Mother Jones illustration; Getty; Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas

Sixty-six years ago, Marion Ford, an ambitious Houston teenager who had been set to become one of the first African American undergraduates at the University of Texas, received a terse letter returning his $20 deposit to room in an all-Black dormitory because his admission had been rescinded.

The transgression committed by Marion Ford, a saxophonist, writer, academic standout, star athlete, and all-around striver? He told a reporter he wanted to try out for the all-white Texas Longhorns football team.

The Ford episode in 1954 unspools over a series of documents, many of them marked confidential, resting deep within the University of Texas archives. I came across these documents while working on a book about football and race in Texas. Among other things they illuminate how far the university’s regents were willing to go to keep their beloved football team free of Black players. That previous May, the US Supreme Court had handed down its Brown v. Board decision, and the regents, each appointed by a segregationist governor, were determined to interpret the ruling in the narrowest way possible. The Ford crisis—it was nothing less than that to the men controlling the university—was one of the first tests following the Brown decision of how a state university would fold in newly admitted Black students. Within weeks the state’s most powerful figures had convened to thwart the mere prospect of a Black teenager setting foot on the field.

There’s a larger story to be found in these and other confidential documents. More than a half-century later, they offer a glimpse of how American apartheid was maintained even after parts of it had been formally struck down—how, in particular, state and university bureaucracies were marshaled to serve segregationists’ ends. Methodically, insidiously, memo by banal memo, administrators constructed a two-tiered system at their university. To see the evidence of this up close, to hold these flimsy pieces of onionskin paper in your hands—carbon copies, filed away in folders marked “Negroes”—is to understand something essential about segregation. Jim Crow was office work, too.

Ford had been a top student at his all-Black high school when, in June 1954, he applied to the state’s flagship university. The Brown decision had been handed down in May and he was determined to capitalize on its promise. He was a go-getter: In his young life he had already worked as a newspaper carrier, a truck driver, a lifeguard, and a columnist for the school newspaper; known by the nickname Big Drip, he was a talented kid, well-liked and gregarious, keen to dance, a member of the engineering honor society.

In his application he said he wanted to major in chemistry. At first, UT officials put him off, suggesting he instead attend Texas Southern, a historically Black university. Ford thought he was getting the runaround, and he said as much—“Southern Discrimination” was the phrase he used in a letter back to UT’s dean of admissions, H.Y. McCown. “I am not interested in living in your dormitories or becoming socially prominent with the Caucasians,” Ford wrote, “but I do want a chance to get the best formal training in my state.” In a condescending letter of admittance in late July, McCown wrote back to Ford, “I hope that you will do well in the University and that you will get over your inferiority complex and the idea that you are being discriminated against.”

Finally, all appeared set for Ford and a half-dozen other young African American men to become the first class of Black undergraduates at the university. On August 16, the university sent him a room contract for San Jacinto Dormitory D, and Ford mailed in a $20 deposit. Around that time, he also submitted a rushee information card to UT’s Interfraternity Council, still on file in a warehouse of university records. He wrote that he planned to join the ROTC program, and in a sign of his eagerness, he asked that a copy of the fraternity handbook be sent to him.

But there was a problem: Ford, a brawny 5-foot-10-and-a-half, 209-pounder who had been a varsity swimmer and all-state lineman in high school, told a Houston reporter a week later that he hoped to play on UT’s football team.

The reporter, in turn, contacted UT regent Leroy Jeffers, a Houston attorney, to ask for comment. Jeffers said the regents hadn’t considered the prospect but that it would be weighed “from all angles for the best interest of the university.” Privately, Jeffers was alarmed. The following day, he sent a copy of the article—headlined “Houston Negro Seeks Grid Tryout at Texas”—to the members of the board of regents and the chancellor. It was one thing to admit African Americans, another to allow them to play on the football team—or really to let them represent the university in any capacity. On the very day, August 25, 1954, that Jeffers sent the article to the regents, Arno Nowotny, the widely beloved dean of student life at the university, wrote to UT President Logan Wilson about the problem of Black students who wanted to study at the university and also participate in the school band. “An undergraduate Negro student, J. L. Jewett, has inquired about playing in our Longhorn Band in the fall,” Nowotny wrote. “I hope we continue to admit Negro students only when we have to do so. I could wish that young Jewett had chosen the symphonic band or some other less spectacular student activity; but I plan to have a real conference with him, and stress the importance of his showing real humility in his band participation.”

