For all the clichés about sudden death and there being no tomorrow, sports were always supposed to be a substitute for reality, a place where Americans could fight for three hours and hug it out afterward. The newspapers used to call the sports pages the “toy department” for a reason. It was, after all, only a game.

But sports were always more than that for the black athlete. Sports was the place, at least idealistically, that fit the American Dream, where the scoreboard guaranteed fairness. Even that was an exaggeration, for when black athletes used their wealth and fame to exercise their full citizenship—as rich people do across the world—they were inevitably told to stick to sports.

A recent example came in February, when LeBron James appeared in a video discussing President Donald Trump on his multimedia site, Uninterrupted. James, long the best basketball player in the world and increasingly an unflinching critic of Trump, said the president’s frequent, harmful comments were “laughable” and “scary.” Shortly after the segment went online, the demagogic Fox News host Laura Ingraham told James to “shut up and dribble.” Her response, so harsh and absolute—reminiscent of Trump saying football owners should “get that son of a bitch off the field” for kneeling during the national anthem—was a reminder: In theory, sports were where athletes were seen as most American, but in reality, the minute a black player spoke about the American condition with even a hint of dissidence, the white public believed it could revoke his license to speak up.

Of all the black employees in the history of the United States, it was the ballplayers who were the most influential and most important, the ones who made the money. The black thinkers—the doctors, lawyers, scientists, and intellectuals—were roadblocked by segregation. Playing ball was the first occupation that allowed black Americans passage in the mainstream, permission to attend white universities and integrate white neighborhoods—a chance to be American without the asterisk. Black entertainers, for all their prominence, were never proof that America was fair, because John Coltrane didn’t have a scoreboard, a final buzzer that told you coldly and definitively who won. America liked that. Ballplayers were the Ones Who Made It.

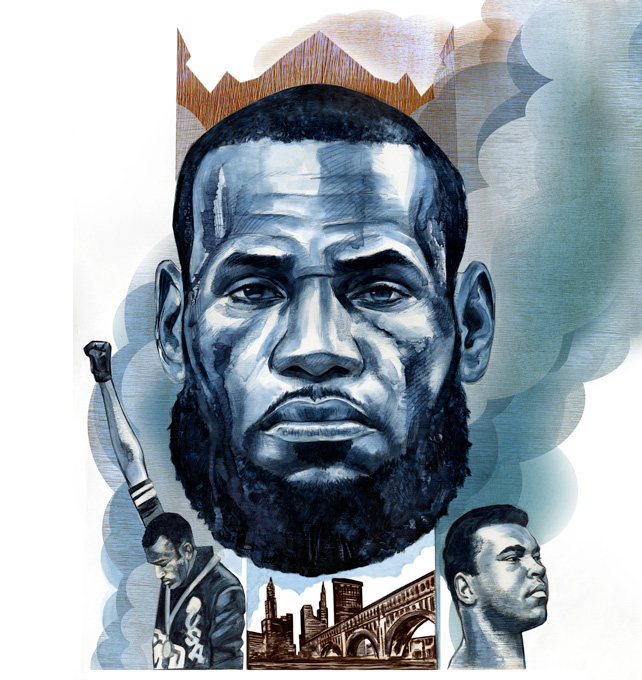

And being the Ones Who Made It soon came with the responsibility to speak for the people who had not made it, for whom the road was still blocked. The responsibility became a tradition so ingrained that it hung over every player. The tradition became the black athlete’s coat of arms, and the players who upheld it—Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith, John Carlos—would one day be taught in the schools. The ones who did not—the commercial superstars who followed, like O.J. Simpson, Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods—could never escape the criticism that they shrank from their larger duty to the people. The tradition was so strong that it even had an informal nickname: the Heritage.

LeBron James is the first black athlete since Ali to be both the best, most recognizable player in American professional sports and one who makes unequivocal support for black America inseparable from his public persona. Unlike Colin Kaepernick, who wasn’t a good enough player to protect himself from severe retribution by fans, media, and ultimately his league, James’ once-in-a-generation ability shields him, allows him to be himself. James does not hide from his liberal politics, publicly supporting Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. He loudly rejects Trump and his policies, and unlike Jordan, who kept himself at a corporate remove from social issues, James wrote a check and showed his face, unafraid of offending the white mainstream. He spoke up for Trayvon Martin after the teen’s killing in 2012, wore an “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirt following Eric Garner‘s killing by police in 2014, and has done what Jordan would not: give cover to the athletes without his talent and bank account to be more vocal politically. His leadership sent the message: Being a politically active black athlete should no longer be considered radical, but commonplace. Before his disgrace, Simpson was America’s first commercially viable black athlete, creating pathways perfected by Jordan and Woods, who enjoyed so much access to the good life that the sacrifices of Ali and the old guard seemed quaint and unnecessary. The Heritage is now back, with a difference: The player with the biggest number of zeros on his paycheck has grown to realize that being insulated from the fight by his money is no longer a compliment—or a victory.

