materials aren’t given under oath.” (Nix, Cambridge, and SCL did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this story.)

But Nix and his company used their work helping to elect Tillis and another Mercer-backed candidate, Tom Cotton of Arkansas, as a steppingstone. Cambridge explored new corporate clients, pitching the Colorado-based DISH Network. (“DISH does not have, nor has it ever had, a business relationship with Cambridge Analytica,” a spokesman said.)

Perhaps inspired by Bannon, whom Wylie described to the Washington Post as “Nix’s boss,” the company began testing messages designed to tap into immigration fears, anti-government sentiment, and an affinity for strongmen—“build the wall,” “drain the swamp,” “race realism” (a euphemism for rolling back civil rights protections). It also surveyed opinions about Russian President Vladimir Putin. It seemed as if they were getting ready for a presidential campaign—but which one?

4. “They’ve gotten the wool pulled over their eyes”

At 8:05 p.m. on March 22, 2015, Ted Cruz’s personal Twitter account posted a message: “Tonight around midnight there will be some news you won’t want to miss. Stay tuned…” There wasn’t much suspense—Cruz had effectively launched his presidential bid the day he arrived in the Senate two years earlier, but now he would make it official.

At midnight, the senator’s team in Houston would turn on the campaign website built by Cambridge Analytica. Then, at 12:01 a.m.…nothing. “We couldn’t even get the website up,” one former Cruz staffer told me. Eight excruciating minutes passed before Cruz simply sent another tweet: “I’m running for President and I hope to earn your support!”

It was a harbinger of things to come. Interviews with eight people who worked on the Cruz campaign reveal a litany of disputes with Nix. As the campaign’s frustrations mounted, it winnowed the number of Cambridge staffers in Houston from 12 to 3.

Cruz’s campaign did, however, employ Cambridge’s psychographic models, especially in the run-up to Iowa. According to internal Cambridge memos, the firm devised four personality types of possible Cruz voters—“timid traditionalists,” “stoic traditionalists,” “temperamental” people, and “relaxed leaders.” The memos laid out how the campaign should talk to each group about Cruz’s marquee issues, such as abolishing the IRS or stopping the Iran nuclear deal. A timid traditionalist, the memo said, was someone who was “highly emotional” but valued “order and structure in their lives.” For this kind of person, an “Abolish the IRS” message should be presented as something that “will bring more/restore order to the system.” Recommended images included “a family having a nice moment together, with a smaller image representing Washington off to the side—representing that a small state makes for better private moments.” But for a temperamental type, the suggested image was a “young man tossing away a tax return and taking the key of his motorbike to head out for a ride.”

Almost two months before the Iowa caucus, the Guardian reported that Cambridge and the Cruz campaign were using unauthorized Facebook data—an early indication of what Chris Wylie would later reveal in full. In response, Facebook told Cambridge to delete any Facebook data it held. Wylie says that while he deleted the data in his possession, he merely filled out a form and sent it back to Facebook certifying that he’d deleted the information. Facebook, he adds, never verified whether he actually had. A former Cruz staffer told me that well after the Guardian report, he could still use Cambridge’s Facebook data to build voter models.

The Cruz campaign eked out a victory in Iowa, and Nix was quick to take credit during an interview on Fox News. Whether Cambridge’s psychographics played any part in Cruz’s win is debatable: When the firm began using these techniques on December 1, two months before the caucus, Cruz was polling at 28 percentage points in Iowa. From there to caucus day, his numbers fluctuated in the range between 23 and 32 percent. Contrary to Nix’s claim that Cruz was languishing in the single digits until Cambridge came along, the candidate was already well on his way to winning when Cambridge’s secret sauce kicked in. “If we weren’t using the personality stuff until that point in time,” a former Cruz official says, “then Nix can’t credibly make the argument that it mattered, right?”

Adding to suspicions about whether Cambridge’s personality profiling worked as claimed was the fact that the company refused to share any of its underlying models. Cambridge advised the campaign on how best to deliver Cruz’s message to “stoic traditionalists” and “relaxed leaders,” but it wouldn’t divulge how it came up with those personality types in the first place. “They’re the least transparent company in the business,” a former Cruz staffer told me. Nor did Cambridge seem to understand the fundamentals of how a presidential campaign operated: Two weeks out from the South Carolina primary, Cruz’s data team discovered that the company hadn’t updated the voter database feeding its models in seven months. The result: In a primary where the victory margin could be in the low thousands, there were 70,000 people Cruz wasn’t targeting because his data was stale. “How fucked up is that?” the former Cruz staffer told me. “That’s political malpractice.” Cruz finished third in South Carolina. After the opening four states, he stopped using Cambridge’s personality-profiling models.