Five days later, the regents chair, Tom Sealy, a Midland oil exec, went to the state attorney general with a question. This was John Ben Shepperd, who the following year would sue the NAACP in an attempt to disband it. Sealy wanted to know if the university was required “to permit such negro students upon admission to participate in such extracurricular activities as band and football or other intercollegiate activities.” That same day, the university’s dean of admissions wrote to the UT president that African Americans were taking “a more calculated approach” in their applications. There was some truth to this: The applicants, in league with civil rights activists, were quite reasonably trying to force the issue of their admittance—after all, the university, in defiance of the Brown decision, was still trying to push them to historically Black schools. After McCown told Ford that chemistry was offered at Texas Southern, for instance, Ford told him that he in fact wanted to study chemical engineering, a major not offered at Texas Southern. “They are now carefully advised and are constantly probing for programs of work not offered at one of the Negro institutions,” he wrote.

In a memo marked “personal and confidential,” Sealy informed the other regents that after a “full investigation,” the university had determined that Black students could take at least their first-year classes at Black institutions. In other words, even if Texas Southern did not have a chemical engineering major, it had first-year offerings that mirrored UT’s. The plan was essentially a delay tactic, meant to buy the University of Texas at least another year in which to figure out how to prevent Black students from enrolling.

And so, less than two weeks after Marion Ford had told the Houston Chronicle he wanted to try out for the football team, letters were sent to him and the other incoming African Americans, explaining that their admission had been rescinded. The university president, the regents, the university lawyers, and the state attorney general had huddled up and decided to bring down the full weight of the Texas government and its flagship university on this teenager and a half-dozen other African American admits for the crime of wanting to represent the school on the football field.

On September 3, Ford was refunded the $20 deposit for his room at a dormitory for Black students only, and he was informed by the university’s director for auxiliary and service activities that the rooming contract was “now voided.” “The Dean of Admissions at The University of Texas”—McCown—“has notified this office that your application for admission to the University as a student has been canceled,” said the letter, a copy of which was sent to the university president, confirming again that the university’s highest ranks were involved.

The sacrosanct football program remained unsullied, and some Texans who learned about the university administration’s about-face were pleased. J. L. Shanklin, a dentist in the Hill Country town of Kerrville, wrote McCown “to congratulate you on your very sane stand in re–the case of Marion G. Ford Jr.”: “The problem is not one of racial, religious, social, or political, but is one of our Constitutional rights…If Democracy is the best form of government and is to survive, we will have to fully subscribe to the theory that the majority must supersede the wants and claims of the minority. Surely the majority of Texans does not want to accept racial equality, nor do they want to foster a situation that will surely lead to social and sexual homogeneity.”

Judging by the clippings stored in the UT archives, there was little mention in the press of UT’s backtracking, apart from a one-sentence item in the Informer, a Houston Black newspaper. The story noted that Ford had been “rejected then accepted and rejected again,” a line that in its weariness suggests something of the condition of being Black in America.

Athletics, and football in particular, presented UT with a logistical conundrum: Even as it was resisting the integration of its student body, would the university ban other schools from bringing their Black athletes to UT’s fields and tracks? In 1956, the University of Southern California football team and its star running back, Cornelius Roberts, a Black man, were scheduled to play in Austin. UT officials deliberated over how to handle the prospect of Black fans showing up to the game. “One can visualize (with a shudder) the disturbance arising because a Negro attempted to sit next to or near a white person who had definite adverse feelings in such matters,” Lanier Cox, the assistant to the UT president, wrote to Sealy, still the regents chair, two and a half months before the game. Cox warned: “Since the University of Southern California has a star Negro fullback, it is entirely possible that his parents or friends from California may make the trip to Austin. It would be difficult to control the sale of tickets by visiting schools. Therefore, it would appear that little could be done other than to admit Negroes holding tickets in the visiting team section.” As for other Black people seeking to buy tickets, he said, “It is recommended that the Negro section in the stadium be continued and that all Negroes who ask for tickets be sold a seat only in this section. This should reduce substantially the possibility of Negroes sitting among the white spectators in the west stands and thereby creating a situation of possible ill feeling or even violence.”

