Tom Williams/ZUMA

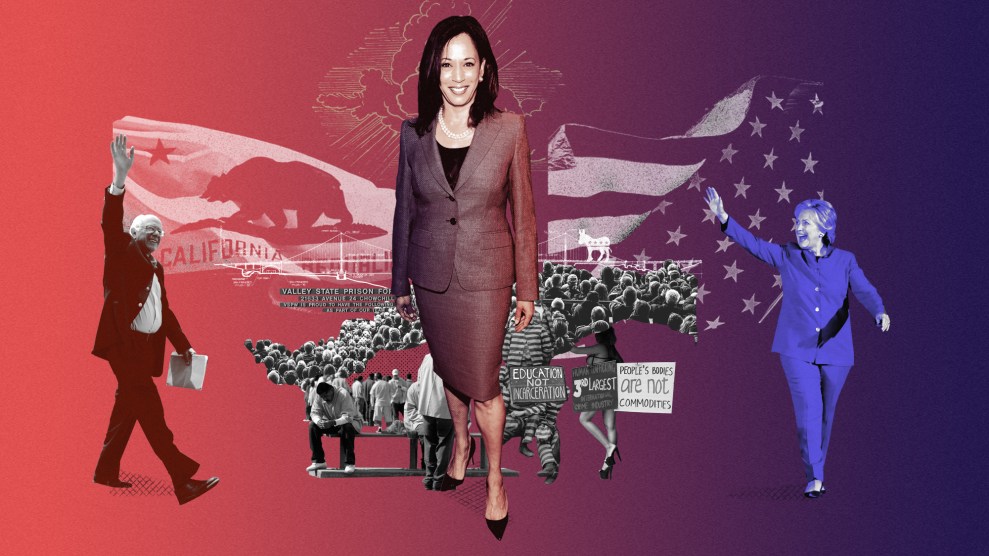

It’s finally official: Kamala Harris is running for president.

She made the announcement on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, meaning that the biracial junior senator from California is only the third black woman (after Shirley Chisholm and Carol Moseley-Braun) and second Indian American (after Bobby Jindal) to make a major party run for the presidency. “I love my country,” Harris said in an interview on ABC’s Good Morning America that coincided with the video. “This is a moment in time that I feel a sense of responsibility to stand up and fight for the best of who we are.”

Harris will hold a formal campaign rally in her hometown of Oakland on Sunday, January 27. Before that, she’ll make a campaign stop in South Carolina to headline a gathering of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the influential black sorority she joined while studying at Howard University in the early 1980s.

I'm running for president. Let's do this together. Join us: https://t.co/9KwgFlgZHA pic.twitter.com/otf2ez7t1p

— Kamala Harris (@KamalaHarris) January 21, 2019

The announcement caps off nearly two full years of speculation about Harris’ political future. She was elected to the Senate in 2016 after winning two terms as California’s attorney general and serving seven years as district attorney of San Francisco. Almost immediately after she was sworn into federal office in 2017, Harris was branded by pundits, observers, and supporters as a hero and foil to the newly elected President Donald Trump. That positioning had as much to do with her identity—a black woman raised by an Indian immigrant mother and Jamaican-born father who met while attending civil rights protests in Berkeley in the 1960s—as it did with the promise she made on election night to fight Trump’s policies.

During her time in the Senate, her public profile has grown tremendously, thanks in large part to several high-profile grillings of Trump administration officials and allies. Former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh have endured Harris’ televised cross-examinations, which earned her cheers from the left and outrage from the right. She’s also staked her flag on a host of progressive policy issues, including backing Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All, teaming up with Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) for a bail reform bill, and sponsoring a historic proposal that would make lynching a federal crime.

But the presidential run will certainly invite the most unfriendly fire of Harris’ career. And it won’t just come from conservatives. Harris has long considered herself to be a “progressive prosecutor,” a notion that has gained currency in recent years as figures like Chicago State Attorney Kim Foxx and Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner have promised to reform criminal justice from the inside. Harris’ argument that she was doing the same when she was prosecuting drug and sex abuse cases in Oakland 25 years ago hasn’t protected her from criticism that she was a key participant in a system that disproportionately incarcerates black and Latino men and women.

