On a muggy August day in 2005, Desmond Meade stood in front of the railroad tracks north of downtown Miami and prepared to take his life. He’d been released from prison early after a 15-year sentence for gun possession was reduced to three years, but he was addicted to crack, without a job, and homeless. “The only thing going through my mind was how much pain I’d feel when I jumped in front of the oncoming train,” Meade said. “I was a broken man.”

But the train never came, and eventually Meade walked two blocks to a drug treatment center and checked himself in. He got clean, enrolled in school, and received a law degree from Florida International University in 2014. Meade should have been the archetypal recovery success story—“[God] took a crackhead and made a lawyer out of him,” as he put it. But he’s not allowed to practice law. And when his wife ran for the Florida House of Representatives in 2016, he couldn’t vote for her. “My story still doesn’t have a happy ending,” he said. “Because despite the fact that I’ve dedicated my life to being an asset to my community, I still can’t vote.”

Meade was recounting his experience this summer at a gathering of ex-offenders in Ocala, a conservative city of 60,000 in central Florida, 80 miles north of Orlando. Florida’s primaries were just days away, and there was an early voting center nearby, lined by signs for the candidates.

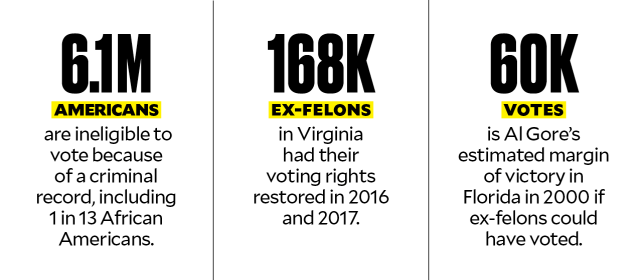

But 1.69 million Floridians like Meade aren’t able to participate in the 2018 elections. Florida bans people with felony records from voting, practicing law, or serving on a jury. Across the United States, 6.1 million felons and ex-felons can’t vote.* Some states prohibit people from voting while they’re on probation or parole or have unpaid fines, but Florida is one of only four, along with Iowa, Kentucky, and Virginia, that still bar ex-felons from voting indefinitely unless their rights are restored by the governor. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, Florida disenfranchises more citizens than Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee combined. Ten percent of the state’s adult population is ineligible to vote because of a criminal record, including 1 in 5 African Americans. Florida counts 533 different infractions as felonies, including crimes like disturbing a lobster trap and trespassing on a construction site. “Come on Vacation, Leave on Probation” is an unofficial slogan.

Meade, 51, speaks with the cadence of a preacher and has a physique befitting his former job as a bodyguard to the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Tupac Shakur. It was an oppressively hot day, and he and the 100 attendees—many of them older white men with tattoos who would not have looked out of place at a Donald Trump rally—took refuge beneath Spanish-moss-covered oak trees in a city park. He wore a black “Say YES to Second Chances” T-shirt. “This movement sits at the heart of a simple slogan: When a debt is paid, it’s paid,” Meade said. “We don’t care how you might vote or whether you vote at all, but every American citizen deserves that opportunity to at least earn the eligibility to vote again.”

Florida Rights Restoration Coalition President Desmond Meade speaks with state Sen. Dennis Baxley during the Florida Ex-Offender Reentry Coalition Reunion in Ocala, Florida.

Cassi Alexandra

In 2009, Meade became head of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC), and he was soon putting 50,000 miles a year on his car to help gather the nearly 800,000 signatures needed to place the Voting Restoration Amendment on the 2018 ballot. Amendment 4, as it’s called on the ballot, would automatically restore voting rights to as many as 1.4 million people with felony records who have completed their full sentences, but not those convicted of murder or a sexual offense. “It’s the largest enfranchisement of new voters since the Voting Rights Act,” says Samuel Sinyangwe, co-founder of StayWoke, an advocacy group started by Black Lives Matter activists. “It’s the biggest thing happening in the country with regard to voting rights.”

The amendment needs 60 percent of the vote to pass in November. That’s why Meade has been spending a lot of time in places like Ocala, in a county where 61 percent of voters backed Trump in 2016. In these hyperpartisan times, Meade’s group has assembled an impressively broad collection of allies that ranges from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Christian Coalition. Though it’s hard to predict support for ballot measures, one early poll showed Amendment 4 passing with 74 percent of the vote, including 61 percent support from Republicans. So far, there’s been no meaningful organized effort to oppose it.

