Getty Images

A viral tweet spreading fake news about a non-existent terrorist attack on President Barack Obama once temporarily upset the stock market. When natural disasters strike, fake photos often flourish online. And the United States recently indicted 13 alleged members of a Russian trolling operation, in part for spreading propaganda on Twitter and Facebook during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Despite its ubiquitous presence, scientists say many questions remain unanswered about the growing reach of fake news.

That’s where a new report, published Thursday in the journal Science, comes in. The analysis, one of the largest ever done on the spread of false news online, included 126,000 stories spread by 3 million people more than 4.5 million times. And the findings are remarkable. Tweets about fake stories reached significantly more people, more quickly, than the truth, according to this new study. False news examined in the study was 70-percent more likely to be retweeted than the truth.

In the past, scientific research on how false news spreads has largely been limited to case studies following individuals events, or small samples. For this new study, three Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers—Soroush Vosoughi and Deb Roy of the Media Lab, and Sinan Aral of the Sloan School of Management—analyzed news stories distributed on Twitter from its start in 2006 to 2017.

They compiled a variety of storylines investigated by six independent fact-checking organizations (snopes.com, politifact.com, factcheck.org, truthorfiction.com, hoax-slayer.com, and urbanlegends. about.com) to create a database of “contested news”—that is, potentially viral stories that these organizations had scrutinized. Then, the researchers classified the stories as true or false; the fact-checking organizations agreed with each other on the stories’ veracity more than 95 percent of the time.

“Let’s say there is false news spreading around that Trump once said if he was ever going to run as president, he would run as a Republican because they are gullible,” explains Vosoughi, referencing a rumor about the president that has been entirely debunked. “We then looked for tweets spreading that rumor.” That included links to articles, people talking about the topic in their own tweets, and memes or other images.

Roy said he is used to seeing messy data results when doing research. But the difference between how false and true news spread was obvious.

“It kind of popped,” Roy said. “Like we were looking at two different species of something.”

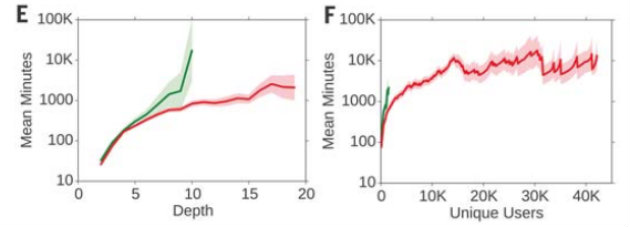

The number of minutes it takes for true (green) and false (red) rumor cascades to reach any (E) depth and (F) number of unique Twitter users.

Vosoughi et al.

The trio of researchers examined the likelihood that a tweet would create a “rumor cascade”—that is, a chain of retweets. They found that false stories often had significantly more “depth” on Twitter. In other words, a false tweets were more likely to hop, via retweets, from one user to another to another. All those retweets meant that false news stories were typically seen by more people than true stories were. While the truth rarely spread to more than 1,000 people, the most viral falsehoods routinely reached between 1,000 and 100,000 people.

The amount of false news on Twitter also continues to grow overall, and it tends to spike during important events, such as the US presidential elections in 2012 and 2016.

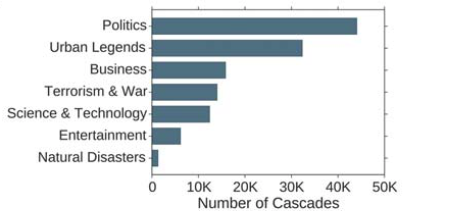

Of the types of false news the researchers studied, political news was by far the most virulent. It reached more than 20,000 people nearly three times faster than other types of false news reached half that many people.

The total number of rumor cascades (true and false news) across the seven most frequent categories.

Vosoughi et al.

False news was more “novel” than the truth, the study found, and Twitter users were more likely to share that novel information. An analysis of the language of tweeted replies also supported the role of novelty; false rumors inspired greater surprise, fear, and disgust, while the truth inspired greater sadness, anticipation, joy, and trust.

Users who spread false news had significantly fewer followers, followed fewer people, were less active on Twitter, were “verified” less often, and had been on Twitter for less time than users who spread accurate news. False news spread despite these differences, not because of them, the researchers said.

Interestingly, the researchers found that so-called bots accelerated the spread of both true and false news information at about the same rate. This suggests that “false news spreads more than the truth because humans, not robots, are more likely to spread it,” they wrote.

“I was somewhat surprised to see bots didn’t play a starring role,” Roy said.

Fil Menczer, an informatics and computer science professor at Indiana University who was not involved in the study, cautioned that we shouldn’t underestimate the ability of bots to amplify fake news. There are up to 60 million automated accounts on Facebook and up to 48 million on Twitter, Menczer reported in a recent study. In an article accompanying the Science study Thursday, Menczer joined 15 other prominent academics calling for greater research into the spread of misinformation online.

The study’s authors agree with that point.

“The old days of a gatekeeper making the decision of what is getting distributed are obviously over, or getting shifted,” Roy said. But much remains to be understood about the spread of fake news online. “It’s hard for me to put into a larger context how worried to be,” he added.