In the end, Roberts, nicknamed the Chocolate Rocket, ran roughshod over the Longhorns, racking up 251 yards and three touchdowns. UT lost 44–20 en route to a 1–9 season. Among the spectators at that game was Marion Ford. He had played for Illinois before coming back to Austin as a transfer student, among the first Black undergrads admitted in 1956. Not long after the game, Ford approached UT head coach Ed Price to again float the idea of walking on as the university’s first Black football player. “Ed,” Ford said, according to Richard Pennington’s Breaking the Ice: The Racial Integration of Southwest Conference Football, “you need me. I can help you.” (“I was a cocky son of a bitch,” Ford later told Dwonna Goldstone for her excellent book Integrating the 40 Acres.) Price, who had not had a winning season in several years and who must have known he was likely to be fired at the end of the season, shrugged off Ford’s suggestion. “He was very amiable,” Ford, who eventually built a successful dental practice and remained a frequent face at Houston-area UT alumni events until his death in 2001, later told a reporter. “He knew he needed help. But he said, ‘It’s out of my hands.’ … It would have been a good stroke for Texas, a beautiful opportunity for a premier university to forge ahead and a hell of a rallying point.”

Maintaining segregation after Brown was hard bureaucratic work. It required technical clarifications, legal rationalizations, stalling tactics, even a new standardized testing regime to keep people like Marion Ford off campus. “The Brown decision was hardly self-executing at the University of Texas,” the legal historian Thomas D. Russell, who has written about how racial considerations shaped UT in the 20th century, has dryly noted. The logistics of apartheid led to occasional confusion. “For the second or third time now since 1955 my own department has had a bona fide and quite unsolicited application for a teaching assistantship from a Negro graduate student,” Leo Hughes, chair of the English department, wrote the university president on May 22, 1961. “On at least one previous occasion we rejected the application, in spite of a most impressive record.” The letter concluded: “What is the current administrative policy on the hiring of Negro teaching assistants?” Four days later came an answer: The university’s policy “is not to employ a Negro as an assistant teaching in the classroom but as an assistant assigned to a research project,” wrote president Joseph Smiley, a soft-spoken scholar of French from Dallas. “I think all of us concerned realized that this is an extremely delicate and complex problem.” Seven years after the Brown decision, the UT president deemed it okay for Black people to do lab work, behind closed doors, but not okay for Black people to oversee white undergrads.

The following March, Smiley got a note from the dean of students, who wanted him to weigh in on another evidently tricky issue: The Longhorn band had gotten inquiries from a Black high school in Dallas about its membership rules. One asked, simply: “Are Negroes eligible for membership in the Longhorn Band?” “It is my understanding that Negroes have previously been auditioned but have not been able to demonstrate the quality necessary for membership in the band,” the dean wrote to Smiley.

The machinery of segregation ran on patrician smarm, too. On July 20, 1961, Mo Olian, the undergraduate president of the Texas students association, told a Daily Texan reporter that the latest decision by the regents to resist integration was “narrow-minded, backward and hypocritical.”

Thornton Hardie, a West Texas attorney who was the bespectacled chair of the regents, was affronted. On August 2, he sent the undergraduate a page-long letter defending the regents as “gentlemen of the highest type” who had “given unselfishly of their time and talents toward the progress and well-being of the University.”

“I trust you have now recovered from your unfortunate loss of temper and that you regret your choice of language, which was highly insulting to these fine gentlemen,” Hardie wrote. “I hope you will now agree that an appropriate written apology to the members of the Board of Regents is in order, and that I am the one to whom such an apology should be address.” Olian declined to apologize. Athletics and dormitories remained segregated through the early 1960s.

In a note to other regents, Hardie suggested that as part of UT’s publicity campaign, it “should at least be mentioned” that Olian and David Lopez, the managing editor of the campus newspaper, “are certainly living examples of the lack of religious and social prejudice at The University.” Lopez is Hispanic; Olian, Jewish. (Olian would go on to have a successful real estate investment career in Austin. When I tracked him down and showed him the documents, he told me, “I’m still amazed how at that young age they tried to impugn my integrity.”)

One mid-October evening in 1961, three Black undergraduate women gathered in the lobby of Kinsolving, a white-only dormitory, despite warnings from the dorm matron, and went upstairs for half an hour to the rooms of some of their white friends before being forced to leave. The Black dorms were rickety, old, wood-frame buildings; Kinsolving was brick and stone.