But even James didn’t venture easily into the hard space of activism. He was shaped by the times when being an advocate for African Americans meant sometimes wandering into the unwelcome space that once belonged to the Heritage but was purchased at auction by Shut Up and Play. For when Tamir Rice was killed, James did not show up in Cleveland and walk arm in arm with the people, as Carmelo Anthony had done in Baltimore after police killed Freddie Gray. It would have polarized the city and altered the energy of his return to the hometown Cavaliers after his years with the Miami Heat. Like the rest of the modern incarnation of the Heritage, James was stuck facilitating “conversation,” being the bridge, ironically, to nowhere.

Then, in July 2016, James and his fellow NBA superstars Anthony, Chris Paul, and Dwyane Wade took the stage in Los Angeles at the ESPYs, ESPN’s annual glitterati and glamourfest award show, and officially announced joining the Heritage. Days before the show, James’ representatives contacted ESPN on behalf of the foursome with a request: They wanted to use the ESPYs to make a statement to America after a week of violence between black communities and police so gruesome that even Michael Jordan, now part of the ruling class as owner of the Charlotte Hornets, eventually released a statement.

In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 37-year-old Alton Sterling was killed by police after they confronted him for selling compact discs on a sidewalk. Then, in a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota, another black man, 32-year-old public school cafeteria worker Philando Castile, was shot seven times and killed by a police officer after being stopped for a broken taillight. The next night, Army veteran Micah Johnson ambushed and killed five police officers in Dallas in alleged retaliation.

Anthony, Paul, Wade, and James stood together on the ESPN stage, each dressed in a black suit. James went last: “It’s not about being a role model. It’s not about our responsibility to the tradition of activism. I know tonight we’re honoring Muhammad Ali, the GOAT [Greatest of All Time], but to do his legacy any justice, let’s use this moment as a call to action for all professional athletes.”

The negotiations between ESPN and the players had been intense. The network had tweaked and edited comments from the players that sounded anti-police, while the players worked with their teams and sponsors to ensure they were not harming their business partners. The editing of the statements continued right up until the show began. The message was powerful, but it was the result of compromise, concession. If the original goal of the Heritage, as Tommie Smith described it, was to support oppressed people around the world, the black athlete today resembled a privileged, corporate bridge between the races whose job wasn’t to advocate for black people—but to advocate for everybody. It was to be a peacemaker.

That meant being caught in the middle during a time when there is no middle. “The racial profiling has to stop. The shoot-to-kill mentality has to stop. Not seeing the value of black and brown bodies has to stop,” Wade said. Then, he added a negotiated, balancing qualifier, necessary to appease the corporate entities involved. “But also the retaliation has to stop. The endless gun violence in places like Chicago, Dallas—not to mention Orlando—it has to stop. Enough. Enough is enough. Now, as athletes, it’s on us to challenge each other to do even more than what we already do in our own communities. And the conversation cannot stop as our schedules get busy again.” Wade’s words underscored the corporate minefield today’s players tread.

Wade’s inclusion of the “endless gun violence in places like Chicago” was personal—it is his hometown—but was also seen as a negotiated appeasement to the “What about black-on-black crime?” sect. It was always a bizarre and illogical leap, a derivative of “shut up and play”: Black people kill one another, so why should anyone complain when the good guys kill them too?

Still, what James and the others said the night of the ESPYs should have been a call to action for all athletes. But just as in the 1960s, few white players have accepted the challenge. The police unions reacted to player protests by threatening to withhold services to events where criticism was expected to be on display. Black players found themselves where they had always been whenever they sought white support: pleading to be seen as full Americans to a public that only saw flag over grievance, authority over justice. It was about the most important black employees in America reclaiming a voice and responsibility from an American public that didn’t think they had ever earned the right to speak at all. And it was why many whites hated Kaepernick so. He did not negotiate. He was not a peacemaker.

So when James confronted Trumpism two years later with public defiance, Ingraham responded with an old weapon: an attempt to deny his voice—”Must they run their mouths like that?”—and, indeed, his citizenship. James and others shot back with I will not shut up and dribble, and Ingraham ultimately outed herself as a fraud, inviting James to appear on her show in a weak attempt to spin her condescending, racist attack into chummy celebrity banter. She failed, naturally, but her attitudes succeeded in reminding players, despite their millions and after all these years, why the Heritage endures: Even when African Americans think they’ve made it, they haven’t.

This essay is adapted from Howard Bryant’s new book, The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, out May 8 (Beacon).