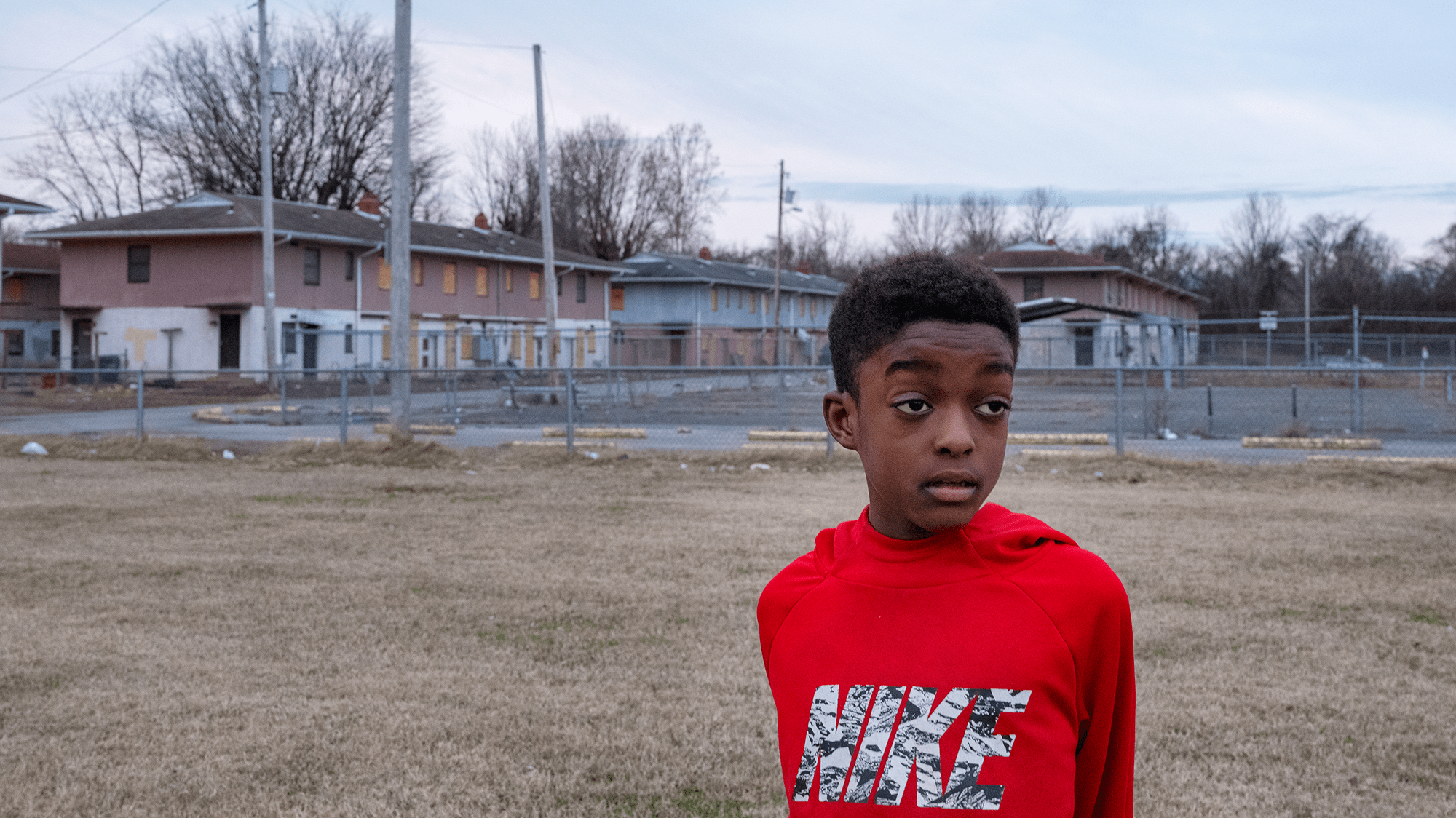

In April 2017, Demarion Duncan learned he’d have to move. That in itself would not be the end of the world; the McBride public housing project in Cairo, Illinois, where the 12-year-old Duncan lived with his mom, dad, and two younger siblings, was falling apart. A complex of 19 stucco-and-brick two-story apartment buildings abutting the Mississippi River levee on the backside of town, McBride was home to 103 families, including many of Duncan’s classmates, friends, and basketball teammates. But while a few units at McBride were still well maintained, others had mold in the bathrooms and flaking lead paint on the staircases. Heat worked sporadically; during cold snaps, Duncan, like many of his neighbors, bundled up and turned on the oven for warmth. Empty units and entire buildings were infested with roaches and rats.

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development had been debating what to do with public housing in Cairo for seven years and two presidential administrations, since federal inspections first uncovered grift, decay, and racial discrimination at the Alexander County Housing Authority. The mostly black residents of McBride and Elmwood, a sister project nearly two dozen blocks north that housed about 80 families, lived in squalor, while the white housing authority brass, under Executive Director James Wilson, blew public funds on boozy Vegas getaways and prioritized maintenance of the predominantly white high-rise across town. In the final year of the Obama administration, HUD placed the housing authority under receivership, but it left the future of Cairo’s public housing unresolved.

