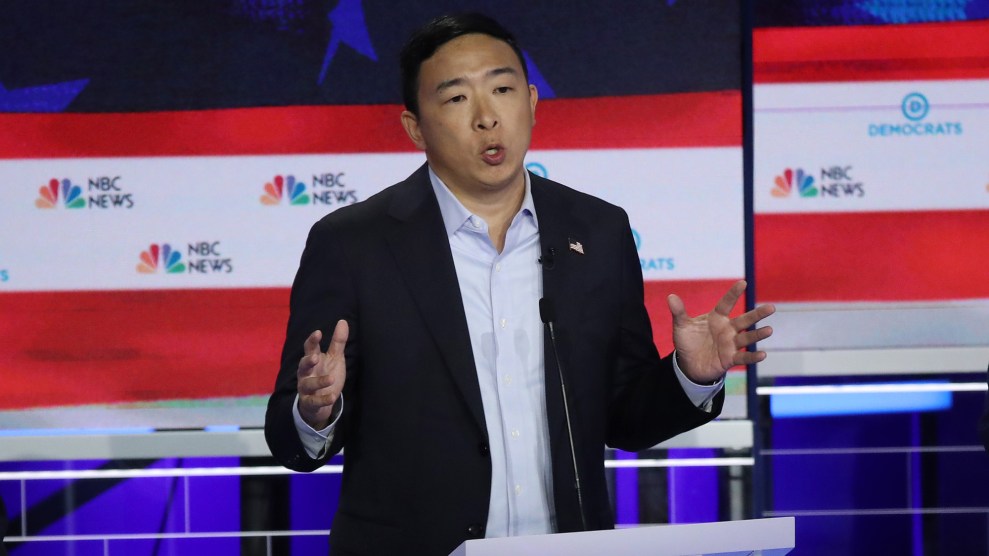

Win McNamee/Getty Images

After the first set of Democratic presidential debates in June, Andrew Yang dominated several online surveys asking who won the contest. He came in first in one run by the conservative news aggregator Drudge Report, another run by the Washington Examiner, and second in one on NJ.com. The results seemed like a stroke of good fortune for an outsider candidate with no political experience, and who had barely qualified for the June 27 event.

But the results, of course, were the outcome of a manipulation campaign by Yang fans, orchestrated by a chat group that’s home to a devout, extremely online contingent of supporters of the entrepreneur turned universal basic income backer. Together, they’ve built out a robust digital operation designed to influence conversations about Yang—one that seems unrivaled by any grassroots effort pushing other, far-higher polling candidates.

“Boost this,” one user posted in the largest pro-Yang chat hosted on Discord, a messaging app, linking to the Drudge Report’s post-debate survey. Other users of the board, which counts over 3,000 Yang supporters, posted the link, and Yang climbed to the top spot, ultimately winning the survey.

While the link was also boosted by Yang fans on Reddit and 4chan, the Discord server’s activity demonstrates that it plays host to the most developed and organized group of online grassroots Yang supporters. The group’s effects can be seen far beyond such surveys, as they work to respond to and adjust conversations about Yang playing out on social media in real-time. Before each of the party’s debates to date, a Discord group moderator has sent out suggested hashtags for members of the group to post on Twitter, helping ensure pro-Yang tweets will trend and be seen by more users. Their efforts appear to be working: The hashtag they came up with for the second debate in July, #ReturnOfTheYang, has been tweeted over 10,000 times according to RiteTag.

Before that July debate, a moderator in the group posted a link to a shared Google Drive full of infographics pushing Yang policy positions along with pro-Yang memes parodying Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and other pop culture works. “We NEED to be using the infographics from here,” the moderator wrote. ”They will allow us to flood the Twitter with the relevant points that Andrew makes.”

The group has also organized support for Yang apart from debate nights. In July, when Yang appeared on the daytime talk show The View, a moderator posted to Discord encouraging users to push the hashtag #YangOnTheView to make sure it trended on Twitter. They also organize around non-debate surveys. When the Democratic message board Daily Kos hosted a poll in late August, a Yang Discord member posted it, helping drive 8,522 votes, or 59 percent of the total participating. No survey is too small to be safe from the Yang Gang’s manipulation: The group ran up the numbers on an informal poll being conducted by a college student using Twitter replies. Within an hour Yang had 71 votes—more than doubling second-place finisher Beto O’Rourke.

Kayle Jellesma, a Yang campaign social media manager, downplayed the Discord’s effect on such surveys, saying she believed such numbers were likely driven by Yang enthusiasts on Twitter.