This criticism was especially pronounced during Harris’ tenure as California attorney general, when she supported laws punishing parents when their children are chronically truant. She was also hammered for prosecuting Backpage.com—some say to the detriment of sex workers—and slammed for being cautious on a host of other matters, including not prosecuting now-Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin for foreclosure violations stemming from his time as CEO of OneWest Bank.

In a small preview of what’s likely to come, on Thursday the New York Times published a damning op-ed from Laura Bazelon, the former director of the Loyola Law School Project for the Innocent in Los Angeles. “It is true that politicians must make concessions to get the support of key interest groups,” she argues. “The fierce, collective opposition of law enforcement and local district attorney associations can be hard to overcome at the ballot box. But in her career, Ms. Harris did not barter or trade to get the support of more conservative law-and-order types; she gave it all away.”

When I profiled Harris for Mother Jones in 2017, I saw up close the delicate way that she was working to straddle the line between an enforcer of existing laws and a crusader for more just ones. Perhaps more than any other chapter of her career, this balance is evident in her time as San Francisco district attorney, when she piloted an innovative program called Back on Track that offered alternatives to prison for first-time nonviolent offenders. One Bay Area activist told me about a particularly telling exchange, when Harris was trying to recruit her to be a staffer in the DA’s office:

“I never wanted to work for The Man,” [Lateefah] Simon says. “And she was like, ‘You’d be working for this black woman.’” When Simon demurred, Harris made her case more plainly: “You can bring your advocacy into the office, but do you forever want to be on the stairs yelling and begging for people to support you, your cause? Why can’t you fix it from the inside?”

Back on Track was successful—the recidivism rate for graduates was 10 percent, compared to 50 percent of the population as a whole, according to an op-ed Harris wrote for HuffPost. The program was later replicated in a handful of places and became a cornerstone of Harris’ own narrative; it was even the focus of her first book, Smart on Crime.

Back on Track is also a significant part of Harris’ work to rebrand herself as a “progressive prosecutor.” Her recently published memoir, The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, attempts to introduce her story to the American public. Harris writes that she is fundamentally opposed to “false choices”—including that between being a hard-nosed prosecutor and a black woman whose experiences have taught her about the need for meaningful reform. “We must speak truth about predatory corporations that have turned deregulation, financial speculation, and climate denialism into greed,” she writes. “And I intend to do just that.”

But some truths are harder to swallow than others. Harris has often been dogged by criticism from former staffers that she is too hard-driving and sometimes aloof. That assessment wasn’t helped by a series of reports late last year from the Sacramento Bee that one of her closest and longest-serving aides, Larry Wallace, was named in a sexual harassment suit filed by a former staffer at the California Department of Justice, which at the time was led by Harris.

The former staffer, Danielle Hartley, alleged that Wallace made her perform a series of demeaning tasks, including crawling on her knees to refill an office printer placed beneath his desk, often in front of Wallace and other male staffers. The case was settled in 2017 for $400,000. Wallace resigned as soon as the suit was made public last year, and Harris, a vocal advocate of the #MeToo movement, denies knowing about the settlement—a claim that was met with widespread skepticism. “Part of being an elected official is not only taking strong political positions and executing them fairly, it’s also being able to manage the people you entrust with responsibility,” the Sacramento Bee editorial board wrote late in 2018. “In this case, Harris has fallen short.”

For now, supporters are hopeful that Harris can rise to the occasion against Trump and a host of Democratic challengers, including Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, and other likely contenders including New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and former Vice President Joe Biden.

“My entire career has been focused on keeping people safe. It is probably one of the things that has motivated me more than anything else,” Harris said on Good Morning America. “When I look at this moment in time, I know that the American people need someone who is going to fight for them, who is going to see them, who will hear them, who is going to care about them, who will be concerned about their experience, who is going to put them in front of self-interest.”