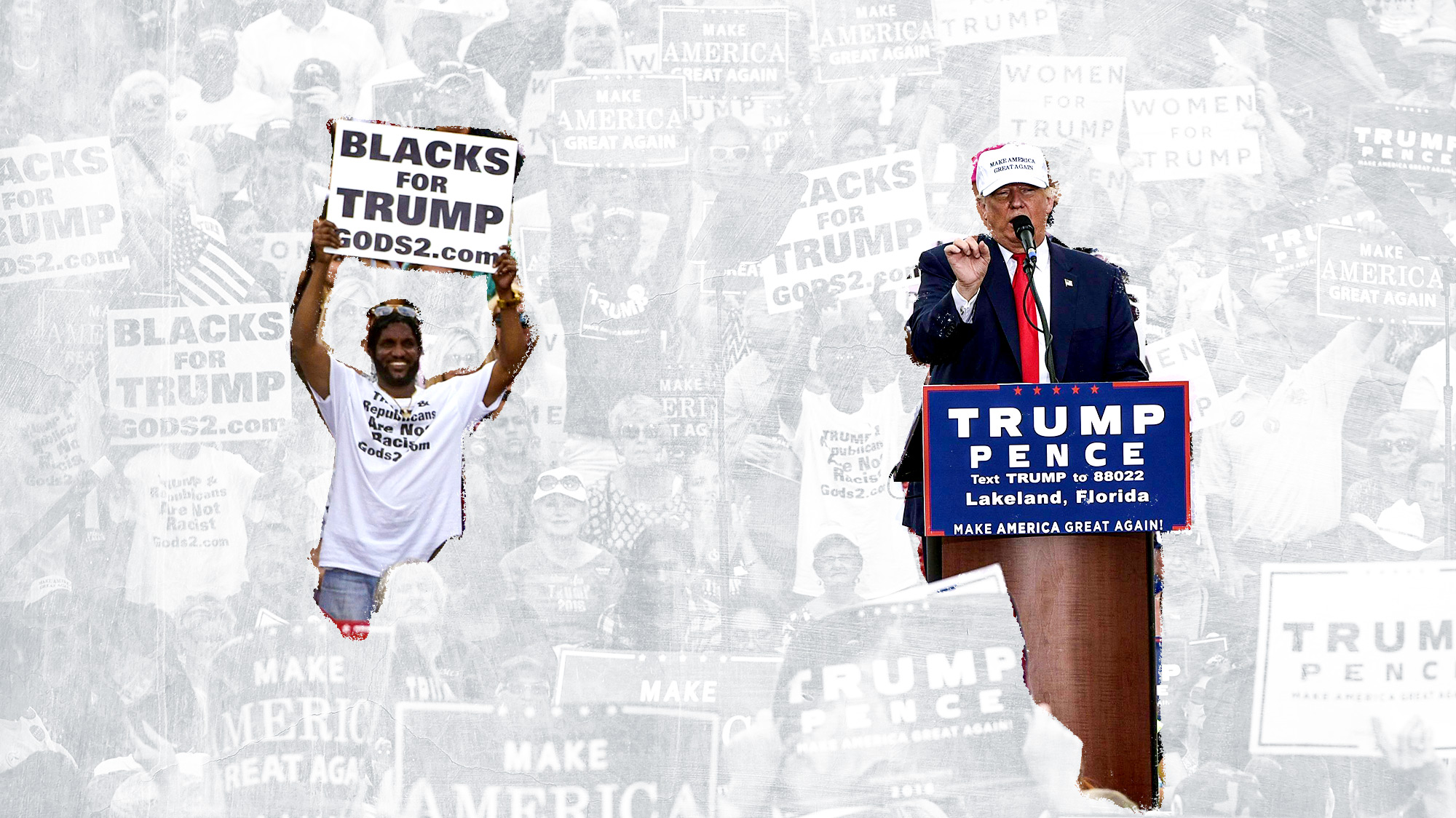

Before Kanye West posted photos of his MAGA hat, and before anyone had ever heard of the video bloggers Diamond and Silk, there was Michael the Black Man. If you’ve ever watched a Donald Trump rally, you’ve almost certainly seen Michael, standing as close as he can get to the president, waving his BLACKS FOR TRUMP sign, wearing a white T-shirt that proclaims with promiscuous capitalization: “TRUMP & Republicans Are Not Racist.” He became such a consistent ponytailed presence at Trump events—by his own count he’s been to more than 70 in the last four years—that Kenan Thompson once played him in a Saturday Night Live sketch. (Thompson’s version of Michael held signs reading “BLACKS FOR WHITES” and “CASH 4 GOLD.”)

