Imagine the tycoons of Silicon Valley engineered a presidential candidate they could really get behind. He would be a man, of course. He would not be a stuffy academic or politician but, like them, a big thinking entrepreneur. He would understand online culture. He would have a slogan that would place technological progress over ideology, something like, “Not left, not right, but forward.” He would be nerdy, but also down to bro out.

This 2020 candidate, of course, is Andrew Yang.

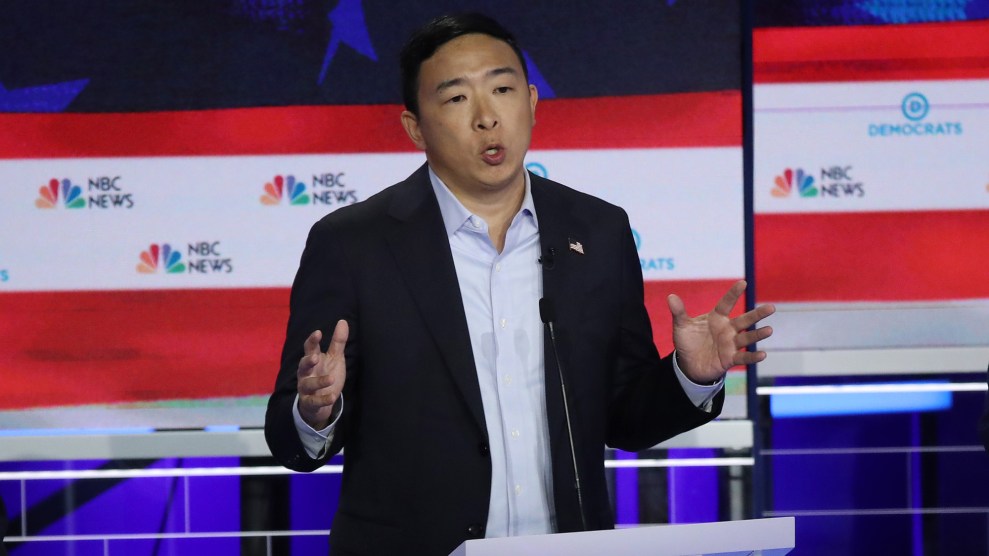

“One of the things that struck me early on about Andrew Yang was the fact that he, in the debates, wouldn’t wear a tie,” says Jessie Daniels, a Hunter College professor in the emerging field of digital sociology. “That was just so perfect. It’s like, ‘Oh, right, you’re one of those guys.’”

The missing tie is just one signifier of Yang’s tech bro identity. His supporters have flooded the internet, waging a meme-centric campaign. He has tapped into a base of mostly young men, whom his campaign targets in online advertising as its key voting bloc. He calls his proposed infrastructure workforce the “Legion of Builders and Destroyers,” which sounds like an e-gaming guild. Then there are his habits that remind us of all the bros we know: Announcing his presence in a newsroom by shouting “IT’S ANDREW YANG” in a manner that only all-caps can convey; crowd surfing; skateboarding; high-fiving; and, as he relayed in his book, naming his pectoral muscles during a period of bulking up at the gym. And there is his wardrobe, filled with staples of the valley vibe where men breeze through billion dollar decisions in jeans.

But nothing screams tech bro more than the policies behind his campaign. Yang’s platform embodies Silicon Valley’s history, its ideological outlook, and its goals of unregulated expansion. As Yang’s candidacy has outpaced or outlasted senators, congressmen, and governors, he’s endured as a tribune of tech’s values, warning about the inevitable march of technology and pushing their preferred solution to what it will unleash on society.

The most in-vogue policy in the valley may be universal basic income, and Yang’s take on the idea—the core driver of his campaign—is to send every American citizen over 18 years old a check for $1,000 every month.

Yang, like some labor economists and like many in the tech world, believes that automation caused by engineering and scientific advances—think self-driving cars and artificial intelligence—will displace millions of American workers in the next decade. To protect the country, Yang is pushing a quick libertarian-style fix to solve the threats of automation—and nearly every other societal ill along with it.