Ruddy Roye/VII

Cairo was the kind of troubled small town Donald Trump purported to champion—bypassed by the modern economy and starving for new investment. And no investment was as critical to its future as housing. Cairo’s fate would be one of the first major housing policy decisions of the Trump era, offering a glimpse of which priorities were real and which ones weren’t. So when HUD called a meeting in early April 2017, residents of Elmwood and McBride crowded into the pews at the nearby First Missionary Baptist Church, hoping for some good news.

Instead, HUD announced it was condemning the two projects. Residents would need to be out by July 2018, and HUD would give them vouchers for new apartments. The nicer high-rises across town, which had been favored with more attention and resources over the decades, would stay open, and a few residents would move into units there or find other arrangements nearby—but most of the African American families living in the segregated projects would have to leave Cairo. HUD claimed the city of 2,560 was “dying,” and that it would be pointless to replace or renovate 80-year-old buildings in a dying city. Such a sentence would be self-fulfilling—boarding up Cairo’s public housing would lead to an exodus of people, jobs, and funding.

Faced with the prospect of being scattered across the Midwest, Duncan and his classmates asked their sixth-grade teacher, Mary Beth Goff, whether there was anything they could do. With Ms. Goff’s help, they decided to write letters to the man who said their city was dying, the man with the power to make things right.

“Dear Ben Carson…”

Ruddy Roye/VII

Cairo—rhymes with “pharaoh”—anchors a part of southern Illinois known as Egypt, not far from the past or present hamlets of Dongola, Karnak, and Thebes. Egypt is hilly to the point of mountainous, but at its bottommost point it drops down to an alluvial plain until it is almost perfectly flat—not like a pancake, but like a waffle, with level fields of soybeans and corn bisected by a grid of levees. The city’s location on a teardrop of land where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi has bestowed on it an outsize place in American history and the annals of engineering. It is enclosed by seven miles of levees, 64 feet high, and can be entered from the rest of Illinois only by driving under an 80-ton floodgate.

Generations of civic leaders have stood at the confluence and envisioned a booming port, an intermodal hub, a new New York. Early land speculators swindled investors with a dazzling prospectus depicting domed buildings and steamboats, but they neglected to account for floods, leaving one of their rumored marks, Charles Dickens, to describe his investment as “a dismal swamp, on which the half built houses rot away” and “wretched wanderers…droop and die and lay their bones.” River traffic peaked in 1880, and the 10 railroads whittled down to one. The casino went to Metropolis. The nuclear plant went to Paducah, Kentucky. Cairo has lost nearly 90 percent of its population since its 1920s peak of more than 20,000. Aside from some barge work, a seed-oil processor, and a rice seed company, the housing authority, the county government, and the school system offer just about the only jobs in town. What is left is a once-lively place still filled with spirited characters, gossipy and a little claustrophobic, like the last hour of a party that is running long.

When Carson told a Senate subcommittee in June 2017 that Cairo was dying, he wasn’t saying anything residents hadn’t heard before, often with a thinly coded racial animus toward a city that is now 70 percent black. HUD’s decision to abandon the two largest housing projects there marked the culmination of colossal failures of local governance over half a century. In the 1960s and ’70s, Cairo’s lack of affordable housing for black residents fueled one of the longest and most violent conflicts of the civil rights movement. Until recently, Cairo had a higher percentage of residents living in public housing than any other city in Illinois, and some of those projects were nearly as racially segregated as they were 40 years ago. During the 1980s, Alexander County was the only place in Illinois subject to federal monitoring under the Voting Rights Act, because of its history of disenfranchising black voters. Cairo was uncommonly susceptible to the kind of bias and mismanagement that plagued the local housing authority, and because so much of its population lived in public housing, the town had an unusual amount to lose if anything went wrong. But Cairo’s crisis did not unfold in isolation. The housing authority’s past transgressions were known to HUD, and its raft of problems were in plain sight. HUD failed because HUD was set up to fail. And under Trump, the cracks Cairo fell through are getting wider.

HUD has become a front for an almost religious assault on the social safety net—under the first president ever accused of personally violating the Fair Housing Act (by refusing to rent to black tenants in the 1960s and ’70s). When he appointed Carson, a bureaucratic novice with no background in housing policy, Trump signaled his apathy toward a $50 billion agency. HUD quickly become a punchline, a magnet for hangers-on—Eric Trump’s wedding planner now oversees all public housing authorities in New York and New Jersey—whose blundering was encapsulated by the botched cover-up of Carson’s request to purchase a $31,000 dining-room set for his office. But the agency is also in the middle of a major reorientation. Carson may not know what he’s doing, but he knows what he wants. He once told an interviewer that poverty is “more of a choice than anything else”; by proposing to raise rents in subsidized buildings, slash budgets, and tear down homes, Carson and the Trump administration are forcing the working poor to choose something else.

But it’s not just about disinvestment. In the name of ending “social engineering,” Carson is rolling back the department’s efforts to enforce the kinds of fair housing rules that could have gone a long way toward fixing communities like Cairo. The city’s crisis was a product of the old HUD, an overmatched agency of sometimes conflicting motivations. Cairo’s tenuous future is a product of the new HUD, an agency so at odds with its own mission statement it is literally rewriting it.