He’s gone by the names Maurice Woodside, Michael Symonette, and Mikael Israel, but now he prefers to be called Michael the Black Man. He’s a peculiar character on the fringe of American politics, a part-time musician and club promoter who hosts a radio show on his own pirate station in Miami. He also has several websites promoting various religious and political conspiracy theories, and he’s friendly with Republican leaders across South Florida. A video on his site shows Florida Sen. Rick Scott, back when he was still governor, telling Michael, “I saw you on TV with Trump. You did a good job.” Michael also has pictures of himself with Sen. Marco Rubio and former Florida Rep. Allen West.

The president has singled him out at rallies to thank him. At a 2016 campaign event in Miami, Trump pointed to Michael from the stage. “I love that sign,” he said into the microphone. “‘Blacks for Trump,’ I love that sign. Thank you!” At another campaign event, in Lakeland, Florida, Trump held up one of Michael’s signs, waved it, then kissed it.

Over the years, several reporters have taken notice and published stories examining Michael’s past, including his jarring criminal history, but I wanted to know more about this person, someone openly embraced by a Republican Party that’s practically anathema to African Americans. (In most polls, Trump’s approval rating among Black people is somewhere between 12 and 20 percent, with a vast majority consistently disapproving.) How did he become the “Blacks for Trump” guy? What’s it like being one of the only Black faces in a sea of white at those rallies? After all, as the election cycle gears up, we’re going to be seeing a lot more of Michael the Black Man.

So I reached out to him through a number listed on one of his websites. After a couple short conversations on the phone, he invited me to come down to Miami to interview him at home. We ended up discussing everything from how he became a Republican to where his money comes from to the time in the ’80s and ’90s when he was in a murderous Black supremacist cult and went on trial for allegedly stabbing a man in the eye with a stick and beating another man who was later decapitated.

When we met, Michael was living in an expansive, ’80s-chic mansion in a posh Miami neighborhood not far from the beach. The house was surrounded by palm trees and a tall white wall with a security gate. There was a dock on the canal out back. From a distance it looked like an immaculate property—the county estimated the value at $1.4 million—but as I got closer I realized the entire building was waterlogged: warped plaster and rust-colored stains on the outside walls, red tiles missing from the roof, crumbling paint, massive cracks in the driveway cement. On the day of my visit, there was a Rolls-Royce parked out front but no working air conditioning inside. (I would later learn that the house was in foreclosure.)

In the living room, he had elegant, worn leather furniture, a fish tank half filled with foggy water, a piano, and an entertainment center with a muted TV turned to Fox News. When I showed up, Michael told his associates to start recording me. Two men stood in front of the couch, one holding a video camera, the other holding a phone. Three other guys, all of them older Black men, sat in chairs nearby, watching and nodding along as Michael spoke. He never told me who they were, and they never introduced themselves. Once in a while they clapped or muttered affirmatives like you might hear during a church sermon or a political speech. Soon the man holding the phone got tired and sat down.

And with good reason. What I’d originally planned as a short visit quickly turned into one of the most surreal conversations I’ve ever had. Michael is frenetic when he talks, going on for long stretches without pausing, skipping from topic to topic—within the span of a minute he might quote Trump, curse Hillary Clinton, and reference the Book of Ezekiel.

To start, Michael wanted me to know that, no, Donald Trump doesn’t pay him to come to rallies. And, no, nobody asks him to stand onstage behind the president, right in frame for the camera. Sitting on the old leather couch in his warm, muggy living room, Michael told me that he gets in line early, sometimes a day in advance, and then spends all night waiting. And he said there are often dozens of other Black people at those Trump events, “but they stay on the edges because they don’t wanna be seen.”