He’s not alone. Billionaires Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg have expressed support for a universal basic income; Musk has even endorsed Yang’s campaign. In Palo Alto, Stanford has a launched a Basic Income Lab. Not far away, the city of Stockton, California, is running a prominent cash-transfer pilot. Yang evangelizes universal basic income, what he calls his Freedom Dividend, as “human-centered capitalism” that would allow each individual to fulfill his or her potential through the market, not government. He argues it will lift people out of poverty and kickstart new businesses, and that with $1,000 per month in their pocket, cash-strapped Americans will be less likely to blame immigrants and racial minorities for their struggles. As sea levels rise, he has said, the money could help people relocate to higher ground. He’s also suggested it as a cure to educational inequality, claiming the $1,000 per month will help poorer school districts, just as soon as the money is reflected in local property tax receipts.

Yang describes himself as the ambassador for this panacea. “I’m, like, hanging out with the tech wizards of Silicon Valley, and I’m like, ‘Hey, you know, are we gonna automate these jobs away?’” Yang explained during a February interview with podcaster Joe Rogan, relaying what may or may not have been an actual conversation with actual tech savants. “And they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, we’re gonna automate these jobs away.’”

“Whose responsibility then is it to go tell the people, ‘Look, it’s technology, it’s transformed the economy in fundamental ways, and we need to make it so that everyone benefits and it’s not just…this hyper-concentrated set of winners and this like huge army of relative losers.’” Yang asked. “It’s the government’s job. But at this point, we’ve given up on our government as anything—like, it can’t really do anything. And so now it’s no one’s job.”

“And so somehow, Joe, it has become my job,” Yang said. “And it blows my mind too, sometimes.”

For all of Yang’s temperamental and ideological alignment with the Valley, he’s recently ramped up attacks on some of the online economy’s giants, as could be seen one chilly November evening, as Yang commanded an audience of nearly 2,000 gathered at Northern Virginia’s George Mason University. In his trademark MATH baseball cap—short for “Make America Think Harder”—and with a custom stars and stripes soccer scarf draped around his again tieless neck like a holy cloth, Yang warned about “my friends in California” who are working on automation.

He took his critique of Silicon Valley further, chiding them for zapping up the country’s wealth and giving nothing back. Companies like Google and Facebook track people’s every move, Yang complained, “selling and reselling and repackaging our data over and over again, profiting to the tune of tens of billions of dollars…And we are seeing none of it.”

He singled out Amazon, as he regularly does, for hoovering up billions of dollars from Main Street stores and paying nothing in taxes. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, he mocked, thanks his wily accountants by handing out gold coins. “Then they go home and take little Scrooge McDuck gold coin baths,” he said to laughs.

Big Tech, he continued, is “actually corroding our democracy, our sense of agency and decision making.” He turned to Facebook, whose CEO was in the midst of publicly defending his decision not to remove false content from politicians. “I have to say it’s embarrassing that Mark Zuckerberg is clinging to the like, ‘Oh, we can’t decide what’s true. What’s not true. It’s too hard. Uhhhh,” he said, letting out a tortured whine to claps and hoots. “It’s freaking embarrassing.”

His speech tracked closely with his campaign’s first television ad, launched three days later with a $1 million Iowa ad buy, which portrays Yang as a progressive crusader against Big Tech. Created by the firm that worked for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign, the ad flashes a grainy, menacing picture of Zuckerberg as the narrator declares that Yang wants an “economy where Big Tech and Wall Street are held accountable”—a liberal message that echoes the talking points of Sanders or Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, both of whom rank high as second choices for Yang fans.

Last week, in the wake of the ad’s debut, Yang rolled out a set of policies to mitigate technology’s harms through guidance and, when necessary, regulation. Adding to platform planks aimed at protecting children and providing more control and transparency around how personal data is collected and used online, Yang proposed steps to combat disinformation and new principles for when to break-up monopolistic tech companies.

This new agenda is the clearest indication yet of Yang’s willingness to regulate the technology sector—including contemplating the idea that tech companies could grow too large. While most federal agencies are based in the beltway, Yang proposes a new Department of Technology headquartered in Silicon Valley, that would “spearhead public-private partnerships.” Yang’s description of the agency’s role reads like a mantra for his campaign: “Technological innovation shouldn’t be stopped, but it should be monitored and analyzed to make sure we don’t move past a point of no return. This will require cooperation between government and private industry.”

