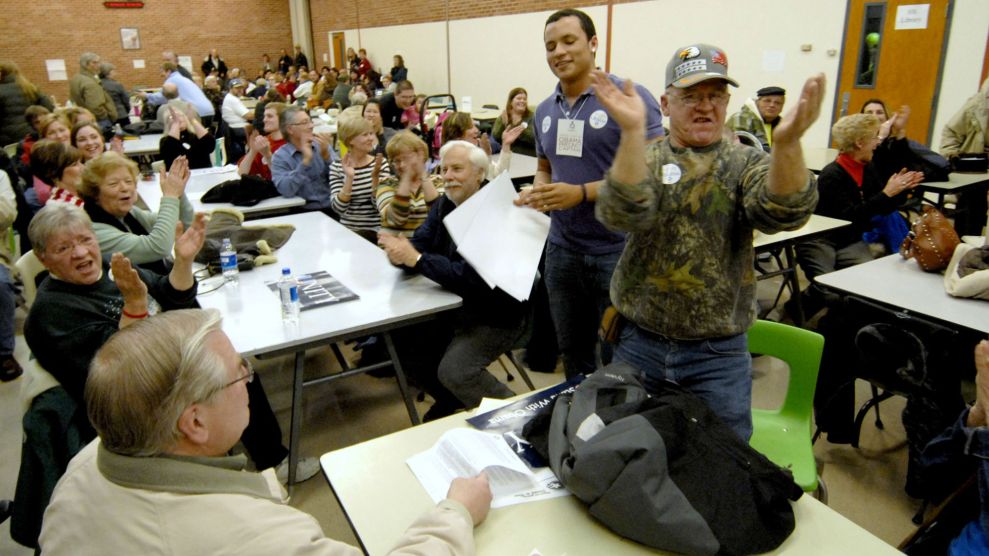

Caucus participants in La Mars, Iowa cheer for Barack Obama in 2008.Dave Weaver/AP

A dozen years ago, I set up shop at a Des Moines middle school to cover the Iowa caucuses on a snowy January night. In a process that has since remained unchanged at heart, participants filed in and divided by neighborhoods between a classroom, the library, and the gym. In each space, they then gathered into clusters in support of their candidate—the big ones in 2008 being Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and some guy named John Edwards.

Speeches were made and buttons were donned. After seeing the size of preliminary huddles, under the prying eyes of their neighbors, some people—whether from the warmness of their heart or the pressure of their peers—moved to pad out a group who otherwise would fall short of the 15 percent viability threshold needed to remain in the contest. Delegates selected that night would work through a months-long ladder of party gatherings, with a handful being sent to the Democratic National Convention in August to formally select a presidential nominee.

But before that could happen, headcounts needed to be made and math be done. Eliminated candidates’ supporters moved around again, as campaigns’ designated caucus captains and self-selected extroverts tried to woo them to join the remaining contenders. Among the books, Edwards supporters offered snacks. On the basketball court, pro-Obama chants broke out as talliers repeatedly asked scores of caucus goers packing the bleachers and standing in the backcourt to please, please, please stay still so they could get accurate numbers. People with other obligations—maybe the night shift, maybe a new baby, maybe their own bedtime—filtered out, effectively disenfranchised as counting went well past an hour.

Back home the next week, friends asked for a debrief. I told them it reminded me of something I’d recently seen on YouTube: grindadráp, a centuries-old community organized whale hunt practiced annually in the Faroe Islands, when the animals are driven out of the North Atlantic into shallow bays and then beached and bludgeoned with clubs, or stabbed with gaffs until the water runs red. Both events were dynamic, homespun, an exercise of tradition, a visual spectacle—yet archaic and totally disturbing. How do these things happen in the 21st century? Could what I witnessed in Des Moines really be the best way to kick off the selection of the next Leader of the Free World?

This week, I spoke with Josh Putnam—an academic whose PhD research focused on the parties’ quadrennial convention delegate selection processes, and who runs FrontloadingHQ, a blog that has exhaustively chronicled the subject—to ask if time is catching up to Iowa’s process or its place at the head of the line.

Both have long been questioned. Before Julián Castro left the race, he decried the sorry situation of putting Iowa and New Hampshire in a position to winnow the field and create momentum defining victories when states with more diverse demographics would likely make different choices. “There is a reason that Nevada and South Carolina were added to the lineup of early states in the 2008 cycle and have been there ever since,” says Putnam. “But it remains the fact that you have these overwhelmingly white states that are going first.”

That night in 2008, Hillary Clinton lost to both Edwards and Obama, setting off a decade-long chain of events, spurred by Clinton’s dislike of the contests, that has made caucuses something of an endangered species. On Friday, a podcast was released where she turned up the heat, flatly calling Iowa’s system “undemocratic.” She’s not wrong.