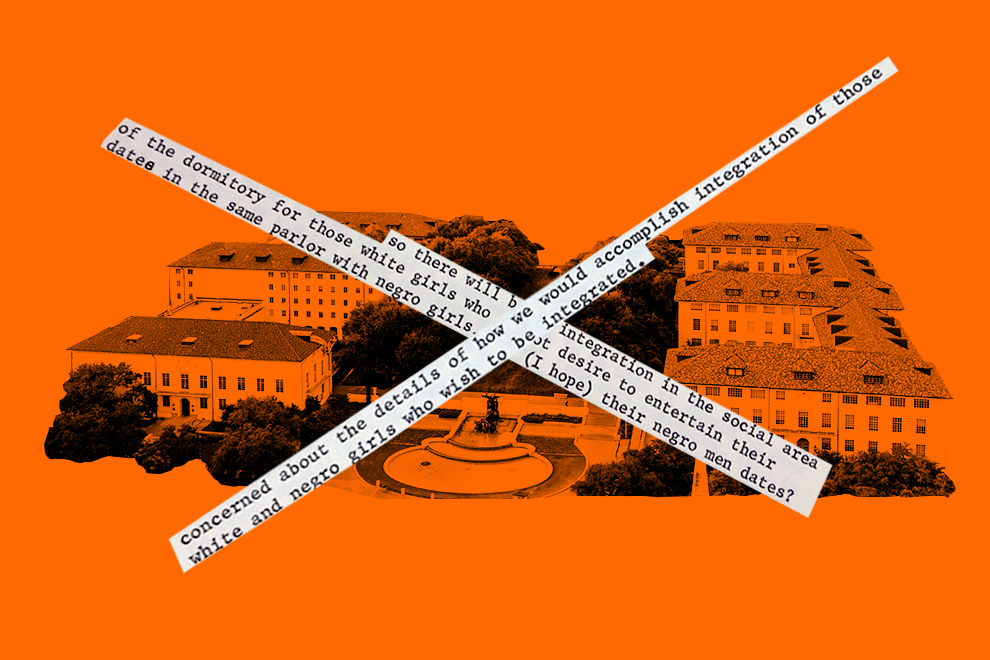

The regents were furious. In a letter to his fellow board members, a regent named W.W. Heath said the university should commission a survey of the parents of white girls whose dorms might be integrated. “They are paying the bills, have a more mature viewpoint [than students], and know best what is good for their own children. An appropriate poll question would be: ‘Do you favor complete integration of our girls dormitories, realizing this may require you (or your daughter) to room with colored girls, have your meals with them, and receive your dates in the same dormitory parlors with their dates, further realizing that any partial integration of such dormitories would merely be a step toward complete integration?’”

The tone came unhinged. Hardie now recommended that the university tell the parents of two white women who were involved in the sit-in “that if their daughters will promptly give the President of the University and the Manager in charge of Kinsolving a letter of apology, with a promise not to repeat the offense, they would be forgiven. Of course, it should be understood that the letters of apology would be subject to publication.” If they won’t apologize, he wrote, they should be made to leave the dorm within two weeks. “At the end of that time, if they had not left we should remove their belongings from their room and lock the door, and we should see that they were not allowed to reenter. It is quite true that they might file suit for damages, but we would have to take that risk.”

Many alumni were horrified at integration efforts. “I have had negroes around me all my life and still employ them in my office and in my home,” Waldo Pauls, scion of a Houston cotton merchant and a UT alumnus, wrote to the UT president shortly after the sit-in. “They are like children and if given an inch they will take a mile. If you treat them as your equal they will want to date the white girls and etc. and I mean etc.” Perhaps mindful of offending powerful donors, the university correspondence to racist alumni ranged from meek to obsequious. The UT president, Smiley, wrote Pauls that “all of us concerned feel that this is an extremely critical situation, and I assure you that we are doing our utmost to make the right decision.” In November 1961, an East Texas attorney and UT law graduate, Billy Hunt, also wrote Smiley about a complaint he had received from a wealthy, elderly client whom he had encouraged to leave at least $10,000 of his estate to the University of Texas. The client had learned that a University of Texas law professor had circulated a petition calling for the end of segregated facilities on campus:

Today, I was called upon by this gentleman to prepare another will which omitted this bequest. This was all brought about by the idiotic action of the faculty in general, and one of the professors of the law school, in particular, in pushing through some sort of resolution calling for the removal of segregation practices in regard to the restrooms in the dormitories. When the story appeared in the press, this client, who has rather strong feelings on the matter, came to my office and stated that he would leave no money to any institution which would harbor such people on its faculty. Frankly, I could not work up too much enthusiasm in trying to get him to change his mind.