Listen to author Ari Berman describe the push to give 1.4 million Floridians their vote back, on this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

This is remarkable, given that Florida voted for Trump and hasn’t elected a Democratic governor in nearly 20 years. Polls suggest voters there could oust three-term incumbent Sen. Bill Nelson in favor of Republican Gov. Rick Scott, the chief enforcer of the felon disenfranchisement law. But these same voters appear poised to back a measure that would undo a key part of Scott’s legacy and likely benefit Democrats in future elections.

As November approaches, there’s no telling whether the alliance to restore voting rights will actually hold, or whether the realities of zero-sum electoral politics will begin to fracture it. For now, it remains intact, and enough Republicans seem willing to support this huge expansion of voting rights even as the party has invested heavily in making it harder to vote nationwide. “We’re challenging the notion that only certain people care about voting rights,” says Faiz Shakir, the national political director of the ACLU, which has put more than $5 million behind Amendment 4. “Building a massive coalition across the ideological spectrum would send the most resounding message in a state like Florida. What you thought possible was totally wrong.”

Bernie DeCastro, CEO of the Florida Ex-Offender Reentry Coalition.

Cassi Alexandra

After the Civil War, the white Confederates who still controlled Florida had a problem: The state had been forced to accept the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which guaranteed equal rights for newly freed slaves, in order to rejoin the Union, and now black registered voters outnumbered white ones. White Floridians responded by adopting a constitution in 1868 that disenfranchised anyone with a felony conviction and added to the felony roster a variety of crimes they believed African Americans were likelier to be convicted of. One Republican leader said the law would keep the state from becoming “niggerized.” A decade later, more than 95 percent of people in Florida’s convict camps were African Americans.

In the same period, at least 12 other states—a third of the Union—adopted similar felon disenfranchisement laws. Before the advent of poll taxes and literacy tests, “felon voting restrictions were the first widespread set of legal disenfranchisement measures that would be imposed on African-Americans,” wrote Jeff Manza, Christopher Uggen, and Angela Behrens in the American Journal of Sociology.

The issue made national headlines in 2000, when Republican officials in Florida alleged that thousands of people with felony records were illegally registered to vote and needed to be removed from the rolls. African Americans made up only 11 percent of registered voters in the state but 44 percent of those on the purge list, which turned out to be riddled with errors. After the election, the state conceded that 12,000 eligible voters had been wrongly labeled as ex-felons and barred from voting. That was 22 times George W. Bush’s 537-vote margin of victory over Al Gore in Florida.

Manza and Uggen found that an estimated 70 percent of disenfranchised felons and ex-felons nationwide would have supported Democratic candidates from 1972 to 2000, so disenfranchisement laws had provided “a small but clear advantage to Republican candidates.” Laws blocking people with felony records from voting, their data suggests, may have handed at least six US Senate races to the GOP during that period. If ex-felons had been able to vote in Florida, Gore would have won the state by as many as 60,000 votes, according to Manza and Uggen. (Other studies have shown a smaller electoral impact from felon disenfranchisement laws because ex-felons vote at lower rates than the general population.)

In 2007, Republican Gov. Charlie Crist, a moderate who later became a Democrat, instituted a change that automatically restored voting rights to certain nonviolent ex-felons. But in 2011, Crist’s successor, Republican Rick Scott, reversed that policy and made the law even harsher. Now people with felony records had to wait five to seven years before they could petition the Clemency Board, helmed by Scott and three other Republican officials, to restore their rights. Under Scott, 90 percent of ex-felons have had their applications denied, and only 3,000 people have seen their rights restored, compared with 155,000 under Crist and 75,000 under his predecessor, Jeb Bush. Because of the long backlog, the wait time to get a hearing before the governor can stretch more than a decade. (In February, a federal judge called the system “crushingly restrictive” and said it needed to be reformed.)

Felon disenfranchisement has helped Scott and other Florida Republicans remain in power. Of the ex-felons granted clemency under Crist, 26 percent, or 40,000, registered to vote in the 2012 election, with 59 percent registering as Democrats, according to research by University of Pennsylvania professor Marc Meredith and Harvard doctoral candidate Michael Morse. In 2016, Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by 113,000 votes in Florida, but 500,000 African Americans were unable to vote. African Americans who did vote in Florida favored Clinton by a 76-point margin.

Meade applied to have his rights restored in 2006, but after Scott’s rule changes, “there was a slim-to-none chance,” he said. He joined FRRC, which had been founded by the ACLU of Florida and other groups after the 2000 election fiasco, and started driving around the state in his black Ford Taurus to build support for a ballot initiative to overturn the law. It was a quixotic crusade at first. “A lot of the experts didn’t think it was a smart thing to do or an appropriate time,” he said.

After 2016, groups like the ACLU put more money and manpower into initiatives protecting voting rights. But Meade also needed support from the Republicans whose party had benefited from the felon disenfranchisement scheme.

RELATED: How Jeb Bush Enlisted in Florida’s War on Black Voters

He turned to Neil Volz, a former Republican lobbyist, and together they became the odd couple of the felon voting rights restoration movement. Inspired by Newt Gingrich’s conservative revolution, Volz had gone to Washington after the 1994 election to work for Republican Rep. Bob Ney of Ohio. There he became friendly with superlobbyist Jack Abramoff. He accepted free drinks and sports tickets from Abramoff while doing favors for Abramoff’s clients, and soon he joined Abramoff’s firm to lobby his old boss. “I’m the poster child for the revolving door,” he said later. In 2006, the scheme unraveled in spectacular fashion. Volz pleaded guilty to conspiring to corrupt public officials and was sentenced to two years of probation, plus a fine and community service. He provided the government with evidence against Ney, who received 30 months in prison.

Volz said he was “radioactive” in Washington, so he moved to Fort Myers, Florida, where he knew no one. He couldn’t vote in the state and had trouble finding a job. “It was very eye-opening to see how many people wouldn’t hire me because I had a felony conviction,” Volz told me over eggs and hash browns at a Waffle House in Orlando. For a time, Volz worked as a night janitor at a restaurant. “I could see the White House from my office, and then you go to scrubbing toilets every night,” he said. “It was humbling.”

In 2015, Volz saw Meade speak at Florida Gulf Coast University. “I walked in, and my initial reaction was, ‘This isn’t my scene,’” Volz said. “‘This is a liberal thing going on in here.’” But Volz quickly realized it wasn’t just a liberal issue—a lot of white Republicans like himself couldn’t vote, either. (Only one-third of Floridians with felony records are black.) “The cancer started 150 years ago with Jim Crow, but now it’s grown and infected the entire body,” he said. “You can’t go into a community in Florida and find someone who’s not impacted by this policy.”

Florida Rights Restoration Coalition President Desmond Meade and Political Director Neil Volz.

Cassi Alexandra

Volz started volunteering with FRRC. During the 2016 campaign, he collected signatures at Trump rallies to get Amendment 4 on the ballot. “People with ‘deplorables’ T-shirts would put their arms around me and say, ‘Yeah, man, that’s my family,’” said Volz, who became the group’s political director after the election. “We got lots of signatures.” When it comes to support for Amendment 4, he said, “bloodlines are thicker than party lines.”

He had recently attended an Orlando gathering of politicians and advocates interested in criminal justice reform. The general counsel of Koch Industries was there, as were representatives from the Christian Coalition, the evangelical group founded by Pat Robertson, and the Prison Fellowship, started by former Richard Nixon special counsel Chuck Colson, who went to prison for obstruction of justice during the Watergate scandal. Volz pointed out that ex-felons who have their voting rights restored are less likely to commit future crimes, according to data from the Florida parole commission. He also cited a study commissioned by Amendment 4 supporters finding that the amendment would boost the state’s economy by $365 million annually, because people with felony records would be more likely to find jobs and less likely to go back to prison. (An analysis by the state of Florida couldn’t determine the fiscal impact of felon reenfranchisement.)

Conservative supporters of Amendment 4 want to reframe how people think about ex-felons. The advertising campaign for the amendment this fall features Republicans, veterans, and former opioid addicts. “We need to create a system that isn’t so interested in being tough on crime but is more interested in being effective,” says Keith den Hollander, the national field director for the Christian Coalition, which is encouraging its more than 150,000 members in Florida to back Amendment 4. “The more we marginalize and stigmatize people who have made mistakes, the more we take away their opportunities in life.”

Partly because of this conservative support, no major groups have emerged to oppose Amendment 4. The Republican Party of Florida has remained neutral. A spokeswoman for Gov. Scott told the Tampa Bay Times, “This is a decision for each voter to decide on.” Howard Simon, the executive director of the ACLU of Florida, says, “Everyone believes in second chances now. We already won the language war.”

At the event for ex-offenders in Ocala, I met Bill Eagan, the chaplain of a Tampa-area chapter of a motorcycle ministry called FAITH Riders. He wore a Harley-Davidson T-shirt and a black leather vest with an image of a cross over a bald eagle and an American flag. “Up until three years ago, I was pretty hard on a lot of ex-offenders,” said Eagan, who described himself as conservative. “I never knew anybody personally.” But now he was helping people with criminal records reintegrate into society. He drove up to Ocala with a 61-year-old black man named Sylvester Harris who had served 41 years in prison for murder and robbery. Eagan told me he was “on the fence” about Amendment 4, but he said, “I’ve softened on it. I was a definite no. Now I’m getting to know these guys personally and hear their stories.” He mentioned how Meade recounted that Jesus had offered forgiveness to the thief on the cross next to his. “I had never thought of his argument before,” Eagan said. “I’ve got some serious thinking to do.”

RELATED: Republicans Across the Country Have Restricted Ballot Access. Now Voters Are Fighting Back.

The evolving views of people like Eagan could ease politicians’ fears of being seen as soft on crime. Democrats have been scarred for decades by Willie Horton-style attack ads, while Republicans have competed to see who can lock more people up. That may be starting to change. In 2016, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe began restoring voting rights to 168,000 people with felony records. When Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, who supported the policy, ran to succeed McAuliffe, his Republican opponent, Ed Gillespie, aired a TV ad claiming that Northam had made it easier for “violent felons and sex offenders” to serve on juries and buy guns. Northam won by 9 points, and postelection surveys found that Gillespie’s ad had backfired, making black voters less enthusiastic about his candidacy. After the election, Gillespie said he regretted raising the issue and wished he could have focused on criminal justice reform.

In Florida, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Andrew Gillum, who’s hoping to become the state’s first black governor, has spoken openly about how his three older brothers ran afoul of the law while growing up in a working-class part of Miami. “I believe firmly that people deserve second chances,” he said in a campaign video. “You make mistakes, you break the law, you pay the penalty, but you ought to be given a second chance.”

The Amendment 4 campaign comes amid a broader push by Democrats to reverse some of the widespread voting restrictions Republicans have implemented since 2010. Fourteen states, including red ones like Alaska, have adopted automatic voter registration in recent years. In November, voters across the country will decide on a range of ballot initiatives to expand voting rights, including some that would make registration easier or draw legislative districts in a nonpartisan way. These measures are a key tool for voting rights advocates at a time when Republicans control a majority of statehouses and the federal government. “We’ve been playing on defense for ages on voter ID laws and all manner of voting restrictions,” says the ACLU’s Shakir. “One of the major storylines of 2018 will be: This is the year we went on offense and expanded voting participation.”

Amendment 4, in particular, could boost turnout among black voters and young voters, who tend to vote in smaller numbers in midterm elections but helped deliver the state to Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012. “This is the single most compelling thing that folks want to vote for in November,” says StayWoke’s Sinyangwe. His group went door to door in black communities in Orlando over the summer and found that voters were far more enthusiastic about supporting Amendment 4 than about voting for Democratic candidates for Senate or governor. (This was before Gillum’s primary victory, which could also increase black turnout.) But ominously, only half the residents StayWoke spoke with knew about the amendment. “This can play a huge role in boosting turnout, particularly in black communities, but that can only happen if folks are aware it’s on the ballot,” Sinyangwe says.

The biggest roadblock for the Amendment 4 campaign is that the constituency most harmed by the policy can’t vote to change it. Of the people StayWoke talked with who weren’t registered to vote, one-third couldn’t register because of a felony conviction.

When I met Meade’s wife, Sheena, and their 19-year-old son, Xandré, the pair had just come from voting in the primaries and wore “I voted” stickers. It was the first time Xandré had cast a ballot—something his father hasn’t been able to do since before Xandré was born. “It felt really good,” he said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated who is included in the 6.1 million figure.