Gov. Matt Bevin was praising Kentuckians as “the most hospitable people on the earth,” but you could barely make out his remarks over the chorus of boos. He was speaking in May at the Kentucky Derby’s trophy presentation, and observers would later debate whether the jeers were intended for Bevin, who polls show is the nation’s most unpopular governor, or for race officials, who had disqualified the favorite and Triple Crown contender, Maximum Security. The answer, it seemed, was a little of each.

Bevin had revved up his reelection campaign earlier that day, airing his first ad during the Derby coverage, a prime way to reach a wide swath of his state. As Churchill Downs, the site of the famous horse race, faded to commercial, viewers received one clear message: If you’re for President Donald Trump, you should back Matt Bevin. “President Trump is taking America to new heights, but it hasn’t been easy. People are afraid of change, but I’m not. Neither is the president, and together our changes are working,” Bevin said in the ad, as images of the two flashed across the screen, culminating with Bevin flashing a thumbs-up next to a smiling Trump.

For Bevin, winning a second term should be a breeze. He’s running in a state Trump won by 30 percent. Trump still gets high marks in polls there, and Republicans fully control the state government. But as Election Day nears, Bevin is flailing. In May’s Republican primary, he won just 52 percent of the vote in a race against three nominal challengers, a paltry showing for a sitting governor.

Bevin’s unpopularity appears to be less about Kentuckians rejecting his conservative agenda than voters growing tired of their governor’s unfiltered, Trumpian persona and penchant for generating headlines with ill-advised remarks. “Many Kentuckians see their governor as the personification of the state,” says Al Cross, the longtime dean of the state’s political press at the Louisville Courier-Journal and now a journalism professor at the University of Kentucky. “And this is a state that often comes in for ridicule. Socioeconomically and demographically, culturally, we get looked down on by people on the coasts. And often get made fun of. And Kentuckians are sensitive to that. They don’t want their governor to be a jerk.”

Bevin often takes to social media to spout off and pick fights with his many critics. “Boy, it takes so little to trigger a whiny liberal,” he stated in a video posted to Facebook last October. “Let the whiners whine. I love the fact that you’re this easily upset.”

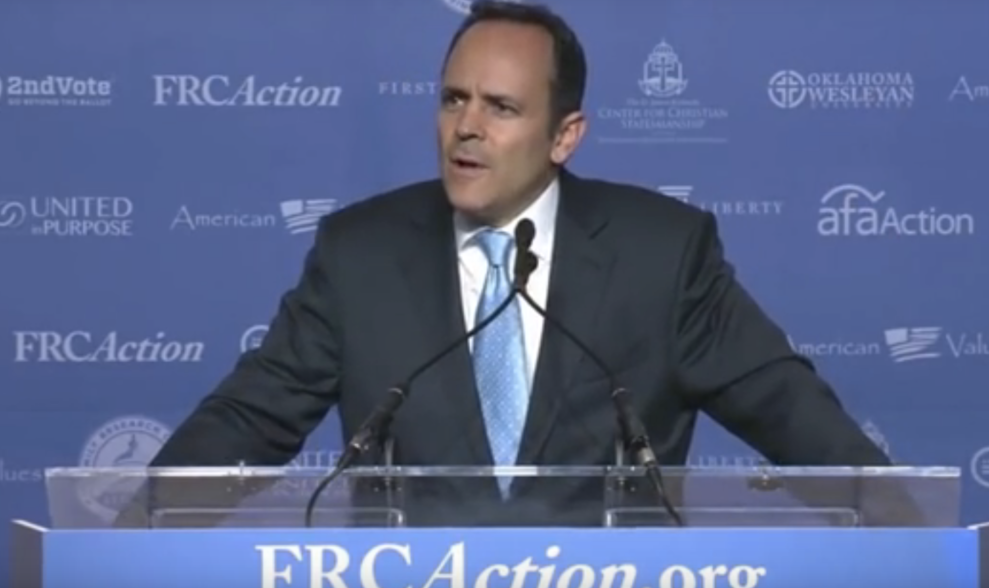

President Donald Trump steps off Air Force One with Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin.