Perhaps his strongest proposal is to modify existing law so internet giants are liable for content spread on their platforms—a loss of an immunity now central to Facebook and Google’s businesses. But Yang hasn’t been specific about how he’d change the law, and his overall vision is of government and Big Tech working cooperatively, with as little regulation as necessary. On cryptocurrency, he calls for new government rules because the current patchwork of regulation “has had a chilling effect on the US digital asset market”—not because of the risks cryptocurrencies pose to law enforcement or foreign policy. Yang’s longstanding support for individual data rights falls conspicuously short of true data ownership. Rather than give people a cut of the massive profits this data is generating for big companies, Yang would place a consumer tax on digital ads—costs that will be passed on to advertisers and likely consumers.

Even as Yang acknowledges some of the havoc that Big Tech has wrought—from reshaping the economy to allowing interference in our democracy—he maintains a faith that cooperation will triumph over regulation, even as tech companies, beholden to their shareholders, perpetually aim for expansion that can conflict with the public interest.

In America, the idea of directly giving people cash to alleviate poverty draws on two distinct 20th century traditions. One, championed by ’60s-era African American activists, saw providing direct cash assistance to people in need as a tool to lift up their communities. The Black Panthers’ 1966 10-point platform included calls for a guaranteed job or income. Not long after, the National Welfare Rights Organization, made up largely of poor black women, demanded an inflation-adjusted guaranteed income based on family size. Before his assassination in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s campaign endorsed a minimum income. In recent years, progressive policy advocates, many of them people of color, have breathed new life into these policies, viewing them not as the solution to a future crisis, but to one as old as America’s racial wealth gap.

“We should scenario plan for what’s coming,” agrees Dorian Warren, co-chair of the Economic Security Project, which helped launch basic income pilots in Stockton and Jackson, Mississippi. But he argues cash assistance should aim to help “people struggling now and have been struggling for years and decades and centuries…the people in Stockton and Mississippi, for instance, they’re not affected by automation just yet. They just can’t get work now or the work they get doesn’t pay.”

The country’s other basic income tradition is libertarian, championed by economist Milton Friedman and later the conservative scholar Charles Murray. Observing the poverty wrought by the Great Depression, the young Friedman began in the 1940s to advocate for a basic income not through cash handouts but through a negative income tax. (Today’s earned income tax credit is a remnant of his efforts.) Friedman’s plan would have replaced the welfare state’s patchwork of assistance programs and instead given money to the poorest filers, shrinking government and allowing poor people freedom to spend as they wish. More recently, Murray, infamous for co-authoring a book suggesting that black people may have lower IQs than white people, argued for discarding the entire safety net—no Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, housing assistance, or other welfare programs—and replacing it with a $10,000 yearly stipend; those making over $60,000 would get only $6,500.

Yang’s plan is very close to the libertarians’. Most adults would get $12,000, but, with few exceptions, would have to forswear all other forms of government assistance, including food stamps and Social Security Supplemental Security Income, which provides money to the poor and disabled.

As his plan has received more scrutiny, his campaign has added exemptions. His website now says that people could continue to draw most Social Security and disability payments and suggests special rules for disabled veterans. But as Yang has explained, cutting people from benefits is part of how he would pay for the plan. As the cost of other government aid programs goes down, the Freedom Dividend becomes more affordable. But with $1,000 going to people regardless of their wealth or income, benefit cuts for the poor will subsidize checks destined for the rich, and poorer Americans who choose between the Freedom Dividend and existing welfare benefits will not net the full $1,000. Everyone else will. Yang has boasted that his plan will shrink the welfare state, while denigrating government’s ability to do much of anything. Sending checks to large numbers of people is one of the “only core competencies our government has that we can trust,” he told Rogan.

Yang’s press secretary, SY Lee, told Mother Jones that citizens would be able to collect their $1,000 on top of federal housing assistance, and that the extra income would not affect children’s eligibility for Head Start, the Great Society education program. Lee did not answer whether eligibility for health care programs like Medicaid or other federally-funded benefits would be affected, but confirmed that people would have to choose between food stamps and the Freedom Dividend.

“Andrew Yang doesn’t want anyone to be worse off, which is why the Freedom Dividend is opt-in, but the benefits of the replaced programs are generally under $1,000, and people on them have to deal with a degrading and paternalistic bureaucracy,” says Lee. “We should trust people to improve their lives instead of forcing them to jump through hoops for something that’s worse than cash.”