The company’s lackluster performance on the Cruz campaign didn’t stop Nix from walking onstage at the Concordia Summit and taking credit for Cruz’s second-place finish in the nomination fight. Word of his speech spread in Cruz circles, and campaign alums watched the video of Nix and scoffed. “Most of that’s bullshit or things we designed on the campaign,” one senior Cruz staffer told me. “Everybody has respect for the Mercers. But they’ve gotten the wool pulled over their eyes.”

5. “The phenomenon Donald Trump”

The Cruz campaign was still in the process of unwinding when Cambridge, following the lead of its investors, the Mercers, offered its services to the Trump campaign. Cambridge had previously reached out to Trump’s team, but his advisers didn’t want to hire the firm if it was also working for his rivals. Now, this was no longer an issue. Nix sent three employees to Texas to meet with Brad Parscale, Trump’s head of digital operations, who had no political experience and had gotten to know the Trump family while building websites for their company. (Parscale was recently named Trump’s 2020 campaign manager.)

As Nix courted the Trump campaign, he came up with an idea to boost the GOP nominee-in-waiting—one that was more in line with the political dirty tricks he and his colleagues would later discuss with Channel 4’s undercover reporter. WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange had recently told a British TV station that he had come into possession of internal emails belonging to senior Clinton campaign officials—the result of a cyberattack later revealed to be the work of Russian hackers. Nix reached out to Assange via his speaking agency, seeking a meeting. Nix reportedly hoped to get access to the emails and help Assange share them with the public—that is, he wanted to weaponize the information. According to both Nix and Assange, the WikiLeaks founder passed on his offer.

RELATED: A Groundbreaking Case May Force Controversial Data Firm Cambridge Analytica to Reveal Trump Secrets

Nevertheless, by late June Nix had landed a contract with the Trump team. At first, a handful of Cambridge employees set up shop in San Antonio, where Parscale was running Trump’s digital operation out of his marketing firm’s offices. But Matt Oczkowski, Cambridge’s head of product, was eventually put in charge of the San Antonio office after Parscale relocated to campaign headquarters in Trump Tower.

What exactly Cambridge Analytica did for Trump remains murky, though in the days after the election, Nix’s firm blasted out one press release after another touting the “integral” and “pivotal” role it played in Trump’s shocking upset. Nix later told Channel 4’s undercover reporter that Cambridge deserved much of the credit for Trump’s win. “We did all the research, all the data, all the analytics, all the targeting. We ran all the digital campaign, the television campaign, and our data informed all the strategy,” he said. Another Cambridge executive suggested the firm had delivered Trump victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—states crucial to his ultimate win. “When you think about the fact that Donald Trump lost the popular vote by 3 million votes but won the Electoral College vote, that’s down to the data and the research.”

Cambridge helped run an anti-Hillary Clinton online ad campaign for a Mercer-funded super-PAC that paid the company $1.2 million. The ads stated that Clinton “might be the first president to go to jail” and echoed conspiracy theories about her health. But according to multiple Republican sources familiar with Cambridge’s work for Trump, the firm played at best a minor role in Trump’s victory. Parscale has said that $5 million of the $5.9 million the Trump campaign paid Cambridge was for a large TV ad buy. When Cambridge bungled that—some of the ads wound up running in the District of Columbia, a total waste of money—the firm was not used for future ad buys. During an interview with 60 Minutes last fall, Parscale dismissed the company’s psychographic methods: “I just don’t think it works.” Trump’s secret strategy, he said, wasn’t secret at all: The campaign went all-in on Facebook, making full use of the platform’s advertising tools. “Donald Trump won,” Parscale said, “but I think Facebook was the method.”

Nix, however, seemed determined to capitalize on Trump’s victory. Cambridge opened a new office a few blocks from the White House, where Bannon would soon take on his new role as Trump’s chief political strategist. (Bannon retained his stake in the firm, valued between $1 million and $5 million, until April 2017, months after Trump took office.) SCL, its UK-based affiliate, eventually relocated its global headquarters from London to Arlington, Virginia, and began chasing government work, quickly landing a $500,000 State Department contract to monitor the impact of foreign propaganda. SCL briefly signed on Lt. General Michael Flynn as an adviser and later hired a former Flynn associate to run its DC office.