Mandel Ngan/Getty

There has been plenty to whine about—and it’s not just liberals who have been up in arms. When Bevin visited a chess club at a majority-black and -Latino school in West Louisville, he said this activity was “not something you necessarily would have thought of when you think of this section of town.” After the Parkland mass shooting in Florida, Bevin posted a video calling for an “honest conversation”—about violent video games, films, and music. Bevin angered public health officials when, in the course of decrying government-mandated vaccines—“this is America, and the federal government should not be forcing this upon people”—he described exposing his children at a chickenpox party. Last winter, Bevin even managed to piss off Today show co-anchor Al Roker by complaining that “we’re getting soft” when a record cold snap forced school closures in Kentucky. “This nitwit governor in Kentucky, saying, ‘Oh, we’re weak,’” Roker said. “These are kids, who are going to be in subzero windchill. No, cancel school. Stop it!”

No one really foresaw Bevin’s rise. He grew up in rural New Hampshire and joined the Army before moving to Louisville in 1999 and founding an investment firm that notched him a net worth of at least $15 million, according to a disclosure he filed in 2014, when he first ran for political office. That first campaign ended in stinging defeat, as Bevin tried to ride the tea party wave and unseat then–Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. McConnell ran ads dubbing Bevin an “East Coast con man.” Bevin’s challenge died after he was caught on video at a pro-cockfighting rally.

The primary ended with hard feelings all around between Bevin and the state Republican Party. “You can’t punch people in the face, punch people in the face, punch people in the face, and ask them to have tea and crumpets with you and think it’s all good,” Bevin told Politico after he lost, explaining why he wasn’t endorsing McConnell. “Life doesn’t work that way.”

A year later he ran for governor, positioning himself as a no-nonsense businessman running against the establishment. This time, Bevin won a four-way primary by 83 votes and later cruised to a nine-point victory over his Democratic opponent. “Kentucky’s gubernatorial races so often become a predictor of the presidential election the next year,” says Jonathan Miller, a former Democratic state treasurer. Kentucky has trended Republican at the national level for decades, even as Democrats dominated state politics. (They still boast a voter registration advantage.) Bevin became the state’s second Republican governor since 1971, and with Trump atop the 2016 ticket, Republicans took control of the state House for the first time since 1921.

In January 2017, Bevin and the new Republican majority quickly set to work passing a conservative wish list: tort reform, a host of abortion restrictions, and a so-called right-to-work law that brought Kentucky into line with every other Southern state. Kentucky had seen its uninsured rate drop from 20 percent to 8 percent thanks to Obamacare, but Bevin shuttered the state health insurance exchange and now wants to add work requirements to the state Medicaid program that could result in tens of thousands of Kentuckians losing their health coverage. (Those requirements are on hold while they’re being disputed in the courts.) He’s “Scott Walker’s politics with Paul LePage’s mouth,” says Jason Bailey, executive director of the left-leaning Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

But Bevin’s pugilistic style and cringe-inducing statements are bogging down the state GOP at the very moment it has its first opportunity in a century to enact its agenda. “He has made life more difficult for himself than it probably had to be,” says Scott Lasley, a political science professor at Western Kentucky University and the 2nd District vice chair of the state Republican Party. A dispute between Bevin and his lieutenant governor, Jenean Hampton, dominated headlines earlier this summer after his administration fired two of Hampton’s aides without consulting her. “Pray for me as I battle dark forces,” Hampton, who was dropped from Bevin’s reelection ticket, tweeted after the firings. A few weeks ago, Hampton sued Bevin, arguing that the firings were illegal. Democratic Attorney General Andy Beshear (son of former Gov. Steve Beshear) has also become a persistent thorn in Bevin’s side, dragging him into court to challenge his policies. Beshear will face Bevin on the ballot in November, and Beshear’s campaign has already racked up the endorsement of one Republican state senator.

But Bevin’s biggest mistake may be spending the past two years picking fights with public school teachers. He successfully pushed a law to allow charter schools, saying he wanted to “end the monopoly that exists in Kentucky’s school system,” and he’s attempted to weaken pension benefits for public employees. Once again, Bevin piled personal invective on top of right-wing policy.

Teaches and their supporters protest attacks on public education, in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Bryan Woolston/AP

Last year, when teachers held a sick-out to protest Bevin’s proposed pension cuts, the governor unleashed an unhinged rant. “Here’s what’s crazy to me,” he told a reporter. “I guarantee you somewhere in Kentucky today a child was sexually assaulted that was left at home because there was nobody there to watch them.” (Republicans in the state House passed a resolution condemning Bevin’s comments, which he later apologized for.)

In April, Bevin said that teachers taking a sick-out day to protest his pension proposals had led to a child being shot: “One thing you almost didn’t hear anything about while we had people pretending to be sick when they weren’t sick and leaving kids unattended to or in situations that they should not have been in—a little girl was shot, 7 years old, by another kid.” (Beshear tweeted in response: “Despicable. Matt Bevin is unfit to govern. Kentucky families, teachers, and kids deserve so much better than this governor.”)