To help pay for the dividend’s remaining costs, Yang proposes a new value added tax that he suggests will somehow burden tech companies, redistributing their wealth back to the everyday people whose personal data helped make Silicon Valley rich. Yang sometimes calls his Freedom Dividend a “tech check,” implying it will be paid for by companies like Facebook and Google. “The VAT will let the American people get a slice of every Amazon purchase, every Google search, and every robot-truck mile,” says Lee. “Basic staples like food will be excluded from the VAT, while luxury goods will be subject to higher rates. The VAT combined with the Freedom Dividend is a progressive policy.”

But a value added tax does not single out tech companies or the tech industry. While Yang’s website claims his VAT will not hit consumers, this is an outlier view. “Virtually any economist would say that a VAT would be passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices in exactly the same way sales tax is,” says Leonard Burman, a tax policy expert at Syracuse University. Like a sales tax, a VAT is regressive because everyone pays the same rates; while the wealthy pay more taxes because they purchase more goods, the poor spend a higher proportion of their wealth on goods and on taxes. While a VAT is an efficient way of collecting revenue, says Burman, it doesn’t have anything to do with Big Tech.

If Yang really wanted to ensure those tech Goliaths footed the bill, taxing them would be a more direct route.

“I don’t hear any of the tech people saying tax us more,” says Warren at the Economic Security Project. “I don’t hear them saying tax our companies, I don’t hear them saying tax our data that we extract from ordinary people every single day. That’s a conversation he could be leading and he’s not. ”

“This is a wolf in sheep’s clothing type program,” says Darrick Hamilton, an expert on racial wealth disparities at the Ohio State University. While Hamilton supports direct cash assistance, he warns universal plans, like Yang’s, are inherently flawed and increase inequality, and not only by undermining the current social safety net. Poor people will spend the new money on necessities, while wealthier tax payers can save, further padding their portfolios. Meanwhile, he believes the influx of cash into the economy will cause inflation, reducing poorer people’s spending power. (Yang has denied his policy would result in inflation.)

“He captures people’s minds and attention with this notion of ‘give people resources so that they can manage their own lives and make choices for themselves,’” says Hamilton. “That’s such an appealing message. But when you get into the details of it, that’s where the problem occurs.”

The first signs of support for Yang’s candidacy came from internet subcultures who found Yang’s plan appealing for just this reason. According to Ben Decker, whose firm Memetica tracks online extremism, internet subcultures—made up of predominantly young men—were already “discussing on a pretty regular basis” ideas like AI, automation, cryptocurrency, and related topics that Yang has embraced. To them, especially those who have embraced not participating in the labor force—they call it “Not in Education, Employment, or Training” or NEET—getting $1,000 a month sounds pretty good. Yang has outlined a “technical utopia where everyone’s just given money by the government to do whatever,” says Decker.

Earlier this year, Yang tapped into this internet-savvy and largely male base of potential supporters, first in a February interview on Rogan’s podcast and YouTube show, explaining UBI between ads for a performance drink called Liquid IV, and shortly afterward in an appearance on conservative media personality Ben Shapiro’s YouTube show. New fans swarmed the campaign, helping birth innumerable memes featuring money bags, anime, and the Pepe the Frog character used by white nationalists to support Donald Trump in 2016.

Yang’s early online momentum continues to help fuel the campaign. At the George Mason University event, one attendee after another said they first heard about Yang online, many encountering him on YouTube or Rogan’s show. Kevin, a 22 year old from nearby Alexandria, explained that YouTube’s “algorithm” had sent Yang his way, illustrating how Yang’s unexpected success has been forged on the very platforms he claims are destroying the country.

Despite one of Yang’s favorite phrases on the stump—that the “opposite of Donald Trump is an Asian man who likes math”—in many ways, a dial turned 180 degrees from Yang actually points to Elizabeth Warren. Where she’s made her career as a savvy regulator, Yang shies away from new regulations. When Warren, drawing on New Deal–style traditions, called for strengthening unions and putting workers on corporate boards as a way to stanch job losses at the Fourth Democratic debate in October, Yang’s response seemed to reject the idea that government had any power to protect people from the market.

