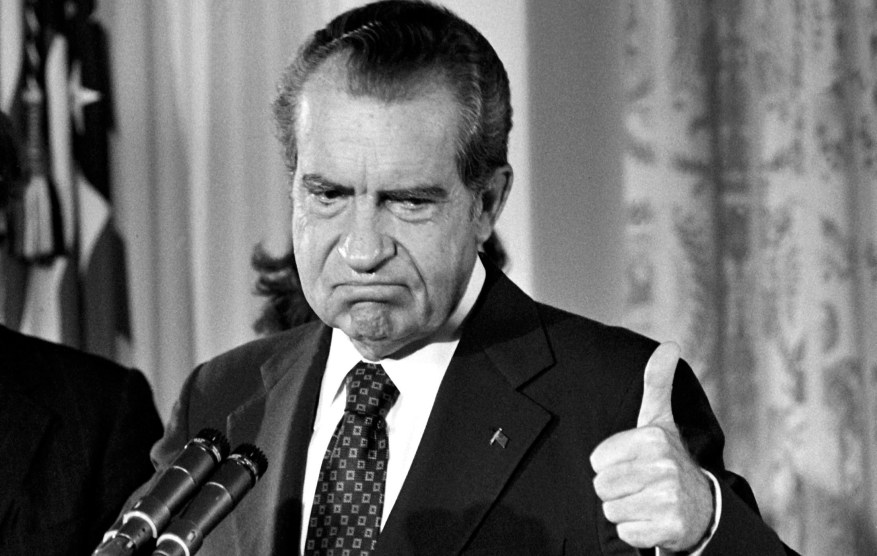

Arnie Sachs / AP

Forty-five years ago, Richard Nixon became the first president to resign from office.

Popular culture has been suffuse with Watergate remembrance for decades. (There are at least nine films about the scandal.) But neither the cinematic versions of Watergate nor the revisionist histories like Slate’s Slow Burn podcast have quite pinned down how Nixon’s dramatic exit from the White House changed America like writer Rick Perlstein. In Nixonland, a sprawling historical account that spans 800 pages, he traces Nixon’s rise and, as the subtitle puts it, “the fracturing of America.” Perlstein’s tome leaves the reader with the eerie feeling that they have just read a ghost story about a poltergeist currently haunting their own house.

The “silent majority” of angry white suburbanites, rising nationalism, and the misdeeds of a president all swirl then as they do today. Now, some within the Democratic ranks are pushing hard for the impeachment of President Donald Trump; others, like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, decry impeachment as imperiling Democrats’ shot at the White House in 2020, if not shattering the reputation of the party altogether. The debate often hinges on preserving “norms” and “institutions.” Watergate’s legacy regarding those is surprisingly murky. Did Watergate destroy our trust in Washington? Or did it affirm our faith in the government to throw out crooks?

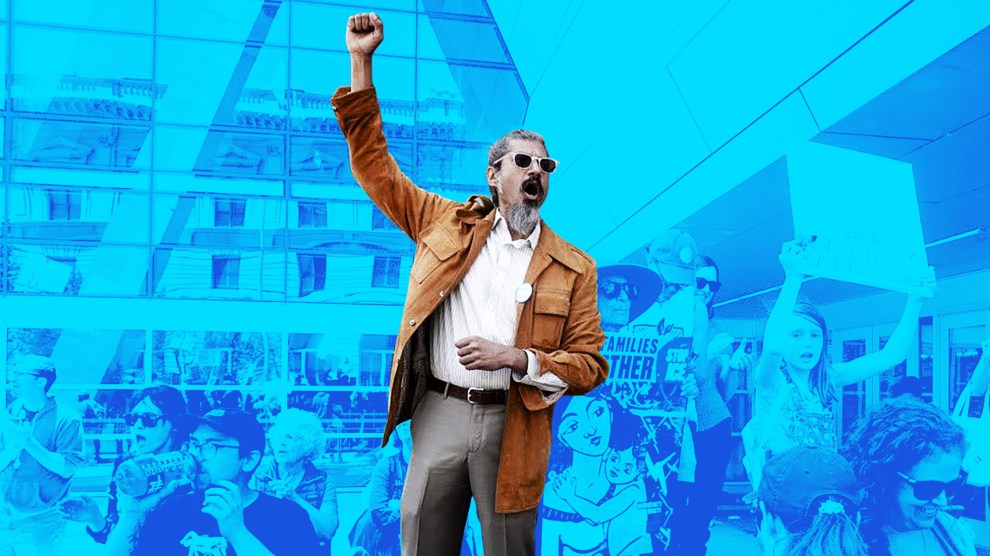

Mother Jones called up Perlstein to discuss Nixon’s resignation and what the Watergate scandal means in a moment in which “impeach” is never far from the headlines.

What was the day Nixon resigned like?

The first thing to understand is how impactful this was—that this had never happened before.