And Bevin has compared teachers and other public employees concerned about his pension plan to drowning victims. “They’re fighting you, biting you, pulling you under,” he said. “You just need to knock them out and drag them to shore.”

“This governor just keeps opening his mouth and putting his foot in it,” says Stephanie Winkler, a fourth grade teacher from Madison County who recently concluded her term as president of the Kentucky Education Association (KEA), a powerful advocacy group for educators that has tangled with Bevin. “And it’s on the minds of people. Anybody that works in a public school.”

Like many other states, Kentucky has seen a precipitous drop in education funding following the Great Recession. Teacher salaries and spending per pupil are down about 6 percent, adjusted for inflation. Alongside colleagues in West Virginia, Arizona, and Oklahoma, Kentucky teachers joined the “Red for Ed” strikes of 2018, with educators frequently descending on the state Capitol to protest. Last December, when Bevin called a postelection special legislative session to once again try to pass changes to the pension system, teachers flooded Frankfort to sing modified Christmas carols urging lawmakers to leave things alone. After less than 24 hours, legislators shut down the special session without debating any proposals.

“The professional attacks are bad enough. But then when you add on top of that the utter disdain that he has for teachers and public education in general, it’s not just a professional insult, it’s a personal insult,” Jacqueline Coleman, the Democrats’ candidate for lieutenant governor, tells me in the hallway of John Hardin High School, after addressing a crowded lunchroom of teachers at a KEA conference in Elizabethtown, a city of 30,000 people an hour south of Louisville. Coleman, wearing a bright red blazer in a nod to Red for Ed, has never held elected office before. But it’s clear why she ended up on the ticket alongside Beshear. Coleman is a former high school civics teacher and basketball coach who was working as an assistant principal until she took leave to campaign. “We are taking this personally, and rightfully so,” she says. (Davis Paine, Bevin’s campaign manager, says in a statement: “The Governor will not be deterred by KEA’s misinformation campaign and will continue to champion policies that strengthen our education system and support teachers.”)

In late July, Bevin called another special session. This time, Republicans—with no Democratic votes—passed a smaller pension cut that will limit benefits for a subsection of public employees, affecting about 7,000 people who work for local health departments, some regional universities, and a few other semi-government offices. So far, Bevin has not made any noise about restarting the debate over public school teacher pensions, but given his focus on the issue during his first term, it’s likely he would resurrect it during a second term.

“I’m concerned that if you start taking things like that away, you’re just going to lose some of that draw for the future teachers,” Josh Underwood, a high school physics and aviation teacher who is a trustee on the teachers’ pension board, told me in between checking people in at the front desk of the KEA conference back in June. “I mean, you don’t necessarily go into teaching for the retirement, but it is a consideration.”

Just before speaking with Underwood, I had met one such future teacher. Cameo Kendrick, a 27-year-old single mom and rising senior at the University of Kentucky, spends part of her time working as the president of KEA’s Aspiring Educators Program, a group of college students preparing for careers in education. Over the past several years, she’s joined the protests at the state capitol, bringing her kids along bearing signs supporting teachers. “They loved it. They came home and they were like playing with their barbies and saying little chants.”

“They know if I say, ‘Matt Bevin,’ they’re like, ‘He is mean.’”

Kendrick is full of verve and seems like just the sort of teacher Underwood was talking about schools needing. “I really believe that my generation of educators, and my generation of people in general, are really raising the generation that’s going to save the world,” Kendrick says. But our conversation ended on a bit of a dour note for the future of her home state. While saying that Kentucky needs more teachers like her from diverse backgrounds, Kendrick said she didn’t think she could handle working in a state where the governor demonizes educators, and would likely look for teaching jobs in other states after graduation: “I don’t see myself putting in a single application in the state when I graduate, to be completely honest.”

The teacher backlash poses a real risk for Bevin. According to Winkler, the former KEA president, schools are the biggest employer in most of Kentucky’s 120 counties, and more than half of KEA’s members are Republican. Last year, Jonathan Shell, the state House majority leader, lost his Republican primary to R. Travis Brenda, a math teacher fed up with Shell’s role in co-writing a pension-cut bill.

“A lot of teachers in this state are Republicans, and a lot of Republicans are teachers,” says Al Cross, the veteran Kentucky journalist. “In November 2019, teachers are going to remember what Matt Bevin said about them.”