“My friends in California are piloting self-driving trucks,” he said in response to Warren. “What is that going to mean for the 3.5 million truckers or the 7 million Americans who work in truck stops, motels, and diners that rely upon the truckers getting out and having a meal? Saying this is a rules problem is ignoring the reality that Americans see around us every single day.”

When it came to Amazon, the dynamic resurfaced, with Warren calling for the online retailing giant to be broken up, alongside other big tech companies like Facebook and Google. While Yang’s stump speech chastises Amazon for extracting $20 billion in wealth from local merchants, on the debate stage Yang spoke out in defense of the company’s size.

“It’s not like breaking up these big tech companies will revive Main Street businesses around the country,” Yang argued back. “Using a 20th century antitrust framework will not work. We need new solutions and a new toolkit”—one that hinges more on cooperation than aggressive regulation.

Silicon Valley wasn’t supposed to usher in joblessness or a resurgence in white nationalism. The internet was supposed to be utopia. In February 1996 in Davos, Switzerland, John Perry Barlow downed a few glasses of champagne, flipped open his Mac laptop, and pounded out the “Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace,” promising “a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth.” This new frontier, he wrote, eschewed any government intervention or rules.

When Barlow, a rancher, Grateful Dead lyricist, and later, a crusader for civil liberties in cyberspace, died last year, Jessie Daniels, the sociologist, noticed a photo from an obituary likely taken on his Wyoming ranch. In it, Barlow is standing on snow in a coat and cowboy hat, a rifle leaning against his chest. He appears to be guarding the object perched on a fence post next to him: a late-1980s Macintosh computer.

When Yang took the debate stages without a tie, Daniels was reminded of the roots of the valley’s ethos, set out by Barlow a generation ago: masculinity, libertarianism, and manifest destiny. “Andrew Yang has been really smart and deft about the way he’s latched onto the core values in that tech bro culture,” she said.

Even before Barlow’s declaration promised a place of unencumbered freedom, the cracks in this ethos were already apparent to liberal academics. In 1995 British media theorists Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron deduced a “contradictory mix of technological determinism and libertarian individualism in Silicon Valley, dubbing it the “Californian Ideology.” They argued that the Valley’s self-image rested on a willfully ahistoric understanding of its own past by proclaiming an independence from government even as its growth had been fueled through massive subsidies, military contracts, and publicly-funded universities. “Both capitalists and well-paid workers fear that the open acknowledgement of public funding of their companies would justify tax rises to pay for desperately needed spending on health care, environmental protection, housing, public transport and education,” Barbrook and Cameron wrote. “Working for hi-tech and media companies, they would like to believe that the electronic marketplace can somehow solve America’s pressing social and economic problems without any sacrifices on their part.”

Whereas Barlow would soon declare that all entered cyberspace as equals, Barbrook and Cameron pointed out that telecommunications companies had “red-lined” minorities by failing to build the physical infrastructure to access the internet in poor neighborhoods. “The deprived only participate in the information age by providing cheap non-unionised labour,” they wrote. Twenty-four years later, Amazon workers collapse dead in warehouses while racist trolls plan neo-Nazi rallies on social media.

The inequality generated by the technology industry, apparent then, has reached dystopian levels: pockets of hyper-rich circled by the misery of San Francisco’s ballooning homeless population. Tech companies spend what amounts to a small economic stimulus on their own security details. The country’s richest are mostly tech tycoons: Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Bill Gates of Microsoft, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, Oracle’s Larry Ellison, Google’s Larry Page.

But Yang’s UBI proposal may be more of a lifeline to Silicon Valley than to the workers left behind or threatened by automation, a “shiny object” to distract people, in the words of Jhumpa Bhattacharya, a progressive policy advocate in the Bay Area. “Look, we’re giving you $1,000 a month,” she says, explaining the thinking, so you don’t “focus on the root of the problem that we’re creating.”

Inside tech, people hope UBI will be a quick fix—the ultimate hack—to solve all the problems that their industry is contributing to. “When they think about job loss, poverty, family breakup, hunger, housing—those all seem to fall into the bucket of, ‘Oh, UBI would help,’” says Jennifer Burns, a Stanford historian who studies libertarian political movements. “UBI just seems cleaner and quicker, and seems like maybe you can do an end run around all these problems with a cash transfer.”