While Jellesma says the campaign takes a hands off approach to the Discord—”They run it themselves. We’re not involved.”—she admits the campaign is appreciative of their efforts, keeps in touch, and sometimes takes steps to support their work.

“I have connections with people who are running it. Mostly we talk about what they’re working on and what they’re doing. If we have a clip from Yang event, and they’re looking for new content for their memes, then we’ll send it to them,” she says. “The Yang Gang does it on their own. We don’t have to point them in a direction, they’ll guide themselves.”

The Discord provides other evidence of links with people on the campaign. Members of the group have discussed a May video chat with “Carly,” two months ahead of the first debate. (The Yang campaign’s deputy chief of staff is named Carly Reilly.) Andrew Juan, who according to his LinkedIn helps run volunteer outreach and engagement efforts as an intern for Yang 2020, often posts updates in the chat and was formerly one of the Discord’s moderators. (Today there are about seven moderators, who have special abilities to police the channel.)

Juan frequently posts positive, rallying messages to members of the Discord. After Yang’s first debate performance netted mostly negative reviews, he tried to shine light on a silver lining.

“This is not a loss for us,” he wrote to the group. “Andrew went up on stage and he let them scrap it out, they made themselves look like over aggressive politicians who cut each other off and refuse to listen to what others had to say.”

Campaigns have traditionally used technology not only to spread carefully crafted messages online, but to motivate people on the internet to do things off it, like phone bank, donate, canvass, and—eventually—vote. Users on the Yang Discord push these things too, but with its heavy emphasis on posting memes, boosting hashtags, and manipulating online polls, they are more focused on having supporters take action online. The server capitalizes on a devout core of Yang supporters to conduct a robust online effort mostly unseen in the other Democrats’ campaigns.

“Often times campaigns don’t understand how quickly internet evolves and digital communication and ‘memetic strategies.’ And so supporters will take it on themselves,” says Ben Decker, who runs the media and tech investigations consultancy Memetica. “This has kept Yang a part of the conversation, because by no means has he been a standout candidate.”

The closest relative to this section of Yang’s online support may not lie on the Democratic side, but with the GOP, where The_Donald, a Reddit message board, presents an earlier version of large scale, seemingly organic internet organizing. But that group of Trump supporters appears to operate in a messier, less organized manner, and is just as interested in spreading misinformation and online trolling as they are in propping up their candidate.

While intense internet coordination among Yang’s supporters may have helped him gain a foothold in formal polling and with small-dollar donations—and therefore put him in the debates—it has failed to power much of a rise since. After Yang first broke into the Real Clear Politics polling averages with a single percent in March, he has struggled to outpace about 2.6 percent.

Of course, Yang’s primary stall is likely more a symptom of his general viability as a candidate than of the technology his supporters have adopted. Indeed, Decker points out that losing primary campaigns have often served as demonstration labs for the power of new technology. “It started with Howard Dean,” he says. “They used tech to help coral people online. And then that opened the door with what the Obama campaign did and what Trump ended up doing.” Dean also employed an innovative online small-dollar fundraising strategy that was an ancestor of elements of President Barack Obama’s successful effort, and that later helped propel Senator Bernie Sanders’ well-funded 2016 and 2020 bids.

“There is legitimate support for Yang in places that were maybe being missed by traditional political organizations,” says Decker. “This does flip the script on how we understand less traditional social media platforms.”

Like Dean’s efforts back in 2004, the pro-Yang contingent’s digital grassroots efforts could portend what may come in mobilizing digital supporters across the country. Technology has its limits in changing the status quo, but it is generally good at making things more efficient. Future widespread digital efforts could help reach supporters who want to help a campaign but don’t necessarily want to leave their homes to canvas or phone bank. Such online supporters groups, unconstrained by geography, can attract and mobilize new groups of otherwise isolated supporters in districts the candidate may have a lock on or isn’t bothering contesting with others where they’re fighting.

While it’s unclear exactly the impact the Yang group is having, it appears to be the largest and most organized grassroots digital organizing effort of any Democratic campaign. On Discord, supporters of Tulsi Gabbard and Marianne Williamson have also established servers to organize posting memes and other content in favor of their candidates, but with follower counts in the hundreds, they’re a fraction of the size of Yang2020. Pete Buttigieg’s supporters have also made one with over 700 members, but it appears to be less active.

Whatever the actual impact of Discord groups organizing online, consultants used to judging campaign tools on their ability to move votes want to see more results.

“As young people tend to vote at a lesser rate in primaries, the question is, will all these people turn out to vote on their primary day?” said Kyle Tharp, communications director of Acronym, a left-wing digital political strategy group. “How do these online communities translate into offline support?”