Michael likes to be seen, and he likes to share his views on politics and religion: a blend of Fox News talking points and idiosyncratic Old Testament interpretations. He also likes to share his personal story. He grew up in Miami in the ’60s at a time of strife and transformation, when the civil rights movement and an influx of immigrants set the backdrop for a number of racial uprisings. His father was a Republican, Michael said, because GOP politicians would come to the nightclub he owned. “He used to brag on Nixon, and he loved Reagan,” Michael told me. “You know you can’t argue with your dad.”

In the late ’70s, Michael saw the miniseries Roots. He remembers the image of LeVar Burton in shackles, the scenes of Black people being whipped. He says this was what led him to hate all white people.

It was around that time, he told me, that he briefly became a Muslim, but he abandoned the faith after he met a man named Moses Israel. “He gave me a flyer,” Michael told me, “and said, ‘The white man is the devil!’” Born Hulon Mitchell Jr., in Oklahoma, the same man would later call himself Yahweh Ben Yahweh—Hebrew for “God, son of God”—and start what prosecutors alleged was a violent, race-based religious sect that firebombed perceived detractors, mutilated defectors, and allegedly murdered as many as 14 people in the 1980s.

Soon, Michael joined Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s church, the Temple of Love, located in the Liberty City section of Miami. Founded in 1979 as a branch of the Black Hebrew Israelites, the church preached a message of Black supremacy, tied up with the idea that all of humanity descends from the ancient tribes of Israel and that those tribal battles still exist throughout the world. The Temple of Love was initially seen as a positive force in a deteriorating part of the city. The neighborhood was once home to a thriving Black middle class that had fled to the suburbs amid an influx of displaced lower-income Black residents from nearby Overtown, which had been ravaged by “urban renewal.” The Liberty City of the late 1960s was characterized by racist neglect and police violence. These were the conditions that gave rise to the Temple of Love. Like a lot of Black and Black-oriented cults, Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s outfit set up shop in the large gaps in public provision. (He is said to have patterned himself in part after Father Divine, the Black spiritual leader whose Peace Mission Movement served material needs that were going unmet in Jim Crow America—“extensions,” for instance, that were essentially safe, affordable hotels.) The group bought up property in blighted areas and pushed “for better education, employment opportunities, housing, and health care for African Americans,” as Julius H. Bailey points out in his history of African American religion, Down in the Valley. Police appreciated that the Temple of Love seemed to clean up the crime-ridden streets of some of Miami’s most dangerous neighborhoods. Politicians stopped by, seeking the Yahweh vote.

After a few years, for reasons that are still unclear, Yahweh Ben Yahweh changed what he was saying about race. “One day he told me, ‘Son, you know all white people are not the devil,’” Michael remembered. He acted out the conversation that followed, flailing his arms. “I was very upset, but Yahweh Ben Yahweh said, ‘Son, if you have a race war, you’re going to have to kill me.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘Son, I’m lighter than most white men,’ which was true.”

Michael was encouraged to make amends with the white friends he’d forsaken. That was going to be hard enough, but then, he said, “Yahweh Ben Yahweh hit me with the ultimate bomb: ‘You know you should never vote for Democrats.’”

They argued at first. Abraham Lincoln, Yahweh Ben Yahweh told him, was a Republican. Michael looked it up and returned the next day, “flabbergasted.” The way Michael recounted it, Yahweh Ben Yahweh told him, “The Democrats were the slave masters, and they were the murderers of our people.”

Everyone at the temple was told to register to vote—and to support the candidates their leader liked. Michael had an up-close view as Temple of Love followers helped get a few underdog Republicans elected to various local offices. He watched as Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s influence and power grew. By the mid-1980s, the FBI estimated that there were about 5,000 members spread over 38 different cities. At one point, Yahweh Ben Yahweh and the group controlled $100 million in real estate assets, according to the Miami Herald. A few years later, the mayor of Miami declared October 7, 1990, “Yahweh Ben Yahweh Day.” The Southern Poverty Law Center would later call that moment the culmination of an “orgy of misplaced praise.”

While the sect preached peace and rebuilt homes, the public started hearing stories about severed ears and public beatings of dissidents. In 1994, Sydney P. Freedberg, a reporter for the Miami Herald, wrote a book about the group. Brother Love: Murder, Money, and a Messiah chronicles the leader’s rise to power, the lifestyle inside the Temple, and the investigations that linked the group to extortion schemes, fire bombings, and more than a dozen murders. (Interestingly, at one point, in an aside, the book also compares the cult leader to Donald Trump, noting that they both tended to acquire property with borrowed money.)