“It’s sort of capitalism solving capitalism’s problems,” Burns continues. “If some people aren’t able to earn enough of a living within a relatively unregulated or capitalist economy, rather than change that economy, what you do is you provide them with cash. Then they enter the market on their own.”

This is essentially Yang’s vision, which he calls “human-centered capitalism.” His Freedom Dividend, he says, will lift up communities and allow people to follow their dreams. An example he uses frequently is someone who has always wanted to open a bakery. With $1,000 per month, the baker would have more startup capital and potential customers would have more to spend on muffins. That vision isn’t about making new rules for capitalism. It’s about making more capitalism.

Yang’s life story might help us understand his own love for the market. After five unhappy months as a corporate lawyer, Yang moved into the tech space in his 20s. He co-founded a start-up called Stargiving that, as Slate described it, “made small donations to celebrity charities each time a visitor clicked a button.” Yang says it fell victim to the dotcom bust. But in tech, failing can be a resume builder, and after another ill-fated start-up, Yang next served in senior positions at two New York software companies. In 2006, he became CEO of a test prep company that specialized in training students for the business school entrance exam. Revenue boomed after the 2008 financial crisis spurred many young people to wait out the recession earning an MBA. When Kaplan bought the company in 2009, Yang made millions. He was 34.

Yang says that watching the best and brightest vie for Wall Street jobs seemed like a waste, and, feeling conflicted about his own role, decided to found Venture for America. The program, like Teach for America, would place talented college graduates into start-ups in the South and Midwest. Rather than help disadvantaged kids, they’d help disadvantaged companies, training thousands of recent graduates to be entrepreneurs in economically-struggling regions. The Obama White House named him a “champion of change.”

But he says the program’s success paled in the face of the dark future he saw. “Imagine being this guy getting medals and awards for helping create jobs around the country, and then realizing that automation is coming like a tidal wave,” Yang told Rogan, “and that your efforts that you’re getting applauded for are really not going to do the trick.”

Trump won the 2016 election by eking out victories in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. There’s no single reason why: racism, Russian hacks and misinformation, the fumbles of then FBI Director James Comey, and everyday politics all played a role. But Yang sees all that as a distraction, favoring the once dominant explanation that Trump’s campaign tapped into a particular strain of economic anxiety brought on by the loss of good paying industrial jobs. “It’s a straight economic story where we blasted away 4 million manufacturing jobs in the swing states and Donald Trump is our president,” he’s said.

Technology has always changed the nature of work. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the industrial revolution spurred millions of Americans to leave their farms for manufacturing jobs in cities. This new industrial economy created the mega-rich, who profited off of poor working conditions and low wages. Ultimately, the Gilded Age, followed by the Great Depression, spurred new rules for the economy: minimum wage laws, child labor laws, collective bargaining rights, and welfare programs like Social Security. For progressive policy wonks, that era of the 20th century offers government a template for today; in what is arguably a second Gilded Age, they want new rules that would put power back in the hands of workers.

Progressives who favor a guaranteed income envision it as part of a larger program to tackle inequality. “It has to be part of an overall package of a new social contract,” says Warren at the Economic Security Project, that would include enforcing antitrust laws and taking on corporate monopolies, serious labor law reform, a $15 minimum wage, and portable benefits programs so health care and retirement security are not tied to any particular job.

But beyond his UBI, Yang offers little to address economic inequality. His website’s dozens of policy proposals say nothing about labor or unions. The fix isn’t new laws to protect unions, he has said, it’s $1,000 per month. Yang has said he hopes the money will quell worker unrest, and prevent strikes and riots like the bloody clashes of the 19th and 20th centuries that helped spur the creation of today’s worker protections. “It’s like smoke and mirrors,” says Bhattacharya, who advocates for cash assistance at the Oakland-based Insight Center for Community Economic Development. “It’s designed to distract from the larger labor policies that we need to be looking at to actually get to the root of the problem,” she says, which is “why are folks in the position that they would need this in order to survive?”

Yang is still a longshot to be president, polling well behind the Democratic frontrunners. But his campaign feels like a glimpse of the future if Musk and Zuckerberg get their way: a shrinking government, powerful tech monopolies, and a thousand dollars a month to stave off a revolution.

Top image credit: Mother Jones illustration; Joshua Lott/Getty; Jae C. Hong/AP; Caroline Brehman/AP