Inside the largest of three tents set up to provide temporary shelter to homeless residents of San Diego.Matt Tinoco/Mother Jones

As the summer of 2017 drew to a close, a hepatitis A outbreak forced San Diego officials to confront the reality that their efforts to address the region’s homelessness crisis were failing. Street encampments concentrated in the city’s downtown area had become like a petri dish for the virus, which is spread by contaminated feces. Twenty people died and hundreds were hospitalized, at a cost of at least $12.5 million.

To stop the outbreak and to prevent another, the San Diego city council, at the urging of Mayor Kevin Faulconer, got aggressive about public health conditions on the streets. Besides dispatching the sanitation department to scrub the sidewalks with bleach, the city council authorized spending $6.5 million to erect three semi-permanent tent shelters where homeless people could bed down in safe and sanitary conditions.

This article is part of the SF Homeless Project, a collaboration between nearly 70 media organizations to explore the state of homelessness in San Francisco and potential solutions.

Within months, giant tents sprung up in the shadow of a downtown skyline increasingly defined by shiny glass towers of condominiums. Such a move was unprecedented in a West Coast city, where the number of unsheltered homeless people grew by 23 percent over the past two years. Though Oakland, Santa Barbara, and Seattle have built “sanctioned” homeless camps that provide basic services like trash pickup, San Diego’s tents are a departure from those questionably effective strategies. San Francisco’s Navigation Centers use a similar approach, but are based in permanent buildings instead of tents, their capacity limited by the city’s byzantine planning process.

The largest of the tents provides shelter for 325 people and about 70 of their canine companions. “These people are safe, and they have access to healthcare,” says Bob McElroy, founder and CEO of the nonprofit Alpha Project, which runs the tent. “Neither of those things happen if someone is sleeping on the sidewalk.” Built on a 50- by 310- foot parking lot, the Alpha Project tent and its surrounding site include bathrooms, showers, laundry machines, storage for resident’s belongings, and office-trailers for mental health and substance abuse counselors.

Technically, the tents are “bridge housing.” They’re intended as a temporary stop for homeless residents while they secure permanent housing. Besides being clean and safe, they also make it easier for on-site service providers to develop more effective and consistent relationships with the residents. McElroy says 17 different public agencies and nonprofit organizations serve his site; a veterinarian comes by weekly. He estimates that about 80 to 90 percent of the tent’s residents are affected by some kind of mental illness.

Like many other cities, San Diego is trying to pursue a Housing First approach to ending homelessness, which focuses on getting people places to live without requiring them to first have a job, or get medical care, or be sober. But construction of new low-income homes is a slow and laborious process, particularly in California.

“We have very progressive, liberal cities where people who are like, ‘Everything’s got to be permanent housing,’ coming down here because they know they have to have a place for people to stay [in the interim],” McElroy says. “LA has been down here five times [because] people are killing themselves out on the street. Allowing people to be sick and be in that environment and be victimized every day—it’s just bullshit.” (Following the example of its southern neighbor, Los Angeles is planning to build 15 similar tent structures within the next year.)

With its team of about 60 staffers—many of whom were previously homeless—the Alpha Project site is focused on first, helping people get a reliable job and then find permanent housing. If someone isn’t ready for a “real job,” they’re given other, low-stakes paid work like keeping the site and its surrounding neighborhood clean. (One of tent’s residents, McElroy says, just landed a $26 hourly job as a bus driver.) The goal is to build routine, and give people the time and space to get their lives back together after the extreme stress of living outside.

Matthew Doherty, the executive director of the US Interagency Council on Homelessness says bridge housing creates consistency for residents and those who serve them. “Rather than trying to work with people when they’re still unsheltered, which can cause a lot of difficulty following up with next steps, bridge housing gives them a safe and secure place to be,” Doherty says. “It’s easier to get them that help if they’re in a predictable place with staff assigned to work with them.”

The tent operated the Alpha Project houses 325 people and about 70 dogs.

Matt Tinoco / Mother Jones

Yet even under the best conditions, the path from bridge housing to permanent housing is a steep climb, largely because there are simply too few affordable places to live. James, who wouldn’t give his last name, who’s lived in the Alpha Project tent for six months, says that while he’s grateful for the facility’s resources and temporary stability, he doesn’t know where he’ll ultimately end up. “I’ll be 60 years old in September, and I have an income now,” he says. Since coming to the tent, he’s managed to break a cycle of drug and alcohol abuse that he’d fallen into after a messy divorce. “But I’m still working out getting placed somewhere to move out,” he says. “Even with the income that I’m getting, I cannot afford the rent in San Diego.”

The tents cost about $36 per person per day to operate. San Diego recently budgeted another $2.5 million to keep them open. When it approved the tents in 2017, the city council did so with the expectation that 65 percent of their population would move into permanent housing within about 120 days. Yet only about 12 percent of tent residents have been rehoused, according to the San Diego Union Tribune, prompting some to question whether the tents are a good use of money that would otherwise be spent on building permanent housing.

McElroy bristles at complaints that it’s taking too long to house people, saying 120 days was an arbitrary and unrealistic goal floated by “paperhangers” whose only relationship to the homeless is “seeing them outside their car at the offramp.” Housing that many people that quickly was unrealistic because there simply isn’t enough affordable housing available in San Diego. “We’ve housed over 100 people already, and we’ve done that with an inventory that does not exist,” he says.

