Julia Lurie, Mother Jones reporter:

When I first met Doc and Dre last August, they thought I was an undercover cop, or maybe a heroin user who was just getting started.

They were standing with a group of guys under an awning on a gray, humid afternoon on Baltimore’s North Avenue, smoking and chatting in the sticky heat. A steady stream of users came by, knowing to go straight to Doc, a 30-year-old who was quick to laugh and seemed to own this patch of cement. He’d reach into his jean pockets to exchange a baggie for a wad of cash.

I’d been in the Baltimore area with my colleague, filmmaker-in-residence Mark Helenowski, for nearly a week, reporting on a story that would turn into the documentary series Finding a Fix. I had been floored, as only a non-native would be, by how unconcealed the city’s drug trade was—how often we were offered pills, molly, or weed. Though we had packed our days shadowing drug users, cops, needle-exchange workers, and politicians on the front lines of the epidemic, we had yet to talk with full-time dealers.

I approached dozens of people that afternoon on busy corners and in parks, small notebook in hand. Most offered stories of addiction but didn’t want to speak on the record. Only Doc and his good friend Dre—calm and earnest compared with Doc’s bluster—agreed to talk, as long as we didn’t show their faces.

For the next couple of hours we huddled next to a McDonald’s in the rain as Doc and Dre told us about coming of age in a city ravaged by drugs. “Growing up, I didn’t even know what dope was, but I knew everybody that sold dope had money,” Doc said. He talked about the logistics of mixing fentanyl with heroin to hold onto customers, and about the Christmas presents and designer clothes he could buy for his kids as a result. After a stint in prison for drug charges, Dre, 38, was trying to find steady, legal work and had just applied for an overnight stocking gig at Giant grocery. Both men spoke of waking up overcome with painkiller cravings and realizing they were addicted to the same drugs they sold—drugs that, it turns out, kill all sorts of pain. “Some people done lost their best friend, their brothers over these fucking corner wars,” said Doc. “That’s their way of numbing.”

As a journalist, I often find that interviews blur together. But back at my desk in San Francisco, I kept thinking about Doc and Dre and their unusual candor. “If you’re just riding past, you say, ‘Look at that guy. Gold teeth, pants hanging off his ass,” Doc said at one point. “And then, you talk to me like, ‘Hey, that man’s a father. He goes to the schools.’ You say I’m a monster. I’m saying I’m surviving.”

A few weeks after the trip, I tried calling Doc but got a busy tone. It was Dre who broke the news: Doc had been shot in the early morning on September 19, just a block from where we had spoken. He died in the hospital. Dre had been urging Doc to take a step back—or at least deal from his phone, off the streets—but Doc wouldn’t listen. In the wake of the loss, Dre found himself using more, “dipping and dabbing,” he said. “I miss him every day.”

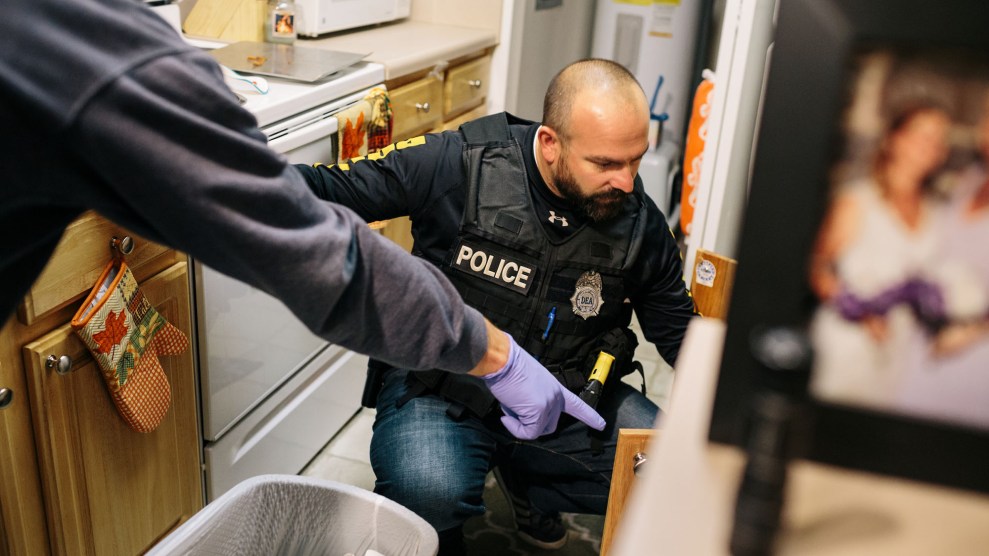

Dre stands at the corner where his friend, Doc, was shot and killed.

Lexey Swall

I hung up, made my way to our office lobby and into sun-filled downtown, walking circles around the block, confused about why I was crying. My approach to covering this epidemic fulltime has been to put up porous walls: be empathetic, but keep a distance in order to stay objective and find “the story.” Weeping over a guy I’d talked to for a couple of hours and worrying about his devastated friend didn’t fit that model. I didn’t know what “the story” was here or how it played into the broader narrative of unending overdoses across America. What I did know was that I wanted people not just to read about these men, but to hear their voices—to listen to the conversations that bookended the last days of Doc’s brief life, and to feel the quiet calamity of his death. I was thrilled when Al Kamalizad, our other filmmaker-in-residence, suggested making an animated video.

Dre and I check in once in a while. He still uses occasionally, but he has a steady income thanks to his new job at Giant, a loving girlfriend who gets mad at him if he takes too many pills, and an apartment where he lives with his mom just blocks from where we spoke. Sometimes, he listens to the audio from our first interview to hear his old friend’s voice. Every day, clad in a Giant uniform, he walks past Doc’s old corner on his way to work.

Al Kamalizad, Mother Jones filmmaker-in-residence:

As a filmmaker, I know it often takes hours of footage to craft something just a few minutes in length. But before coming to Mother Jones as a resident filmmaker, I never quite appreciated the amount of work—calling, texting, researching, database deep-diving, calling again and again—that goes into bringing investigative journalism to life. Behind each paragraph, there’s not just days, weeks, or months of research, but also some surprisingly close relationships. And when a journalist like Julia Lurie deals with a topic like opioid addiction, those relationships can be, at times, emotionally difficult to navigate.

As Julia and my fellow filmmaker-in-residence Mark Helenowski assembled the material for their three-part documentary series, Finding a Fix, last year, I came across a telephone interview Julia recorded with a source a few months after publication. Julia, sitting in her office in San Francisco, was on the line with Dre, a Baltimore man struggling with opioid addiction. I was bowled over. The conversation stayed with me because it demonstrated the strangely intimate yet distant relationship between a journalist and a subject. I thought it should be featured in a new and different way. So I made the animation above.

Watch the original documentary series, Finding a Fix, below: