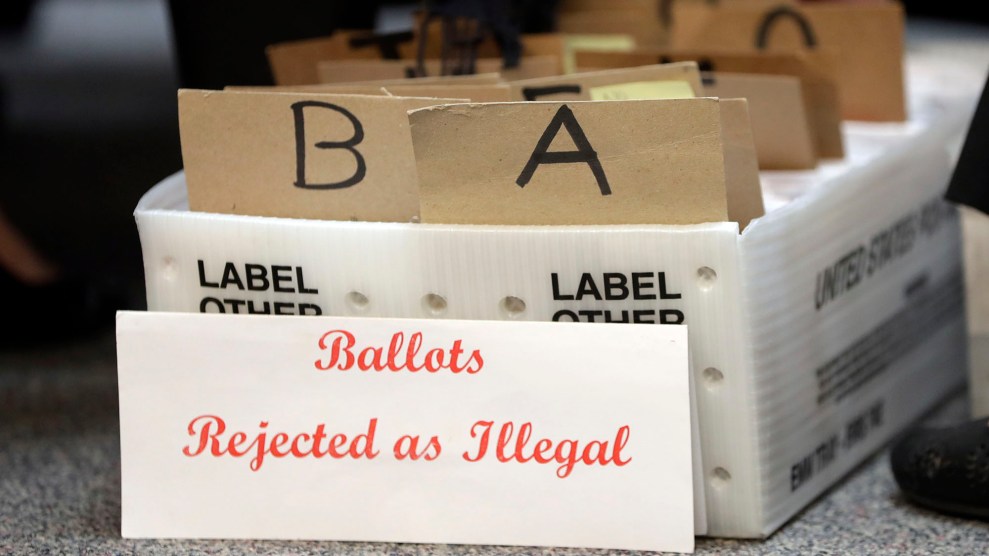

Rejected mail-in ballots sit in a box as members of the canvassing board verify signatures at the Miami-Dade County Elections Department on Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018, in Miami. Lynne Sladky/AP

Since moving to Florida in 2007, Paul Cauchi has voted in person in his Miami-Dade county precinct. But this year, after the county made a big push for vote-by-mail, he decided to give it a try. He labored over the lengthy ballot stuffed with amendments, then, as he recalls, carefully signed the envelope and sent it in.

But when he went on the county’s online voter information portal earlier this week to ensure that his ballot had been counted, he discovered an error message: his signature either didn’t match the version on record with the county, or he had failed to sign the envelope at all. “I felt really frustrated by it, and disappointed,” he told Mother Jones. “This is probably happening to other people.”

Florida is one of a handful of states with a signature-matching law. Such laws require that the signature on the envelope of an absentee ballot match the signature on file with county election officials. In a state with razor tight races for governor, US Senate, and many House of Representatives seats, absentee ballots rejected over signature issues could prove greater than the candidates’ margins of victory. Signature problems affect voters of all of all parties and demographics, but data shows young and minority voters, as well as registered Democrats more broadly, are more likely to have their ballots rejected. While Florida counties are required to notify and provide voters with signature problems a chance to correct them before Election Day, county procedures vary widely, and the same demographic groups are less likely to be given an opportunity to fix any error.

In Florida, each county’s three-member canvassing board decides whether a signature matches. “There’s no expert or standard,” says Daniel Smith, the head of the political science department at the University of Florida. “It’s in the eye of the beholder.”

As of Thursday morning, 15,765 absentee ballots had been rejected due to a signature issue, according to data reported by Florida counties and made available to Smith, who has long studied the issue. Of those, 12,261 have no signature and 3,504 have some other signature error, including mismatches.

Two percent of absentee ballots cast by voters ages 18-29 had problems, according to Smith’s latest 2018 data, compared to less than half a percent for voters 65 years and older. Votes sent in by African Americans accounted for just 8 percent of overall absentee ballots, but made up 17 percent of absentee ballots set aside with a signature issue. Overall, absentee ballots from registered Democrats were about about five percentage points more likely to have signature issues.

This year is not an outlier. Florida’s signature law had a disproportionate impact on young and minority voters in 2012 and 2016 as well. Earlier this year, Smith conducted an analysis of the issue in those election cycles for the Florida ACLU. In 2012, he found nearly 24,000 absentee ballots were rejected under the law. In 2016, the number rose to nearly 28,000. That year, voters under the age of 30 cast just 9.2 percent of absentee ballots, but accounted for 30.8 percent of all rejected mail ballots. Minority and younger voters were less likely to cure the problems with their ballot than older and white voters.

In recent years, federal courts have taken issue with signature matching laws around the country. Last month, a federal judge in Georgia blocked election officials from rejecting ballots with mismatched signatures without giving the voter an opportunity to fix the problem. The order came after Gwinnett County, just outside of Atlanta, posted absentee ballot rejection rates of just 2.5 percent for white voters, but nearly 15 percent for Asian Americans and 8 percent for African Americans. In August, a federal judge struck down a New Hampshire signature law; in March, a federal judge in California ruled the state must give voters a chance to correct signature errors before rejecting a ballot.

On the eve of the 2016 election, a federal court ordered Florida to give absentee voters judged to have provided a mismatched signature an opportunity to prove their identity and have their ballot counted. Federal Judge Mark Walker wrote that the state had “categorically disenfranchised thousands of voters arguably for no reason other than they have poor handwriting or their handwriting has changed over time.” In 2017, the legislature codified the requirement, giving affected voters until the day before the election to submit a signed affidavit and a copy of their ID in order to have their ballot counted. (No remedy is available for absentee ballots with signature issues that arrive on Election Day.) But the law offered no detail on how counties should notify voters with ballot signature problems, and the secretary of state has not issued any protocols. As a result, a voter’s odds of having their rejected ballot ultimately counted largely depend on what county they live in. In 2016, around 1 percent of mail-in ballots were rejected statewide, but in Miami-Dade, the state’s most populous and diverse county, the rate was nearly 2 percent.

When Smith was preparing his study for the ACLU, he asked supervisors in all 67 counties about the procedures they used to notify voters. The responses showed drastically varying levels of effort. In some smaller counties, election officials will attempt to find phone numbers or email addresses, or even visit homes or send Facebook messages. Other counties simply mail a notice, which may not be received before the deadline. Some counties told Smith that they viewed listing the ballot’s issue on a website as providing sufficient notification under the law. If an affected voter in those counties didn’t think or wasn’t able to check the status of their mail-in-ballot online, they would never know that it had been rejected.

This may be what happened to Cauchi, who only found out his ballot was hung up after consulting his county’s elections website. He says it’s possible he will receive a notice in the mail, but as of Thursday, he had not, and because he was traveling this week, he says a notice might not have helped clue him in in time to send an affidavit. Miami-Dade county election officials did not respond to Mother Jones requests about their notification policies.

Paul Lux, the election supervisor in Okaloosa County and president of the Florida State Association of Supervisors of Elections, described the extraordinary lengths his county goes to to notify people with rejected ballots. Earlier this week, a staffer drove to the home of a voter who had failed to sign his ballot with the affidavit as well as a machine to photocopy his ID. To Lux, putting the information on a website doesn’t seem sufficient to fulfill the state’s notification requirement. “I certainly do not feel that is what the law currently calls for,” he said. “Reaching out to them, making contact, is different than just posting on your website, in my opinion.” (A spokesperson in the Florida Secretary of State’s office did not have an answer to whether such a policy would satisfy the law.)

Ironically, absentee ballot racial disparities seemed to worsen after the notification requirement went into place in October 2016. Rather than lower overall rejection rates, Smith found young and minority voters were more likely to have their ballot rejected under the new regime. White voters, however, were even less likely to have their absentee ballot rejected. The reason isn’t entirely clear, but one possibility is that minority and younger voters are concentrated in larger counties without the resources to do aggressive outreach.

After finding out that something was wrong with his ballot, Cauchi submitted an affidavit and a copy of his drivers license to Miami-Dade election officials. On Friday, the notice that his ballot had a signature error had been removed from the website. He assumes that means his vote has been counted.

What’s unclear is how many other Floridians will not even realize there is a problem with their vote, only have their ballots thrown out.