Ruddy Roye/VII

Poverty isn’t a “state of mind,” as Carson put it last year, shortly after HUD announced its decision on Cairo. It is a consequence of things like disinvestment and discrimination. Nationally, more than 10,000 public housing units are lost each year to decay—about 100 McBrides—and the capital project backlog for existing buildings is growing by more than $3 billion a year. Many American cities, according to the American Sociological Association, are becoming more segregated, in part because of HUD’s lax enforcement of the Fair Housing Act. Meanwhile, Trump has proposed taking an ax to public housing funds and Carson has rolled back rules designed to combat segregation. His announcement in March, that he was considering editing the department’s mission statement by removing the Obama-era commitment to “inclusive and sustainable communities free from discrimination,” merely codified what fair housing advocates had seen for months. “What’s happening right now doesn’t just look like bureaucratic malaise,” says Betsy Julian, a former HUD official who runs the Inclusive Communities Project, a nonprofit focused on fair housing law. “It really does look like an intentional reversal of commitment to civil rights across the federal spectrum.” The whole point of HUD is that housing is foundational, that bad housing or a lack of housing or segregated housing spills over into everything else—schools, jobs, health. You don’t need to look any further than Cairo to see how.

After HUD announced in 2017 that it would close the McBride and Elmwood housing projects, residents began to pick up their vouchers, which had to be used within a year. HUD didn’t leave the tenants out to dry completely; it pledged to cover relocation costs and help residents find new homes. Buses would take them on weekly tours of nearby housing authorities—in Marion, Paducah, and Cape Girardeau, Missouri, each at least a 40-minute drive away. Paul Lambert would have none of it. “You can have 40 buses going anywhere you want to go, but I will not be on any one of them,” he said. “Nobody is gonna run me off.”

Lambert is 67 years old, tall and lanky with a graying goatee and a penchant for colorful tracksuits. He wears rings on eight fingers and speaks in a drawn-out cadence befitting a place that calls itself the Gateway to the South. Over the last four decades, Lambert has worked a succession of jobs. Now he takes care of his 23-year-old son, Sharonne, who has autism, while his wife, Bessie, works with special ed students at the public schools in Cairo. Lambert is a deacon at his church and a relentless advocate for every cause he’s embraced. He marched as a teenage activist in the civil rights era. In early 2017, his newest cause was his home.

Elmwood, which was open only to whites until the 1970s, had been Lambert’s home for almost his entire adult life, through several career changes and personal milestones. He married Bessie, raised three kids, and over 40 years filled a two-story, three-bedroom flat with the ambient accoutrements of life—furniture, books, and a framed portrait of his father, Hobert, on a Sunday afternoon stroll past the empty storefronts of Commercial Avenue. Lambert was close with his neighbors and distantly related to more of them than he could track. “My wife would always say she’s not moving until they put us out,” he said. “She said that years ago. It became true.”

Ruddy Roye/VII

The racial divisions were baked into the geography of Cairo when Lambert was growing up in the 1950s. Elmwood and McBride had opened during a boomlet of New Deal construction a decade earlier, using funds from President Franklin Roosevelt’s United States Housing Authority. One of the first federal ventures into housing, the agency shared a mission similar to the one HUD would later tackle, but with a catch: It maintained a federal requirement that public housing projects match the composition of their neighborhoods—ensuring segregated areas would stay that way. That suited Cairo’s planners just fine. Decades later, after the federal government had switched gears, officials would point to that directive as justification for their intransigence. Elmwood, open only to whites in the 1950s, was uptown, not far from the two mansions, Riverlore and Magnolia Manor, that evoked the city’s faded prime. Two dozen blocks to the south, McBride (then known as Pyramid Court) was reserved for blacks, including Lambert’s family.

The site of McBride had once been home to a Civil War “contraband camp,” where 5,000 ex-slaves had lived in humble quarters in the malarial dregs of town, and in the generations since, African Americans from the Mississippi Delta had hopped off train cars at their first stop on Northern soil and filled in the neighborhood. Whites lived where whites had always lived, blacks lived where blacks had always lived, and the burning crosses on the levee ensured they stayed there. “I didn’t see Elmwood until I was about 17 or 18 years old,” Lambert told me.

On matters of segregation, the county housing authority and the town were in lockstep. A few blocks south of Elmwood, David Lansden, the only white member of the Cairo NAACP, lived in a stately house on 29th Street, just off the millionaire’s row of mansions that flanked tree-lined Washington Avenue. In 1952, Lansden served as co-counsel in an effort to integrate Cairo public schools, working alongside Thurgood Marshall. For this effort he received slashed tires, rocks in his windows, and oil slicked across his stoop.

The loudest rebuke came from Lansden’s neighbor, Connell Smith, who bought a flashing neon arrow—the kind you might see above a seedy bar or truck stop—and placed it on his garage roof, pointing to the house behind him. “So I can see where the dynamite is going off,” Smith told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Smith was a powerful figure, a constable who had won the leadership of the Laborers’ International Union Local 773 in a bar fight. He was also on the board of the Alexander County Housing Authority.