Members of the sect adopted new names and wore white robes with white headscarves everywhere they went. A security team roamed the halls of the Miami temple, and some of the surrounding streets, with wooden shepherd sticks they called “staffs of life.” Some of the followers were reportedly seen walking around with machetes on their hips. Dissidents lived in fear. One former member was found dead and dismembered at the edge of the Everglades. Another member told police he killed six people at the behest of Yahweh Ben Yahweh.

Michael makes a brief appearance in Brother Love. Freedberg describes him as “a Romeo-like jazz singer whose voice was a blend of Nat King Cole and Johnny Mathis.” When the FBI eventually arrested Yahweh Ben Yahweh and his followers in 1990, Michael was charged with two counts of conspiracy to commit murder and spent months in jail awaiting trial.

Michael’s brother, Ricardo, who was also a member of the Temple of Love, testified against him in court, saying that Michael stabbed a man through the eye with a sharpened stick and that he participated in the beating of the man who ended up headless in the Everglades. Michael testified in his own defense. According to Freedberg, he was “so hyperkinetic that courtroom spectators couldn’t quit chuckling. He quoted love scriptures as if reciting from a mail-order catalog.” He reportedly sang a song to jurors and told them, “I am like a sheep, that’s what I am. I’m not a warrior.”

After a prolonged trial, the group’s leader was convicted in 1992 on 14 charges of murder conspiracy and spent 11 years in prison. He died of prostate cancer in 2007. Michael and a handful of other followers, though, were found not guilty. Later, Richard Scruggs, one of the prosecutors in the case, told the Miami New Times that the verdict in Michael’s case was “an acquittal by pity.”

When I asked Michael about it, he said Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s convictions were purely political, stressing that the group was not convicted of the underlying murder charges. “If they didn’t do any of the acts,” he asked me, “then what the hell was the conspiracy?”

He told me the eye-stabbing “never happened” and that the victim was seen with his eye weeks after the alleged murder. “All of it was stupid.” (The victim is presumed dead, and his body has never been found.) He said the other murder charge—he referred to it as “this so-called act”—only came up when prosecutors couldn’t get him for money laundering. He told me that, yes, at least one of Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s followers was a murderer: a former NFL player named Robert Rozier. Rozier told police that Yahweh Ben Yahweh ordered him to kill white people chosen at random and Black people who’d insulted the leader. Michael told me all of those murders—Rozier confessed in court to seven—occurred before Rozier had joined the temple. (Yahweh Ben Yahweh also publicly excommunicated Rozier before his trial.)

As we talked, Michael spent several minutes acting out various scenes from the trial, sometimes standing up and waving his arms, sometimes calling over to the men watching us, sometimes slapping me on the shoulder. At one point he leaned over and spoke directly into my recorder to compliment Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s former attorney, Alcee Hastings.

“I don’t really like Alcee, because you’re a Democrat,” he said. “But I’m gonna give you your props on this one.”

After Yahweh Ben Yahweh went to prison, Michael continued to involve himself in politics. In South Florida, reporters are used to his bizarre claims and antics. He showed up to a rally for then-candidate Barack Obama in September 2008 with signs reading “Obama Endorsed by the KKK” and “Blacks Against Obama.”

I asked him how he came to support Donald Trump. Michael told me he actually encountered Trump years earlier, in New York.

“A long time ago me and Yahweh Ben Yahweh was marching down Broadway, and Yahweh Ben Yahweh stopped and had a little chat with Trump,” he told me. “I didn’t listen to what he was talking about. Then Yahweh Ben Yahweh came back and said, ‘See, son. Now, that’s the kind of white man we need as our president.’”

He was evasive, though, when we started talking about how he could afford to travel to so many Trump events across the country. Who picked up the tab on flights to Arizona, Texas, South Carolina? He first told me he and his friends all used to buy and sell houses, that they were rich when George W. Bush was president. “We were just making money hand over foot,” he explained. “It was just easy because the regulations were not there.”

When I pushed the issue, he admitted sometimes the local Tea Party pays for some of his travel. “We go out there and just stand there. Just being Black is an amazing phenomenon.” (When I reached out to Tea Party members in the Miami area, most didn’t return my calls.)

That’s how he’s had the chance to meet Marco Rubio, Rick Scott, Allen West, and Jeb Bush. He went to a big Glenn Beck rally in Washington, DC, and, he told me, Andrew Breitbart used to ask him about the Bible.

Given his extreme views and his occasional proximity to powerful politicians, I asked him if he’s ever been interviewed by the Secret Service.

“I had been questioned by them one time,” he told me. “But they just wanted to make sure everything was okay, which is cool.” Now, he said, the agents are used to seeing him and ask how he’s doing. He said some have even told him that they listen to his radio station every day.

“They know who I am, what I’m thinking.”

A representative from the Secret Service politely told me the agency had no comment for this story.

Michael told me he doesn’t drink or smoke, but he does sometimes host parties where drinking and smoking happen. Some of those parties, he noted, have resulted in noise complaints. He’s also been arrested at least five times since his murder trial, on charges ranging from grand theft auto to attempting to carry a gun onto a plane, but he was never convicted. Michael said that each incident was a misunderstanding or a mistake by officers.

In 2010, police came to the house after Michael’s adult son, Jeremiah, fired an AK-47 out by the canal, the Miami New Times reported. Officers said the shots were an attempt to intimidate swimmers who had climbed on to their boat, and Jeremiah was charged with aggravated assault. Michael told me his son was shooting in the air to scare away men trying to steal his boat.

The topic of his yacht came up in discussion a few times throughout the afternoon, actually. It was a four-story party boat he sometimes used to help raise money for Republican politicians. The boat’s name: “Boss.” From our conversation, it’s not clear at all what happened to it. At one point, Michael casually tells me that local Democrats sank the yacht. At another point he said it was the City of North Miami, and that he plans to sue. Whatever happened, the loss seems to have devastated him.

“When they took my yacht,” he told me, “I’m not gonna lie, that broke me.”

His monologue stretched across the afternoon. At one point, the battery in the video camera that was trained on me died, and there was some discussion about whether there was a backup battery—and if so, where it might be.

The conversation drifted back to Trump, and I asked what he thinks of the president’s policies. That started him on a diatribe about how “nine guys in the Republican Senate are actually Mormons” and how “Mormons are mostly Cherokee.” (He also believes that the KKK is made up entirely of Cherokees.)

If you go to the websites he advertises on his signs and T-shirts (BlacksForTrump2020.com and Gods2.com), you’ll be redirected to HonestFact.com. It’s an early-internet-looking site, a mishmash of photos and video links and texts of various fonts, sizes, and colors. Michael’s posts touch upon everything from how Hillary Clinton wants to start a race war and sides with ISIS to why Judge Roy Moore is innocent of any allegations of sexual misconduct with minors. The site is also filled with references to Canaanites and Cherokees, like his strange claim that “PROTESTERS are PHONEY Black people & are really East Indians & Cherokees acting Black.”

When I asked him about these things, he explained that he believes that all of the races in the world can be traced back to Noah’s sons, one of whom was evil. Most white people, he said, along with Latinos, Asians, and Black people in America—but not Africa—have descended from Noah’s good sons. The descendants of Ham are the evil ones, the ones he called Canaanites and Cherokees. He cited scripture so fast it was impossible to keep up.

Michael had made it clear that his entire worldview—including his support for President Trump—had been shaped by his time with Yahweh Ben Yahweh. The longer we talked about his beliefs and their origins in this strange cult, the more I wondered if Yahweh Ben Yahweh’s temple has, despite the murder trials and prison sentences, returned to South Florida. After nearly three hours of bizarre conversation surrounded by strangers in a humid living room, I was uncomfortable, and I started trying to wind down the conversation. Before I parted for the day, I asked him: “Is Yahweh Ben Yahweh back?”

I don’t know what I expected to hear, but Michael just looked at me and shook his head.

“The group never left,” he said. “I’ve always been Yahweh.”

Michael walked me to the door, out past the Rolls-Royce, and through the security gate. We shook hands and, with the same smile he wore all day, he told me to look for him and his sign on TV at the next Trump rally.