Smiley, the UT president, wrote to Hunt to say his letter “obviously distresses me.” “It is clear, of course, that we cannot afford to sustain the loss of any potential private support, for, as you know, this kind of support is indispensable our goal of achieving high academic excellence,” Smiley said, explaining that the administration and board of regents “are doing our utmost to define and attain the wisest possible solution of these problems.”

Instead of backing down as the regents had demanded, the young women who’d participated in the sit-in chose to file suit. A UT law professor who served as their counselor was deemed a traitor by the regents. The sit-in became a cause: When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited the campus in March 1962 to give a talk on segregation—before an audience of 1,200 people on a campus that was less than 1 percent Black—he announced that “Old Man Segregation is on his deathbed. The only question is how expensive the South is going to make the funeral.” And in May a national chemical engineering conference to be hosted by UT was suddenly put in jeopardy because one of the member associations had complained. “Unfortunately there appears to be real danger that we will lose the conference if we do not act soon to correct a minor technicality in our dormitory regulations,” an engineering dean wrote to Smiley, the university president. The “minor technicality” was that the dorms were segregated by race—and one of the participating engineering societies from elsewhere in the country had raised an objection.

The segregation of the dorms had practical, nearly farcical consequences. A small note to the university president in the summer of 1962, at a time when white and Black housing remained segregated, reports that a pair of Black kids in Austin for a high school band conference at UT had found that their rooms lacked air conditioning. In mid-June, at the time of this conference, Austin broils. “Literature about the conference mentioned air-conditioned quarters,” says the index card note. “Presumably Nelson Patrick, who is in charge, had checked and all the students attending were supposed to be white.”

Facing pressure from the dorm integration lawsuit, UT Chancellor Harry Ransom told the student-plaintiffs to withdraw the suit in the spring of 1964, a few months before President Lyndon Johnson was due to give the university commencement address. Keen to end a legal showdown they were likely to lose and concerned about their relationship with Washington, university officials pledged to “voluntarily” integrate the dorms on their own.

“That was part of the reason why the University wanted to integrate as fast as possible,” one of the plaintiffs, Sherryl Griffin, told the Daily Texan in 2016. “So that when the President of the United States came, the University would not still be involved in the punitive legacy of our lawsuit.”

UT also faced the real possibility, with the impending passage of the Civil Rights Act that year, that it would have to forfeit federal funding if it remained, on paper, segregated. Heath, an East Texas attorney who was an old friend of Johnson’s and now chaired the board of regents, admitted that he “came on the board with a lot of prejudices” and did not realize that “on federal research grants, you get cut off a lot of places if you’re not integrated.” The president, in other words, forced his hand. At its meeting on May 16, 1964, the board of regents ordered the full integration of the university. According to the self-congratulatory official minutes of the meeting, “the Board completed its task of ‘integration with all deliberate speed’ as promised, and without troops, marshals, violence or bloodshed.”

Today the University of Texas has sought to repair the historic wrongs. It has an Office for Inclusion and Equity, hosts an annual conference focused on issues facing Black student-athletes, and welcomes pioneering African American admits back for an annual reunion, and even finds itself under attack in the courts for its affirmative action policies. “For half of UT’s 135 years, the university did not admit African American students,” university president Gregory Fenves said in a 2018 speech. “Our history of exclusion and segregation gives us a responsibility to stand as champions of the educational benefits of diversity.”

The history of segregation at UT, as at other Southern universities, is not so ancient. On a beautiful mid-October evening in Austin, at halftime of a game against Kansas, members of the 1969 national championship football team gathered at midfield and held aloft their Hook ‘Em Horns hand signs. Marking the 50th anniversary of that Longhorn campaign, the band struck up “The Eyes of Texas,” and the crowd of more than 97,000 fans took to their feet in burnt-orange salute. It was a poignant moment: Here were aging athletes being regaled once more for their boyhood feats. But there was little or no official reckoning with a singular fact: that this group was the last all-white team to win the national championship. The first Black player didn’t make the varsity team until 1970—at least a half-dozen years after the regents had decided, on paper, to fully integrate the university and 16 years after Marion Ford had announced his desire to play ball.

Asher Price is a staff reporter at the Austin American-Statesman. His new book is Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact, from which part of this article is adapted.