A muscular white man in his mid-40s with a buzz cut and a tight black shirt is barking directions at the crowd: “When you hear the whistle, we’re going to line up against the yellow line on the ground. We’re practicing stance, draw, aim…Stance, draw, aim…” He demonstrates leveling his feet, pulling a pistol from his side holster, and pointing it forward with arms extended and elbows locked. His gun is aimed at a large rectangular target with a life-size photograph of a young white man in sunglasses menacingly pointing a gun.

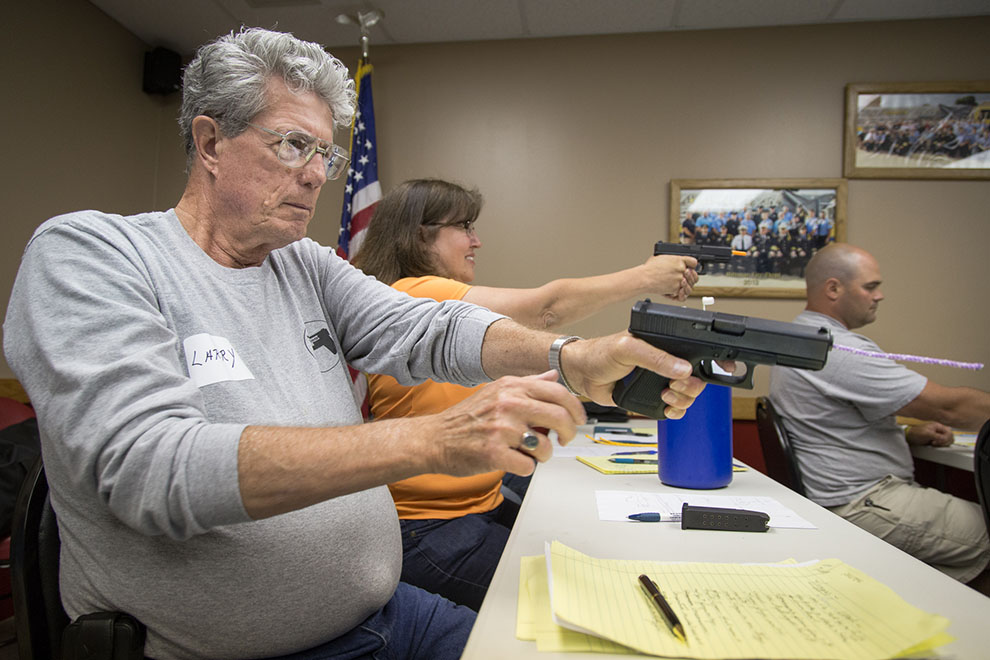

Today is the second day of a free, three-day class offered by the Buckeye Firearms Association, an Ohio-based gun rights organization. The attendees are mostly public school teachers and employees. There is a red-headed superintendent from a school district in northeastern Ohio, a couple in their late 20s who both teach physical education just outside Toledo, a slight woman who is a principal of a rural high school, and a pot-bellied custodian of a rural elementary school. Some have come from schools and districts that have already approved arming teachers and other campus staff, while others are there in hopes of going home to lobby for the practice in their communities. Many are here in secret and have been assured of the trainers’ discretion.

Since the massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, in December 2012, training programs like this one have been spreading throughout the country with little attention. I covered two of these trainings in the documentary I co-produced, G Is for Gun, which will air in September on the PBS WORLD Channel. The Trump administration’s push to arm schoolteachers has raised red flags for gun-control proponents, yet many Americans are unaware that there are already scores of teachers, administrators, school nurses, and bus drivers in at least 13 states packing heat. Shockingly, the exact number of states or schools with armed teachers is unknown.

Participants at a three-day FASTER (Faculty Administrator Safety Training and Administrator Response) gun training for school employees in Ohio

A school principal at the FASTER gun training for school employees

A central Ohio elementary school teacher practices her stance on the first day of the FASTER training

The Morton Salt factory on the outskirts of Rittman, Ohio, where a three-day gun training for teachers was held

According to my research, K-12 schools in at least 13 states have publicly disclosed the use of armed faculty and staff. Yet in some states, such as Ohio, school safety plans can be made in closed-door executive sessions, meaning that schools may make the decision to arm staff without necessarily notifying the public, and sometimes without notifying the police or state agencies. Over the course of our project we spoke to numerous school officials whose districts were arming teachers without telling the public. Sidney City Schools, the district we focused on in our documentary, did notify the public.

In 1990, Congress passed the Gun Free School Zones Act, which prohibited anyone from carrying or discharging a weapon within 1,000 feet of a school. The National Rifle Association, gun rights advocates, and Donald Trump have called for the act to be repealed, arguing that it serves as an invitation to would-be mass shooters. However, the law already includes an exception that allows people licensed to carry a firearm to bring their weapons into a school.

Much of the control over guns in schools rests at the state and local levels, where the laws are similarly thin. In eight states, a teacher or school staff member may be legally armed on school grounds so long as he or she has a concealed-carry permit. This was the case when a Utah elementary school teacher accidentally fired her gun in a school bathroom in 2014, shattering the toilet and embedding shrapnel in her leg. According to my own reporting and research by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, laws in more than 15 states contain explicit or possible exemptions to the prohibition of guns in schools. Gun carriers who have been given permission from school authorities or are part of school-sanctioned programs are commonly exempted.

A principal fires at a weapons training for school employees.

An attendee pretends to be a hostage.

Outside the Spot Diner in Sidney, Ohio, is a plaque commemorating a visit from George W. Bush in 2004.

The junior varsity football team practices in Sidney, Ohio.

A principal role-plays calling the police during a training.

Deputy Rick Cron looks out over students in the cafeteria at lunch time.

Ohio state legislators hear testimony regarding a bill that would expand guns in public spaces.

The laws don’t necessarily reflect what is happening on the ground. Schools in Massachusetts are unlikely to arm their teachers, yet the state code leaves that possibility open. Several rural schools in California began arming teachers last year; last October, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill that banned the practice. Many school boards in Rhode Island are supporting legislation that would eliminate their state’s exemption for armed school staff. Conversely, some schools in states such as Arkansas and Texas, where guns on school grounds are prohibited, have found loopholes in the law. A bill that would empower local school boards to vote on arming school staff is currently moving through the Pennsylvania Legislature.

So far, the majority of school districts that have said they are arming teachers have been in largely rural, mostly white communities. Yet schools serving low-income, black and brown students may feel the weight of misguided responses to school shootings. Since the Columbine shooting in 1999, concerns about school safety have often been met with an increase in police presence, metal detectors, and surveillance cameras, particularly in urban schools. The disproportionate effect of these security measures on students of color has been well documented. So far, the Trump administration’s approach to mass school shootings would continue this trend. Not long after the Parkland shooting, a Trump-appointed school safety commission announced the potential repeal of Obama-era guidelines for reducing race-based discrimination in school disciplinary practices. Last week, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos signaled her willingness to use money from federal grants that are earmarked for poor school districts to fund arming teachers.

A Sidney, Ohio, first-grade classroom

The historic Sidney Theater in downtown Sidney, Ohio