But even as Nix jetted around the globe and Cambridge opened new offices in Brazil and Malaysia, the company found itself with few allies in the United States. Trump campaign alums and Republican Party staffers distanced themselves from the company—especially after news broke last October that Nix had communicated with Assange. “We were proud to have worked with the RNC and its data experts and relied on them as our main source for data analytics,” Michael Glassner, the Trump campaign’s executive director, said in a statement released in response to these reports. “Any claims that voter data from any other source played a key role in the victory are false.”

By late 2017, after giving every indication that Cambridge Analytica intended to be a major player in American politics, Nix told Forbes the firm was no longer “chasing any US political business,” a decision he framed as a strategic move. “There’s going to be literally dozens and dozens of political firms [working in 2018], and we thought that’s a lot of mouths to feed and very little food on the table.” This seemed dubious—working on a winning presidential race is a golden ticket that most consultants would dine out on for years. In reality, Cambridge Analytica’s reputation for spotty work had circulated widely among Democratic and Republican operatives, who were also put off by Nix’s grandstanding and self-promotion. Mark Jablonowski, a partner at the firm DSPolitical, told me that there was “basically a de facto blacklist” of the firm and “a consensus Cambridge Analytica had overhyped their supposed accomplishments.” Perhaps even worse for a company that had relied on its billionaire patrons to open doors to new clients, the Mercers ceased “flogging for” Cambridge, according to Doug Watts, the former Ben Carson staffer.

For any upstart company, this would have constituted a crisis. But being shunned from the American political scene, it turned out, was just the start of Cambridge’s problems.

6. “I am aware how this looks”

Nix was near his London office when a Channel 4 correspondent confronted him. “Have you ever used entrapment in the past?” the reporter asked, thrusting a microphone in Nix’s face. “Is it time for you to abandon your political work?”

Captured on tape musing about entrapment and spreading untraceable propaganda, accused of misappropriating Facebook data to meddle with the minds of American voters—by March 20, scandal had reached Nix’s doorstep. He brushed past the reporter and into his building.

“I am aware how this looks,” Nix said in a statement. He explained that the explosive comments he and his colleagues had made to an undercover reporter were untrue. They were just “playing along” with “ludicrous hypothetical scenarios” proposed by a prospective client. His company, meanwhile, claimed that it did not “use or hold data from Facebook profiles.” By the end of the day, Cambridge Analytica had suspended Nix pending an investigation, and he had offered to resign if it would spare the company. “Alexander was always entertaining,” a former colleague told me. “In the end, he will always hang himself.”

The revelations about Cambridge Analytica’s alleged political tricks and shady data mining added to a growing list of problems the company was already facing. A few months earlier, in December, Nix had appeared before the House Intelligence Committee—though not in person. The panel’s Republicans, who ran the committee’s Russia probe with an eye toward minimizing any political damage to the president, arranged for Nix to beam in by video link. One topic of discussion was Nix’s outreach to WikiLeaks. His testimony remains secret, though he subsequently acknowledged approaching Assange in an effort to get his hands on “information that could be incredibly relevant to the outcome of the US election.” (In the Channel 4 undercover footage, Nix mocked the Intelligence Committee and said the Republican members asked him only three questions. “Five minutes—done,” he said, adding, “They’re politicians; they’re not technical. They don’t understand how it works.”)

From left: Rebekah Mercer, Christopher Wylie and Steve Bannon

Mother Jones illustration

The committee’s Democrats had taken a keen interest in Trump’s data operation and Cambridge Analytica’s role in particular. Michael Bahar, a former general counsel on the committee who worked on the investigation before entering private practice, told me that one line of inquiry explored whether Cambridge Analytica had deployed its targeting tactics to more effectively spread Russian disinformation, and whether it had been enlisted to use data and analytics stolen from the Democratic National Committee by Russian-directed hackers. “Maybe [hacked information] was actually given to a campaign to help with the microtargeting,” Bahar says. “That’s why I think the role of Cambridge Analytica…needs to be looked at very carefully.”

Scrutiny will likely intensify given revelations that Cambridge’s Russian connections predated the 2016 election. Wylie, the former Cambridge employee, provided documents to the Observer revealing that the firm briefed Lukoil, the Russian oil company, on its behavioral microtargeting strategies. In a recent interview with CNN, Wylie drew a startling connection between the firm’s work and the Russian cyberattacks during the election. “I am concerned that we made Russia aware of the programs that we were working on,” he said, “and that might have sparked an idea that eventually led to some of the disinformation programs that we have seen.”

In addition to Nix, Democrats, according to a House Intelligence Committee memo, had hoped to call as witnesses Alex Tayler, Cambridge Analytica’s chief data officer; Julian Wheatland, the chairman of SCL; and Rebekah Mercer. Instead, in early March, committee Republicans hastily shut down the probe, though Democrats have vowed to continue investigating on their own, although without subpoena power. On March 21, the committee’s ranking member, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), wrote to Aleksandr Kogan seeking an interview and requesting documents about his interactions with SCL and Cambridge Analytica. Chris Wylie has agreed to meet with committee Democrats.

The firm also remains a subject of interest to special counsel Robert Mueller’s team. According to the Wall Street Journal, Mueller last fall requested the emails of any Cambridge employee who worked on the Trump campaign. Nix’s unguarded comments to Channel 4 may be of interest. He said the firm relied on an encrypted email system that deleted messages two hours after they were read. “So then there’s no evidence, there’s no paper trail, there’s nothing.”

Yet another avenue of interest for investigators is Cambridge’s possible role in a second 2016 election that featured covert Russian meddling—the British referendum to leave the European Union, known as Brexit. In 2016, Cambridge seemed to break its informal rule of forgoing UK political work when it unveiled a partnership with Leave.EU, the more extreme of the pro-Brexit campaigns, only to backtrack and deny any involvement in Brexit.

In February, as part of a broader inquiry into fake news, members of the British Parliament’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee grilled Nix for more than two hours. He unconvincingly blamed the announcement of the Leave.EU partnership on “a slightly overzealous PR consultant.” He claimed that he and his staff had “never worked with a Russian organization in Russia or any other country.” And he denied that his firm used Facebook data. After the latest round of revelations, Damian Collins, a conservative member of Parliament who chairs the committee, said Nix had “deliberately misled” his panel “by giving false statements” and vowed to further investigate.

The blowback from the Cambridge Analytica scandals also hit Facebook, which faced a torrent of criticism for its lax handling of users’ data. The company’s stock price tumbled by 7 percent, losing more than $50 billion in value, and the Federal Trade Commission reportedly launched an investigation into its data practices. The hashtag #DeleteFacebook trended on Twitter. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg finally broke his silence, issuing a statement admitting to a “breach of trust” between Facebook and its users.

Yet, critics wondered, just how many times had their trust been breached? Cambridge Analytica was hardly alone in hoovering up user data. And how exactly were Cambridge Analytica’s psychographic techniques different from Facebook’s core business model—tapping into the vast amounts of data it collects on its users to guide hypertargeted advertising, be it for shoe companies or political campaigns or dubious fake news sites.

By most accounts, Cambridge Analytica’s main feat of political persuasion was convincing a group of Republican donors, candidates, and organizations to hand over millions of dollars. (A company called Emerdata that lists Nix as a director recently added Rebekah Mercer and another Mercer daughter to its board, suggesting that Nix hasn’t fallen out with all his GOP patrons.) But Cambridge’s controversial foray into US politics spawned larger questions about how our social-media habits can be turned against us, and how companies such as Facebook hold more power over our lives—the ability to shape public conversation, even political outcomes—than many people are comfortable with. Whether or not Cambridge Analytica survives, data about our personality types, our predilections, our hopes and fears—information we unwittingly divulge via status updates, tweets, likes, and photos—will increasingly be used to target us as voters and consumers, for good and ill, and often without our knowledge. These tactics will facilitate the spread of fake news and disinformation and make it easier for foreign interests to intervene in our elections—whether they are Russian trolls or British chancers.

Image credits: Tillis: US Senate; Cotton: US Senate; Robinson: US House of Representatives; Bolton: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia; Cruz: US Senate; Trump: White House; Mercer: Patrick McMullan/Getty; Wylie: Jack Taylor/Getty; Bannon: Jeff Malet/Newscom/ZUMA; Nix: Christian Charisius/DPA/ZUMA