The US Coast Guard boards a Haitian refugee boat in 1992.Jacques Langevin/Getty

In October 2013, 368 mostly Eritrean migrants died after their ship sank off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa. Italy recognized them with honorary citizenship and a memorial broadcast on state television. The 155 survivors were detained in an overcrowded holding center and excluded from the ceremony to honor the dead.

The incident, recounted in Refuge Beyond Reach by David Scott FitzGerald—an essential overview of how countries across the world evade their obligations to asylum seekers—captures one of the central features of contemporary asylum policy: Wealthy democracies generally want to be seen as defenders of people fleeing persecution, but in practice they do almost everything in their power to keep people off their soil. That matters because a person must be inside a country that offers protection to be eligible for asylum. President Donald Trump has taken things even further by arguing that the United States should simply turn away asylum seekers who are fortunate enough to reach the United States.

I spoke with FitzGerald, the Gildred Chair in US-Mexican Relations and co-director of the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies at the University of California-San Diego, to understand the many ways the United States and allies prevent people from claiming asylum. Oxford University Press published Refuge Beyond Reach on Friday.

Mother Jones: You write that for 99 percent of refugees, their only option is to seek asylum. Why?

David FitzGerald: Most refugees are in the developing world. They’re in poor countries that are neighboring a conflict country. They’re often stuck in camps or they’re stuck in urban areas where they’re not allowed to work. More than 8 out of 10 refugees in the world are stuck in places like that. In any given year, fewer than 1 percent of them are resettled through a formal resettlement program like the US and Canada have.

In very few cases is it an option for someone to go to an embassy and apply for asylum. That’s something that only a handful of high-profile dissidents can take advantage of. If you’re a run-of-the-mill refugee, that’s not an option. That leaves you with trying to get to a country, whether it’s legally or illegally, and then asking for asylum.

MJ: It can be incredibly dangerous for asylum seekers to reach the United States or Europe. How do rich democracies makes those journeys necessary?

DF: People often ask this really legitimate question: “If you’re a refugee, why wouldn’t you just go some place legally?” The answer is that governments have made it really difficult for people from countries that produce a lot of refugees to get a visa to travel legally. If you’re from Somalia or Afghanistan it’s almost impossible to get a visa to travel to most countries. That leaves people with the option of traveling illegally using a people-smuggler. Then they’re tarred as illegal immigrants. That leaves a bad taste because a lot of folks think, “Well, if they were legitimate refugees, they wouldn’t be traveling illegally.” But the system has been designed so that for most people the only way to travel is to travel illegally.

MJ: Your book provides a comprehensive look at the catch-22 wealthy countries create for asylum seekers. To paraphrase: We’ll give you some due process if you get to us. But we’re going to do everything we can to prevent you from doing that. As you write, the cumulative effect of these policies shocks the conscience. Why do they get so little attention?