We live in a post-Watergate era. We harbor the possibility in the back of our minds that our leaders just might be criminals. They might be lying to us; they might be corrupt. That image was not the image that people had in their minds of their leaders going into Watergate. People just kind of trusted and respected their leaders in a way that was impossible after Watergate.

So I think while it was a moment of intense joy and celebration for people who had despised Richard Nixon ever since he first ran for Congress in 1946 by red-baiting a very beloved incumbent, for a sizable portion of the public, it was traumatic. For a more sizable portion of the population than was apparent at the time, it was traumatic for a completely different reason: It felt somehow the liberals were kind of putting one over on the rest of the nation and reversing the results of the 1972 election. In retrospect, the kind of things they were saying then—about this liberal coup to unseat a popular president—sound a lot like what you hear on Fox News now.

How were folks talking about Nixon’s resignation then?

Well, there’s a very famous story involving a right-wing congressman named Earl Landgrebe from Indiana. He was an outlier, kind of a right-wing nut, and most famous before that point for smuggling Bibles into the Soviet Union.

He went on the Today Show, one of the most widely watched shows, after the release of what was called “the smoking gun tape“—which, to make a long story short, proved that Richard Nixon had baldy lied about something he said he would never lie about—and he starts complaining about how this is a witch hunt. The reporter says, “Well, what about this fact? And that fact? And this fact, and that fact? What about the smoking gun tape?” And Congressman Landgrebe says, “Don’t confuse me with the facts.”

So that kind of brazenness—sort of fake news brazenness—was very unusual at the time, but you began to see the first inklings of it. Earl Landgrebe became a national joke. Now, that would probably lead to congressional leadership.

There seems to be a fundamental difference now in that we have Fox News.

Well and, of course, in a lot of ways [Fox News] was a product of that atmosphere in the early 1970s.

In the 1968 campaign, Roger Ailes [who was “Nixon’s executive producer for television”] basically came up with the idea of a Republican/conservative news network and began laying down the foundations to create one.

What are the effects of Watergate that sometimes get ignored?

Well, one immediate effect of Watergate was a strong increase in public esteem for the media. If you look at a lot of popular movies from the mid-’70s—not just All The President’s Men, but also movies like The Parallax View—basically, the indefatigable kind of anti-establishment, truth-telling investigative reporter suddenly becomes a popular American hero, like the cowboy or the detective. Every reporter wants to be the next Woodward and Bernstein.

Now that had an unintended consequence: A lot of reporting that happened after Watergate elevated picayune scandals to world-historic importance. That caused a little bit of a backlash against the press. There was even this soul-searching and reckoning within the establishment: “have we gone too far; maybe it’s not our job to be taking down presidents.” You see Katharine Graham, the owner of the Post, who is this rightly celebrated figure in the movie about the Pentagon Papers and in All the President’s Men too, worrying, “Wow, maybe we’ve created this toxic level of distrust about Americans institutions.”

Then you begin to see a quantum increase in false equivalency: we were mean to this Republican president, so we better be pretty darn tough on this Democratic president too. Now, a lot of that was cynical. One of the projects of the Nixon White House, prior to Watergate, was to basically instill this sense of guilt among the media elites—that they were biased against Republicans, that they were were biased against conservatives. This was a big project of Nixon staffer Pat Buchanan and Watergate felon Charles Colson. The administration wrote a famous memo saying, “Look, we’ve been going after these media organizations with the shotgun, let’s go after them with the rifle instead.” The administration famously tried to pressure the Washington Post to go easy on Richard Nixon, threatening to revoke licenses for the television stations they owned.

And that worked. After Nixon resigns, both Pat Buchanan and Nixon’s former speechwriter William Safire become columnists. Both of them are very aggressively pursuing this narrative that “Oh my God, if you only knew what John F. Kennedy was up to, Watergate wouldn’t seem like such a big deal!” And William Safire did something very cunning. He was a former public relations executive; he actually literally wrote a book in the early 1960s about how to use public relations techniques to manipulate the public. One of his strategies after Watergate was to take Democratic scandals and fix the suffix “gate” to them. There was a scandal involving this Korean influence peddler, who was secretly working for the Korean CIA without the knowledge of these congressmen who were taking his favors and taking his gifts. William Safire called that “Koreagate.” Before that, Jimmy Carter had a good friend, his budget director, Bert Lance, who was involved in shady banking practices. He called that “Lancegate.” With four strokes of the typewriter keyboard he was able to taunt the rest of the press and say, “Well, you paid so much attention to Watergate. Why are you giving Jimmy Carter a pass on ‘Lancegate’?”

The “gate-ification” of all these scandals seems to have confused the politics of the impeachment process. When is it justified? Is it possible to push for impeachment without playing politics?

