Central American migrants who traveled in a caravan to the Mexico-US border gather at the entrance of a temporary shelter in downtown Tijuana on December 17, 2018. Guillermo Arias/Getty

When staff at the Tijuana office of Al Otro Lado finish making a phone call on the organization’s main line, they unplug the phone. It’s a new rule. The office phone has to be off the hook because they don’t want to get any more death threats.

It began with staff members being followed. Then their cars started getting broken into, and documents were stolen out of them. Later, the threatening phone calls began. On January 18, a caller demanded to know the whereabouts of a particular asylum-seeker, saying that if Al Otro Lado didn’t provide that information, everyone in the office would be killed. That same day, a woman delivered a note warning the organization that all of its staffers in the office were in danger.

By February, the situation had gotten so dire that Al Otro Lado sent a letter to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights asking for emergency protection. The petition included a letter of support signed by more than 40 US and international immigration law professors and lawyers calling the threats “deeply troubling.”

Listen to Fernanda Echavarri describe the spike in threats against people trying to help migrants, along with other stories from her recent reporting trip to Tijuana, on this week’s episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

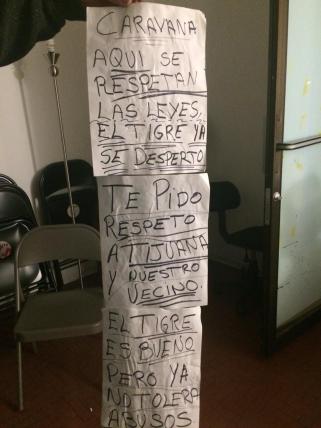

Al Otro Lado, Spanish for “on the other side,” is a Los Angeles-based legal aid organization that helps migrants, deportees, and refugees in Tijuana, Mexico. Like several other Mexican cities along the border, Tijuana has seen a surge of Central American migrants fleeing poverty, violence, and persecution, beginning with the first migrant caravans last fall. Al Otro Lado is the most prominent migrant aid group operating in Tijuana, and its work has angered some locals who resent the influx of migrants. Several Tijuana residents have posted threats on its door.

But some of the threats are coming from a more nefarious source than peeved locals. Nicole Ramos, co-director of Al Otro Lado, says many of the people the organization helps are fleeing organized crime and drug cartels in Central America and Mexico. “Organized crime understands that we are providing free legal orientation to asylum-seekers fleeing [that], so they come here to stake out the place to see who’s coming for services.”

Courtesy Nicole Ramos

“Our office is in danger,” she says. But its doors are still open. In fact, they haven’t closed at all since November, with staffers working around the clock to assist the growing number of migrants. On a recent weekday afternoon, there was a line out the door. Some people were waiting to sign up for a free legal clinic. Dozens of families were there to get medical help and food. Migrants speaking French, Spanish, and indigenous dialects were seeking guidance on how to navigate the process of seeking asylum—as Ramos puts it, Al Otro Lado informs them “what their rights are and how state actors may seek to violate those rights.” This was how it had been since the caravans. In the last four months, Al Otro Lado has helped more than 2,000 migrants in Tijuana.

Inside Ramos’ office, staff came in and out every few minutes. Her cellphone didn’t stop buzzing. “It’s nonstop,” she said as she typed on her laptop.

Ramos is one of three co-directors of Al Otro Lado, but the only one able to work in Mexico today. In late January, co-directors Erika Pinheiro and Nora Phillips were denied entry to Mexico from the United States and told that a foreign government had placed a “migratory alert” on them.

ALERT!! Our Legal Director and Litigation Director have been REMOVED from Mexico. Apparently the US govt issued security alerts on our passports to prevent us from traveling. Our Legal Director is being returned on a flight that lands at LAX terminal 2 at 12:10. Please SHOW UP

— Al Otro Lado (@AlOtroLado_Org) February 1, 2019

On January 29, Pinheiro was attempting to walk to Mexico through the San Ysidro port of entry near San Diego when Mexican immigration officials stopped her. Two days later, Phillips was detained by Mexican immigration officials at the Guadalajara airport when her flight landed. They both returned to the United States and still haven’t been told which government placed the alert on their passports.

Ramos doesn’t know if there’s also an alert on her passport, but says her attorneys are looking into it. “I don’t know if I leave Mexico whether I will be able to enter, so I have remained in Mexico during this time,” she says.

Around the same time that Pinheiro and Phillips were denied entry, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported on harassment of journalists by US and Mexican border officials. When Matthew Whitaker, then acting attorney general, appeared before the House Judiciary Committee on February 8, he was asked whether the US government keeps a list of immigration activists, lawyers, and journalists.

“Does the Department of Justice have an immigrant advocate watchlist?” Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas) asked. “Did the DOJ have anything to do with flagging these passports?” Whitaker said he was not aware of that but would get back to Escobar’s office with an answer. So far, Escobar’s office hasn’t gotten a response.

It’s not new for activists and immigration lawyers to get pushback from US immigration officials, Ramos says, but President Donald Trump’s administration has escalated that pushback into intimidation and harassment.

“These attacks on us as attorneys and human rights defenders [are] a creature of this administration,” she says. “It was not until this administration that I actually was first threatened by a [Customs and Border Protection] supervisor at the San Ysidro port of entry to have me detained and removed from the port of entry by Mexican officials. That did not happen under the previous administration.” She adds, “This is a way to silence us. This is a way to intimidate us. This is a way to make our work unbearable.”

Together with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the American Civil Liberties Union, and other organizations, Al Otro Lado has filed multiple lawsuits against the Trump administration since 2017. The most recent suit was filed last month. Ramos believes her organization has become a bigger target because of these lawsuits.

CBP did not respond to questions about alleged harassment at the San Ysidro port of entry, instead providing a statement saying, “CBP strives to treat all travelers with respect and in a professional manner.” Officials with Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Migración, the country’s immigration authority, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.