James agrees that success can’t be tied to tight deadlines. “People who have been living on the street for four or five years, you can’t change them in four or five months. It takes time. It’s a process that you have to go through,” he says. “The media would have you think they aren’t moving fast enough. But you can’t do things overnight. Unless you’re God, you can’t expect to really change somebody in just a few months.”

Still, bridge housing boosters say temporary shelter is more cost effective than paying for people’s trips to the ER and, as McElroy says, “having the cops run after them.” As we walk inside the expansive rigid tent lined with hundreds of bunks, McElroy gestures to a beat-up fridge that he says saves millions of dollars of public funds. “Why does a refrigerator save the taxpayers money? Because a third of our population has diabetes or some other malady that requires their medication be refrigerated. When they don’t have medication, they have seizures, they get gangrenous limbs—hands and feet get cut off,” he explains in a deep baritone. “The primary care physician for people who live on the street is the emergency room. When they have a seizure because they can’t take their insulin—you see where I’m going with this? It’s common sense stuff that people don’t ever talk about. You don’t see homeless people walking around with a long extension cord and a refrigerator strapped to their back. So they get sick, and the taxpayers pay for it. When they’re in here, all of that goes away.”

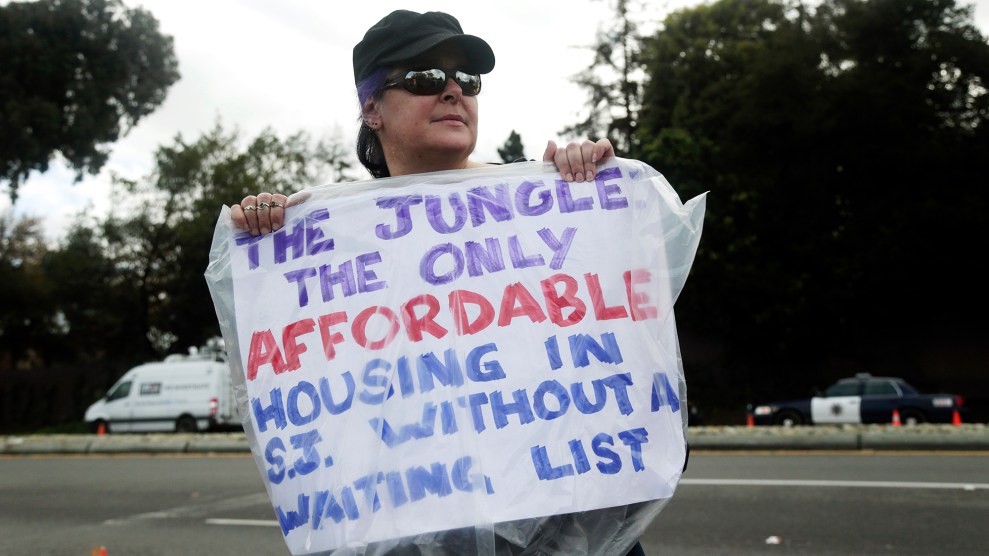

A deadly hepatitis outbreak spurred San Diego to set up sanitary housing sites.

Matt Tinoco / Mother Jones

At its core, the West Coast’s homelessness crisis is rooted in its housing crisis. In part due to decades of anti-growth politics, California cities don’t have enough housing for their growing populations. As more people compete for a place to live, the cost of housing has increased, squeezing those at the bottom of the economic ladder the most. A 2016 analysis by McKinsey determined that if California wanted to “satisfy pent-up demand and meet the needs of a growing population,” it would need to build approximately 3.5 million new homes by 2025. That’s about the same number of housing units as in all of Los Angeles County.

Short-term housing like San Diego’s structures is just one piece of the puzzle. On one hand, it’s important to make sure people aren’t dying in the street. On the other hand, bridge and other types of temporary housing are not long-term solutions to the housing shortage. “Our goal is not to pack as many people into short-term housing as possible, and get them to be out of sight and out of mind.,” says says Tommy Newman, the director of public affairs for the United Way Los Angeles, which is trying to address the root causes of homeless and poverty. “That’s not the solution. That’s not breaking the cycle of homelessness. We need to be talking about the lack of places to go.”

“When you start talking about land-use policies and zoning, people’s eyes sort of glaze over,” he continues. “But when you connect the dots between the RVs people see in front of their homes and the lack of affordable places for people to live, you can see the lightbulbs going on in their heads.”

Like James, a Alpha Project resident named Miche’le doesn’t know where she’ll go next, and wonders if she’ll end up back on the street. She says she’s five months pregnant and that she’ll have to leave the tent after she has her baby because it’s not set up to house children. “Granted, yeah, I’d rather be in a closed environment,” she says. “But it’s impossible for that to happen because of money.”

Miche’le says she struggles with mental illness, and that maintaining steady work has been difficult. She says she feels let down by the public agencies charged with helping people like her. “The housing projects are not helping, so instead they’re putting us in situations and places like this,” she says, gesturing at the site. “But supposedly this is only going to last two years. Well, where do we go after that? They’re making us go in circles. As exhausted as I am, I’m still trying to do what I have to do to get out of here. It’s irritating the tar out of me because I’m not getting anywhere.”