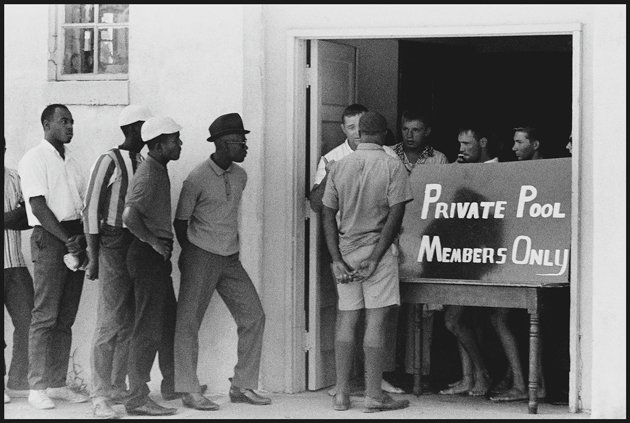

When Lansden won his case against the school district, the city dragged its feet. When Lambert was 12, John Lewis came to protest the whites-only swimming pool. The pool was sold and filled with cement. The Civil Rights Act passed, the Voting Rights Act passed, and Cairo stayed the same. In 1967, one of Lambert’s friends, a black 19-year-old Army private named Robert Hunt, was found dead in his cell at the Cairo city jail. The police claimed Hunt had been AWOL—he wasn’t—and that he had hanged himself with a T-shirt. But his body showed signs of a beating.

The city blew up. The five years that followed were a period of sustained racial violence unmatched in intensity and duration anywhere in the United States. Between 1967 and 1972, there were hundreds of shootings, dozens of arsons, and at least four deaths. Nazis marched in the streets. A team of doctors chartered planes to bring medical equipment for black residents, who were denied care at the city’s lone hospital. For three years, black citizens sustained a boycott of all white-owned businesses. It was, in the words of one news article read into the Congressional Record, a “domestic Vietnam, a symbol and symptom of national malaise.”

McBride became ground zero for the conflict. When the fighting was most heated, Lambert couldn’t enter or leave his apartment without a pass from the National Guard. In the late 1960s, a white vigilante group known as the White Hats formed in response to the unrest. The state forced them to disband, but their members, many of whom had been deputized by the county, continued to fire down on the projects from the levees. Residents shot back. Lambert joined a group called the United Front, which over the next half-decade would wage a protracted battle in the courts and in the streets. He worked his way up to chauffeur for its leader, Charles Koen, a charismatic young minister raised in McBride. Eventually, the cops gave Lambert a choice: join the military, go to jail, or leave town. He chose Milwaukee.

News cameras gravitated toward the violence, but the core of the struggle was a fight over civil rights, and housing played a central role. By the early ’70s, half the homes in Cairo were falling apart because of neglect. Many residents lacked plumbing. The city demolished some properties but built nothing in their place, and black residents, still barred from Elmwood and largely excluded from a newer public housing high-rise along the Ohio River floodwall—now known as the Connell Smith building—could turn only to McBride, where they lived under a constant threat of white snipers. The state of Illinois finally gave a grant to an interracial group of residents to start a nonprofit that could build new houses. Except the city refused to sell them any land.

Ruddy Roye/VII

The drama in Cairo played out at a formative moment in the history of HUD. The Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, just three years after the department had been created, was the last and perhaps most contentious of the landmark civil rights laws. The legislation didn’t just prohibit discrimination; it instructed the federal government to “affirmatively further” integration in public housing. But the law didn’t offer a lot of guidance on how to do that. Richard Nixon’s first HUD secretary, George Romney—Mitt’s father—gave it a try: He developed a program called Open Communities, which would cut off all grants to cities and states that failed to actively address segregation. Rather than leaving the responsibility of fighting segregation to a handful of staffers in a separate division—as would later become the case—Romney would use the full powers of the agency to coerce local authorities into following the law.

Fair housing may have enjoyed broad public support in 1968, but after a summer of riots and the election of Nixon, white liberals had grown timid and conservatives were ascendant. The backlash from reactionaries—none more important than Romney’s boss in the Oval Office—cost Romney his job in 1972 and put an end to Open Communities. For the next 40 years, with few exceptions, the carrot and the stick at HUD would be separated; HUD’s role as a piggy bank for local governments would often trump its responsibility to combat segregation. The first housing fight in Cairo was a textbook case for why HUD existed, but also an early indication of its limits. Absent a commitment from on high, HUD depended on local governments to work in good faith. And Alexander County’s all-white government had no interest in doing so.

After lawsuits from civil rights groups and a consent decree with HUD, the local housing authority finally agreed to hire one black leasing agent and give black employees the opportunity to work as managers. The housing authority was ordered to make desegregation a priority—black families would be moved into Elmwood, and white families would be moved into McBride.

Civil rights advocates wanted to make the consent decree indefinite and put a HUD staffer on the ground. Instead, federal monitoring ended after two years. “Given the history down there, to think that an order like that will solve the problems and end things was naive,” Michael Seng, who represented black plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the housing authority, told me. But the political appetite for proactively enforcing the Fair Housing Act had waned. In 1976, HUD washed its hands of Cairo.