Well, I think that for certain Republican partisans the idea became [after Watergate] that the Democrats used extra-democratic means to take down a Republican president. And of course, this was a profound misinterpretation of what really happened. The investigation was not only a truly bipartisan process—the most aggressive pursuers on the Watergate committee in the Senate were two Republicans, Howard Baker and Lowell Weicker—it was also trans-ideological. The guy who was the head of the Watergate committee was Sam Ervin, who was very conservative.

The difference between Watergate and our current political culture is that we’re accursed with these so-called institutionalists. We have special prosecutor Mueller who, famously, is obsessed with coloring only within the lines that are drawn for him. We have Nancy Pelosi, who is loathe to be seen as breaking any of the norms. But if it weren’t for people who are willing to be anti-institutional, Richard Nixon might still be president.

A lot of liberals are frustrated because they feel like Donald Trump is not getting the sort of investigation that his crimes deserve—that people are so obsessed with the appearance of propriety that they’re helping the malefactors get away with injustice. I think a lot of that intuition is correct. I think that’s one of the things the story of Watergate teaches us.

I think you’re pointing out something that we often don’t hear about Watergate. It was not as simple as American institutions working perfectly to stop corruption. Institutions also had to be made malleable by people.

It’s like that famous idea by Edmund Burke: In order to preserve an institution, you must be willing to change it.

There was that kind of creative energy in the air. It took a lot of moral courage on the part of people who basically had faith in the Constitution to say, “Look, this compact can survive, but we have to be willing to take some risks.” Of course, the last chapter of Watergate was Gerald Ford, the next president, pardoning Richard Nixon for any crimes he may have committed since becoming president. It was seen as this magnanimous act of preserving institutions, but really it was this resounding announcement that Ford didn’t have a faith in one of America’s fundamental institutions, which is the judiciary. He didn’t let the system work.

Do you think that’s been a prelude to what’s happening now then? You’ve written before about how Ford’s pardon hurt the nation rather than healing it.

The only way out is through. If there’s a breach, you have to acknowledge the breach. Basically, Ford’s pardon set a pattern for American elites and particularly Republican elites. If you fold in the way that America criminal bankers were able to get away with destroying the economy, what we have is this precedent set by Gerald Ford that America’s most powerful institutions are too big to fail—they’ll be protected no matter what. I think each successive generation of Washington malefactors has gotten that message. And it’s just gotten worse and worse with each generation.

Do you think Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats have learned the right lessons from the Watergate saga and Ford’s pardon?

I think that the lesson that she has not been able to learn from Watergate is that true patriotism takes risks, and justice requires disruption. You have to risk a great deal of dissonance and acrimony if you really want to achieve something resembling genuine healing.

When we look at the way the hearings have been held regarding Trump’s misconduct, what strikes you as different?

Well, let’s not place all the burden on the feckless Democrats, right? The biggest difference is that Republicans felt compelled to honor the legal process during Watergate.

And frankly, the media gatekeepers felt somewhat compelled to do the same thing. There were no articles—like you see now with Hope Hicks—saying, “John Mitchell faces a big decision. Will he honor congressional subpoena or not?” There was a grasp that the law is the law, and the Devil take the highmost.

One of the fascinating cultural ironies of Watergate was that this guy who had won election and then re-election on this platform of law and order—who was surrounded by these guys with crew cuts who upheld their own self-image as basically officers of the law, who revered following the rules—turned out to be one of the bad guys who was spitting on the law. And the good guys turned out to be these young, often mildly countercultural, legal staffers for the Watergate committees who basically were the villains with the long hair in the law-and-order narrative.

I got that feeling watching the video of Nixon’s resignation. It was as if this obsession he had with appearing to be a law-and-order American was the only thing that stopped him from trying to stick it out. He has his tie tight, he wants to look proper. Trump doesn’t have that.

I think that when the chips were down, Richard Nixon understood that his only alternative was surrender to the law—which wasn’t always something you could take for granted.

In the days before that resignation, according to Bob Woodward, the Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger told the generals that if the president orders something crazy—in other words, tries to keep his office by force of arm—that they were to call him first before following the order. And before that, during the first debate within the House Judiciary Committee on articles of impeachment, they had to clear the hearing room because there was a rumor that a plane had taken off from National Airport that might be preparing to smash into the capital. That’s the level of fear that this guy had inspired.

Ultimately, it turned out that the law prevailed. But only because people—meaning Richard Nixon and the people around him—were willing to uphold the Constitution and not the doctrine of brute force. That’s the awful reckoning we’re facing now with Donald Trump.

If the Watergate scandal were to happen today, would there be a resignation?

I think politicians ultimately are constrained by the political and social and cultural context of the world they operate within. If Richard Nixon had the opportunities that Donald Trump had to shape an alternate reality, maybe he would have taken them. If Donald Trump had been president in the world of a media that upheld some modicum of dignity, maybe he wouldn’t have been able to get this far.