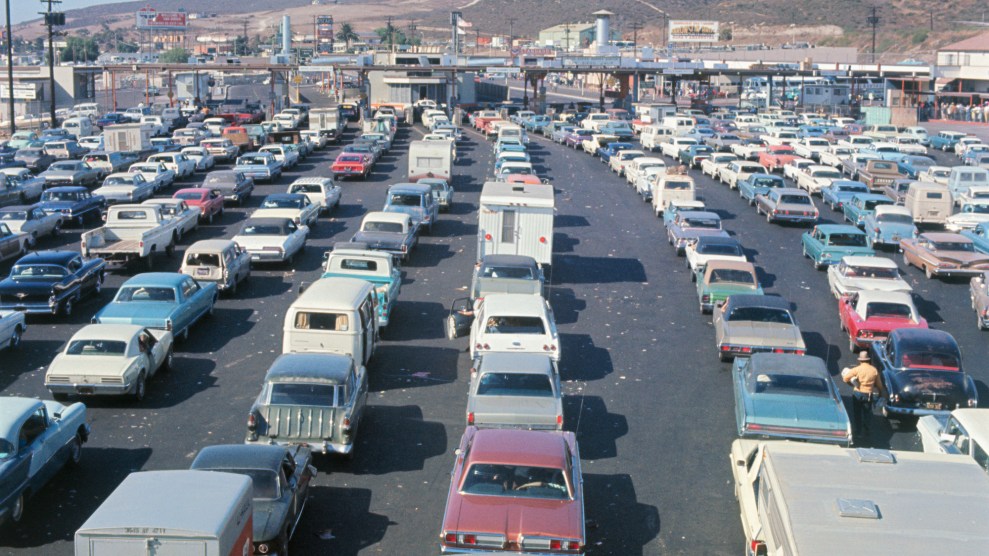

DF: Most pieces of this system that keeps out asylum seekers are invisible. I think a lot are invisible by design. Usually when people think about border control, they think about a wall. That’s not something that began with Donald Trump. I live in San Diego. I can go down just a few miles from my house and I can look at the border. What’s invisible and affects a lot more people is this system in airports, or in consulates where [visa] decisions are made behind closed doors. These interceptions at sea take places dozens or sometimes hundreds of miles from our coasts. Governments of rich democracies are paying these buffer countries to do the dirty work of interception out in the deserts or jungles. We simply don’t see what goes on. What I tried to do in this book was to show how all of these different elements work together to make it almost impossible for legitimate refugees to ever reach sanctuary.

MJ: Your book makes very clear that this is not just a US issue. You write about interceptions of refugees in the Mediterranean. What have the consequences of those interceptions been?

DF: The governments of the European Union—like Italy, Spain, and Greece—have been conducting all kinds of interceptions in the Mediterranean for the last 20 years or so. The death toll has been extraordinarily high. We can never know exactly how high the death toll is because a lot of boats just disappear. One of the perverse things about the system of control [in Europe] is that it’s undermined the basic principle of the law of the sea, which is that mariners are obligated to give aid to other mariners in distress. Because a lot of the ship crews that have rescued people at sea have been prosecuted by the Italian government, in particular, it has created a disincentive for mariners passing through those waters to help people who are drowning. We know that the result is that those people are being abandoned to drown.

The other dark side of the episode is that the Italian government is basically paying the same people-smugglers who were smuggling asylum seekers and other migrants across the Mediterranean to keep them bottled up in Libya in horrific conditions. All kinds of videos have emerged of people being tortured. I don’t use torture lightly. I mean people having molten plastic dripped onto their bodies and medieval tortures of people who have committed no crime other than simply trying to cross the country to reach Europe.

MJ: The 1951 refugee convention was written at a time when the guilt about failing to protect Jews fleeing Nazi Germany was much more raw. Do you think countries would adopt that framework again?

DF: I think that if rich democracies were to start from scratch, they would weaken the rights even more than they already are—in part because the sense of moral failure and outrage over leaving European Jewry to die in the Holocaust, the historical moment of the Cold War to use asylum policy to shame the Eastern Bloc countries that were the origins of a lot of asylum seekers, those have changed. The legacies are still with us because countries signed laws, and laws are sticky. But very few Holocaust survivors are still around. The knowledge of what happened is getting thinner. At some point, that’s going to become ancient history and won’t have the same moral resonance that it did in 1951. So I’m fairly pessimistic.

MJ: What are some of things you would do to create a better asylum and refugee system?

DF: The first thing I would do is dramatically increase the legal paths to entry for people who meet the refugee standard. What’s going on right now is the exact opposite. The refugee resettlement program in the US has been slashed.

And I would make the immigration judges who decide cases fully autonomous. For people who don’t work in this area, it’s not widely known that the immigration judges are not fully independent. They’re employees of the Department of Justice.

The third thing I would do is work with countries of transit like Mexico to be serious about providing other forms of safety. That takes a little bit of money to do, but those operations need to be fully funded. We’re going the opposite direction right now with the Trump administration constantly threatening to slash that funding.

MJ: Many people are talking about a humanitarian crisis at the border right now. Your description of the United States threatening to invade Haiti in 1994 to successfully force out the country’s de facto leader stuck with me.

You write: “The mobilization inadvertently belied the US government’s claim that it did not have the capacity to screen thousands of Haitians for asylum claims. A state that could seize a foreign country and its population of 7.6 million overnight could surely process asylum claims if it had the political will.” What lessons does that mobilization hold today?

DF: At any given second, the US government doesn’t have the capacity to do a lot of things. But when it wants to do something it can really quickly stand up the capacity. This is the wealthiest country in human history. We have the technical capacity to move hundreds of thousands of troops around the world in fairly short order. The idea that we don’t have the capacity to deal with people asking for asylum, I think is simply false. Maybe on day one you don’t. But if you care about it, within a few weeks, the capacity would be developed to do that. The fact that we don’t have this system that is able to effectively process asylum seekers and determine which of them have legitimate claims is a failure of political will.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.