While Lambert was ushering United Front leaders around the city and scrapping in the streets, James Wilson was growing up in a much different Cairo. Wilson, the son of a postal worker, lived down the street from the flashing arrow that linked the homes of David Lansden and Connell Smith. “I never marched in a parade or anything, but I was at rallies,” Wilson told National Public Radio in 1994, when asked if he’d been involved with the White Hats. He’d been too young to join, he explained, but “had I been 18 at the time, oh, I’m sure I’d have been a member. Everybody else was.”

Wilson was a different kind of good ol’ boy, a union guy and an emerging Democratic power broker in the area. In what amounted to a heresy in certain circles, he blamed the city’s white leadership—and not the United Front—for Cairo’s economic hardships when he first ran for mayor.

His election in 1991, two years after taking over as executive director at the Alexander County Housing Authority, seemed to represent a break with Cairo’s segregationist past. Wilson had beaten longtime Mayor Allen Moss—a White Hat—with backing from black pastors, unions, and many residents of public housing. Even now, Wilson’s legacy is the subject of debate. “I’ve always felt that James didn’t really have a racist bone in his body, and that’s unique for down here,” said Koen, the United Front leader. But Wilson didn’t fully break with the status quo either.

Ruddy Roye/VII

During his tenure, black residents started getting city jobs, and after a white police officer shot and killed a black man, Wilson appointed the city’s first black police chief. But the city didn’t “amalgamate,” to use Koen’s phrasing. As detailed later in a letter to HUD, black and white employees at the housing agency—where Wilson continued working as executive director throughout his time as mayor and for another 10 years after resigning from City Hall—had separate break rooms and separate responsibilities. White maintenance staffers only worked at the mostly white headquarters building, named after the man with the neon arrow, Connell Smith. Black maintenance staffers only worked at mostly black apartment complexes. Black workers were paid less for harder work and had no opportunity for advancement. “He maintained a relationship with the black community,” Koen says, “but it was a Southern relationship.”

Wilson talked about bringing Cairo out of the darkness of its past, of reopening the swimming pool and making a play for a riverboat casino. And outsiders continued to reflect their own dreams back on Cairo. In 2004, after winning the Democratic primary for US Senate, Barack Obama visited Cairo. In his memoir, and in countless stump speeches in the years to come, the future president described his anxiety as he approached the rally, and the relief he felt when the mostly white crowd opened up to him. “[I] believe,” Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope, “that moments like the one in Cairo ripple from their immediate point: that people of all races carry these moments into their homes and places of worship; that such moments shade a conversation with their children or their coworkers and can wear down, in slow, steady waves, the hatred and suspicion that isolation breeds.” Obama’s host that day was the son of Connell Smith. Cairo seemed to have hope too.

RELATED: Ben Carson’s War on HUD

But Wilson wasn’t a reformer; he was a political creature. Serving as mayor and housing agency director simultaneously gave him inordinate power, and he was in a position to grant jobs and favors to longtime friends. And the agency was a small fiefdom far removed from Washington watchdogs. The nation’s roughly 4,000 public housing authorities include a few enormous organizations that serve a third of all public housing residents, and a ton of small housing authorities with 500 units or less. Although they are authorized by federal law and must do Washington’s bidding to some degree, these agencies are part of local government, not HUD. Their executive directors are appointed by a public housing authority board, which is appointed by a county or city government. The Cairo agency’s $5 million in 2009 revenue came from a mix of federal funds, grants, and rent.

As agency director and mayor, Wilson looked out for his union above all else, bragging that the city’s benefits were the most generous in the state. And the union looked out for him—in his final mayoral campaign, Wilson received $52,000 from political committees associated with a government workers’ union, an extraordinary sum for a part-time job in a small town.

Ruddy Roye/VII

Wilson’s many hats might seem like an obvious conflict of interest. But with the nearest HUD regional office six hours away, he operated with a lot of autonomy. HUD relies on local governments to find people who can do the day-to-day administrative work. From its perspective, a well-connected mayor was probably the best it would get. In 2000, a year after a local minister sent a letter to HUD’s Chicago office pointing out Wilson’s conflicts of interest, HUD simply informed Wilson that he would need a waiver to continue holding both jobs—and promptly granted one.

Such stories bolstered Wilson’s reputation as a guy who knew the right people. By 2004, he’d beaten a felony charge for vote buying and an FBI investigation into the housing authority’s anti-drug task force. Cairo’s current mayor, Tyrone Coleman, then vice president of the local NAACP, attempted to gather signatures from residents for a formal complaint about the conditions at the housing projects, to no avail. “I think the maximum I ever got was like eight names.”

Among the first wave of black tenants to move into Elmwood after the consent decree ended in 1976 was Paul Lambert. His arrival seemed to flip a switch; within a matter of years, he told me, almost all of Elmwood’s white residents had left the public housing system and, in many cases, the city altogether. For a long time, everything still seemed in order. But Lambert was living in a ticking time bomb.

Elmwood and McBride are artifacts of an age when the federal government believed not just in subsidizing housing for low-income families, but in building that housing itself. Over the ’60s and ’70s, public opinion soured on that era of mass-produced housing. The altruism (and Depression-era pragmatism) that led to the first wave of public housing during the New Deal, and to the fair housing push of the Great Society, was crushed by the rise of white reactionary politics. In the age of Nixon and Reagan, conservatives made “public housing” synonymous with riots and drugs, and new construction was put on hold. Reformers, meanwhile, came to view such projects as misguided; they believed public housing should be dispersed, not concentrated. Prodded by HUD, local governments began to prefer voucher systems, shifting the burden of construction and maintenance onto private developers. But the demand far outstripped the supply. Nationally, 2.8 million households that qualify for public housing are on waiting lists for vouchers. That number would be three times higher if many programs had not simply stopped accepting applications. In 1998, Congress amended the Housing Act of 1937 to block HUD from expanding its housing stock. The result is that today, most public housing complexes in America are old. They are America’s Cuban cars, progressively more difficult and expensive to maintain as they age. New York City’s housing authority alone currently faces a $17 billion backlog in capital improvements. Meanwhile, between 1970 and 2000, public housing tenants got poorer and poorer without any increase in rental assistance funding. That means housing authorities need to fill an ever-widening budget gap with less and less revenue.

Ruddy Roye/VII

Ruddy Roye/VII

Wilson lost his mayoral race in 2003 but continued to serve as executive director for the housing agency. By 2010, the decay in Cairo was visceral. Maintenance stopped coming by and infestations went unchecked. “Like we were living in the Third World,” Lambert says. “Roaches running. You put a glue trap down and you check it in three days and it’s full.” Faced with a wave of gun violence that sometimes compelled kids to hide in bathtubs, Wilson installed tall chain-link fences and gates at Elmwood and McBride that locked at night so cars couldn’t enter or leave. The mostly white Connell Smith building got security guards.

Federal inspectors are supposed to notice these things. HUD’s Real Estate Assessment Center performs annual inspections on public housing units, but that work is contracted out and often faulty, only designed to pick up certain issues—mold, for instance, but not segregation. That’s the job of a different branch of HUD, the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, which is perpetually short-staffed and relies on complaints from residents or referrals from other offices for its leads. “Unless there is someone who can go in each and every one with a detailed civil rights checklist annually to look, and to do the evaluation and know what they’re doing, it is not possible to know the depth of the problems in all of these authorities,” says Sara Pratt, who was the deputy assistant secretary for enforcement and programs in the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity during the Obama administration. Her old office, she says, “is kind of the last to know.” And other branches of HUD are happy to keep it that way; an investigation gums up the works. It’s like calling the cops on your own party. One of the biggest items on fair housing advocates’ wish lists has been to make the fair housing office an entirely separate agency, like the Environmental Protection Agency.

Nonetheless, during the Obama administration, the wheels slowly started to turn. In 2010, HUD found that Cairo’s housing authority was improperly calculating its tenants’ rent in violation of federal regulations. HUD attributed this to simple incompetence and asked the agency to fix the problem. (In a lawsuit, tenants would later allege that they had been overcharged by hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars annually.) Two years later, a building inspection found “substandard” conditions at Elmwood and McBride. Wilson retired abruptly and promoted his former secretary, Martha Franklin, to replace him as executive director, but he continued as a paid consultant. In mid-September 2013, a group of HUD specialists drove down from Chicago for another meeting that would, finally, force the housing authority’s hand.

Wilson and Franklin met HUD’s team at the housing authority’s offices in the Connell Smith building, the tallest structure in Alexander County and the jewel of the housing authority. It was the only public housing complex in Cairo where the majority of residents were white. The Smith had security cameras and vending machines and a Christmas tree in the lobby during the winter. Lambert knew it well; he had been a security guard there for half a dozen years. Elmwood and McBride didn’t have security guards. Around the same time, Wilson had used capital funds to install a new headquarters for the housing authority on the third floor, giving the guests views of the barge traffic on the river below.

The meeting was a disaster. According to a later HUD memo, Wilson talked up his political connections, bragging that he could pick whomever he wanted to serve on the housing board, which is supposed to oversee the executive director. The inspectors noticed there were no African Americans in managerial jobs. According to the HUD report, Wilson “made several racist statements” indicating that black residents of Cairo were not capable of doing that work. According to another HUD document, Wilson also “stated to HUD staff that he was not going to force different races to live together.”

It was as if the consent decree had never happened. The only thing that had changed since the 1970s was that in addition to McBride—which had never desegregated—Elmwood was now 96 percent black. Most of the white residents who remained in the Cairo public housing system lived in the Smith building, which Wilson had made off-limits to families with children. (This was an unauthorized condition, which also mostly affected black tenants.) Wilson’s conduct was so abrasive that something unusual happened—the HUD officials complained to their own fair housing office.

The next two years would bring a frenzy of meetings and inspections as HUD tried to figure out what to do. Receivership might sound like the obvious solution. Why not bring on a team of professionals to right the ship? But HUD’s budget and staff were half what they had been in the early 1980s. Absent a real financial investment, an administrative takeover of the housing authority would only transfer the problem to someone else.

As HUD hesitated, the situation on the ground deteriorated in almost farcical ways. Franklin lasted less than two years. She was succeeded by an interim director who told HUD that “the desire of those in power” was to move minorities out of town, and who eventually stopped coming to work because he feared he might be “detained by county law enforcement” for crossing Wilson.

Ruddy Roye/VII

The dam began to break in the summer of 2015, after a reporter for the Southern Illinoisan, Molly Parker, obtained a copy of the HUD investigation. Residents of Elmwood and McBride, who had been kept in the dark as their grass went uncut, woke up one morning to learn that Wilson and Franklin had been double-charging the housing authority for travel expenses and putting hundreds of thousands of dollars of improper charges on the county card, including for booze and limousines. Lambert spearheaded a tenant group that drafted letters to state and federal lawmakers, and some residents organized a rent strike. Backed by a Chicago nonprofit, the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, which specializes in fair housing cases, Lambert and 29 other residents sued Wilson and the housing authority. Tenants began showing up at county commission and housing board meetings to air their complaints. One woman said she’d killed 17 mice in one month.

For a brief moment, there were even two rival directors—one backed by HUD, one backed by the local government—like some postrevolutionary junta. That, it seems, was the last straw. On February 19, 2016, the housing authority received a written notice that HUD was in charge effective immediately, owing to “an imminent threat to the life, health, and safety of the…public housing residents.”

When I visited Cairo this past December, HUD had just filed a $1.2 million civil complaint against Wilson and Franklin for making 198 false disbursement claims and falsely certifying that the local housing authority was compliant with civil rights laws. But Wilson isn’t acting like someone in legal danger. He keeps his 10 a.m. appointment for breakfast every morning at the town diner with a crew that includes a current city official.

After breakfast one day, he left a message for me saying he’d heard I was in town and recognized my out-of-state license plate at the diner. He seemed open to talking, but when I called back he balked. Wilson explained that he didn’t have a lawyer—an astounding claim for a man facing a seven-figure federal complaint—and didn’t want to risk incriminating himself. “I pushed the first black to be chairman of the housing board,” he said. “My record is beyond reproach.” Eventually, he hung up.

The letters from Ms. Goff’s class went out in April 2017. One student wanted Carson to know that the town was on the upswing. Another told Carson about going to McBride to visit her late grandma. The building reminded her of family, she said. If they tore down the projects, it would be like losing her grandma again.

Carson found himself on the defensive. The students made CNN. The president watches CNN. Carson wrote back promptly. In a warm but brief letter, he thanked the students for their messages. “You are living proof of the old saying, ‘Home is where the heart is,’” he wrote. In a separate letter to the superintendent, he got to the point. “I’ve had teams of experts searching for any viable solution to preserve affordable housing opportunities in Cairo, from rebuilding to utilizing manufactured housing,” he wrote. “Sadly there are very limited viable financial options for a nearly bankrupt housing authority.”

Up to that point, Carson had said very little about Cairo or anything else. The highlight of his first few months in office had been getting trapped in an elevator at a housing project in Miami. Nor did Carson seem to wield any special influence with Trump. In an email to staffers, Carson had downplayed the prospect of budget cuts shortly before the Trump administration proposed slashing the already beleaguered agency by 15 percent. Carson fell in line, stating that such cuts would prevent a culture of dependence. (Congress disagreed and increased HUD’s funding for 2018.)

But now Carson was arguing with sixth-graders. Carson explained that making McBride and Elmwood habitable would cost about $7.6 million. Replacing them outright would cost $70 million. The housing authority received $670,000 in capital funds from the federal government each year. The math was the math.

“The kids said, ‘We don’t even think he read our letters,’” Goff told me. “There’s no way he could have read what we wrote” and written what he did.

But public pressure did compel Carson to at least finally visit, and so in August he stopped by the high school gymnasium for a town hall meeting with residents. Lambert sat courtside in the first row of bleachers directly across from Carson, and he watched as Carson offered a rosy assessment entirely at odds with HUD’s own decision. “I think by the grace of God it’s possible to save this place,” Carson said.

One of the tragedies of Carson’s nomination was that Obama had offered the first signs of progress at HUD in years. Morale at the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity had improved, and while it was still short-staffed, the power balance between civil rights and funding had become a bit more even. The Supreme Court had ruled that housing discrimination could exist even when it wasn’t explicitly intentional—opening up new legal avenues for the executive branch to tackle segregation. And in 2015, after years of pressure from fair housing advocates, the Obama administration had finalized a new rule that would mandate local governments to report on their efforts to address segregation or risk being cut off from HUD funding.

Ruddy Roye/VII

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Carson had blasted that very rule, calling it a repeat of the busing era—“that brilliant social experiment” to usher in “racial utopia.” At his confirmation hearing last year, Carson doubled down. “I don’t have any problem whatsoever with affirmative action, or at least integration,” he explained. His problem was “people on high dictating it when they don’t know anything about what’s going on in the area.” Carson seemed to be actively unlearning the lessons of the last 50 years. In January, HUD suspended, until 2020, implementation of the order requiring communities to devise plans to proactively remedy segregation. In April, HUD proposed new work requirements and suggested raising the minimum rent for residents of public housing and recipients of Section 8 vouchers—in some cases tripling it. According to an analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, such a move would put nearly 1 million kids at risk of homelessness. (Carson eventually backed down.) Around that same time, the New York Times reported that HUD had put a freeze on some of the department’s investigations into fair housing complaints.

For as long as Cairo has been flailing, there have been would-be saviors. In the late ’80s, a professor of community development suggested that the way to change the city was by transforming it into a nice little reclaimed river town—Mark Twain’s Colonial Williamsburg. In the early 20th century, a prominent resident proposed turning the farmlands behind town on the Mississippi side into a giant maze that would deposit automobiles—should they make it that far—right in the middle of town. There’s been talk of a port authority for more than half a century.

Some of those plans had more flaws than others, but all suffered from one big problem—none of it mattered if the government couldn’t hold up its end of the bargain. There’s no alchemy to stable communities; they require working schools, jobs, and homes. It should not be surprising that students who sleep covered in Raid struggle in the classroom, or that residents paying more than half their money in rent aren’t starting businesses. Trump, throughout his campaign, had asked African Americans, “What do you have to lose?” Anyone in Cairo could have answered.

Since Carson’s announcement in April 2017, the town and the school have been shrinking. Most of Demarion Duncan’s friends have moved out of town, but he still sees many of his old buddies at basketball tournaments, and they meet up remotely to play Call of Duty and NBA Live on Xbox. Sometimes they’ll surprise him at church. In April this year, HUD held a second community meeting to inform the 40 families who remained that anyone not out by July 2 would be evicted, but by then, Duncan’s family had moved out too—they’d managed to find a house uptown. Duncan was still within walking distance of his grandmother’s place. “It’s not too big and it’s not too small,” he says of Cairo.

Because its state funding is tied to population and its tax base is shrinking, Duncan’s school has not been able to replace 13 of the 14 teachers who have left since April 2017—among them Mary Beth Goff. The city government is down to two workers to maintain its seven miles of levees. Of the 112 families who had left by February this year, the largest number stayed in Cairo or moved to the surrounding cities—Carbondale, Cape Girardeau, and Paducah. A group of families struck out together for Nashville, Tennessee. HUD said it wanted to accommodate residents who wanted to stay close to home by finding space at two other public housing properties up the road in Thebes—the Mary Alice Meadows and Sunset Terrace projects. The Thebes complexes, which at 30 years old are practically new by public housing standards, received little scrutiny from HUD during its Cairo investigation. The largest family buildings were integrated and residents weren’t complaining.

But then in February, after some families from Cairo had already relocated there, HUD announced it would shut down both those projects, too, citing the steep cost of rehabbing the buildings. That meant another 85 people—a quarter of the town of Thebes—would need to find new places to live. The process was starting all over again.

Alexander County was saving $500,000 in federal funds to repair a levee and would have nothing left to fix up apartment buildings. HUD has a capital fund to help communities cover the high cost of rehabbing crumbling public housing. But five days later, Carson would unveil a new HUD budget proposal that would wipe out this fund entirely. The idea, Carson explained, was to push people “toward self-sufficiency” by “moving aging public housing to more sustainable platforms”—except the sustainable platforms would get the ax too. If Carson’s vision for HUD were enacted, the budget cuts would move 200,000 families off Section 8 assistance, which helps tenants cover rent at privately owned buildings. HUD’s intervention in Cairo was at first presented as a stopgap measure until the agency could figure out a way forward. By the time the agency had to make a decision on Thebes, HUD had found its answer; slash and burn was the way forward.

Ruddy Roye/VII

The Lamberts were among the lucky ones. In December, I visited their new apartment in the Little Egypt Estates, a 10-unit building that was recently renovated and reopened to a handful of public housing exiles—the first new apartment complex to open in Cairo in decades. It had clean floors and Christmas trees by the front door. There were no children.

His new place was smaller, and even after he rented a storage unit up the road in Mounds, his living room was crowded with boxes and odds and ends. But everything worked, and it was affordable and warm.

Two days later, Bruce Rauner, Illinois’ Republican governor, dropped by for a quick photo op. Rauner, a private equity titan who in 2013 owned eight homes—many of them valued over $1 million—in six states, had been reclusive on Cairo, insisting it was a federal problem. But Cairo had become the kind of visceral issue that a politician running for reelection couldn’t avoid. There were Christmas cookies and soft drinks waiting for him at the Little Egypt Estates. Lambert was there too. “Can I get a picture with the governor?” Lambert shouted. He handed another attendee a disposable camera to snap the photo. “One, two,” someone started. “Governor!” Lambert said. Rauner and his entourage laughed.

“We need to help more entrepreneurs rehab some of the housing stock in the area,” Rauner said.

“Yeah, well, that’s what I’m thinking about—we need about 15 to 20 more of these guys,” Lambert said. “So they don’t have to relocate. Give them a choice.”

“That’s exactly right,” Rauner said.

“Give them a choice. If you don’t have a choice, you don’t have anywhere to go.”

“You just said the whole story right there,” Rauner said.

Rauner listened politely as he took a tour of a few apartments and accepted a blanket from Cairo’s mayor that was embroidered with icons from the town’s heyday. A few weeks later, the governor announced that his family charity would donate $100,000 toward redeveloping the port, the town’s white whale for nearly a century, and in June the state followed up with another $1 million for the project. The money for housing would have to come from somewhere else.