Putting aside racial demographics, the way Iowa Democrats caucus is destined to disenfranchise. They kick off at 7 p.m., and wrap up on their own schedule—if you can’t make it then, or if you can’t stick it out to the end, you’re mostly out of luck. Absentee voting isn’t an option for Iowans out of state for work or school. If you have a mobility related disability or anxiety about crowds, the process of shuffling around sometimes packed and rowdy rooms creates unique barriers. Like the Electoral College, the party’s rules can advantage rural areas. One recent analysis showed that it only takes 43 participants in tiny Fremont County to win a delegate from a caucus, but in Johnson and Story counties, which both host state universities, it takes more than 200. In Polk, home to Des Moines and the state’s largest county, the number is about 150.

Iowa’s caucuses are a relic of the age where a smaller group of Democratic heavies had more sway over the selection of the nominee. In the big cities, think ward bosses and power brokers. In Iowa, a few dozen die-hard party activists would gather in precincts to select their delegates to county conventions, who in turn would select delegates based on region or congressional district, who in turn would select state delegates. (It all takes awhile, so they have to start early in the year.) In fact, Iowa Democrats go through the same precinct-on-up process every two years before holding their state convention, where they tinker with their platform, endorse local candidates, and conduct other party business. Most of the time, away from the glare of the national media, the first caucus night in the dead of winter is a modestly attended affair. But when there’s a presidential race, participation booms. In 2016, when Bernie Sanders and Clinton faced off, the busiest caucus site saw 900 people turn out, and took hours to count.

That year, Sanders, with his energized and activist base, performed well in caucus states across the country, providing a ballast of delegates that allowed him to nip at Clinton’s heels through the last primary contest. After the convention, representatives of their campaigns began meeting under a party “Unity and Reform Commission,” where Clinton, as the nominee, had the upper hand. “The fact that caucuses are lower turnout affairs and disenfranchise some voters more so than others was seen as a problem in her camp, going back to 2008 and to a lesser extent in 2016,” Putnam says. Clinton’s allies used their power to urge local parties to switch to primaries, and to encourage states sticking with caucuses to draft plans that would broaden participation.

Since then, Democrats in Washington, Idaho, and Nebraska have abandoned party run caucuses, instead opting to select their presidential convention delegates in state run primaries that accommodate a vastly greater number of voters through a largely intuitive process. In Hawaii and Alaska, they ditched caucuses for party run primaries. According to Putnam, such changes have left Iowa, Nevada, and Wyoming as the only states still caucusing in 2020.

“There’s kind of a disconnect,” Putnam says, explaining Democrats’ evolving opinion on caucuses. “’Here we are as a party talking about how everyone should have the right to vote, and the ability to vote, and we should increase participation. But we’ve got these institutions, these caucuses, where we see low turnout. So we need to square that to some degree.’ Most state parties took that very seriously.”

Iowa, too, heeded the call—in its own small way. The state party website boasts of its changes, promising they’ll make this year “the most accessible, transparent, and successful caucuses ever.” But compared to switching to a primary, the tweaks are extremely modest. And the new rules end up providing evidence of how Iowa’s system still flies in the face of basic notions of democratic fairness.

The clearest boost to transparency will be the release of three official sets of numbers: Not just, as the state party has always made available, the smaller number of how many local delegates each candidate won on caucus night, but also much larger headcounts of caucus-going Iowans’ first and final choices. This could create the impression of two, or even three, separate winners on caucus night, triggering a debate about who really “won.” (The caucus determines fewer than 1 percent of the pledged delegates who will select the presidential candidate; winning Iowa, however defined, has always been more a show of force than a practical step to the nomination.) A disconnect where one or both headcount numbers show a candidate with more supporters turning out on caucus night but emerging with fewer delegates would only highlight how the contest’s intricacies can work against the principle of one person, one vote.

To increase accessibility and participation in 2020, Iowa initially proposed creating a “virtual caucus,” a phone-in system that would have allowed the state’s registered Democrats to key in a PIN number and select a candidate. But after nearly a year of planning, the DNC rejected the idea in August, citing security issues. “After Russian interference in the 2016 election, there just wasn’t a level of comfort there to allow Iowa to move forward with that,” Putnam says.

Instead, Iowa’s party expanded a tiny 2016 pilot program creating “satellite” caucus locations, where people who can’t make it to their normal caucus can participate. Most of the 87 locations are in Iowa, and aim to give a bit of flexibility to people who can’t attend a caucus at 7 p.m., or to nursing or retirement home residents. But the ones that aren’t in the state illustrate how the nice-sounding goal of expanding participation can easily create new forms of unequal access. Iowans living out of state volunteered to create and host the events; about a third are in places in Arizona, California, and Florida—communities popular with snowbirds, including a country club house, a resort, and a beachfront condo building. Three will take place in buildings affiliated with Ivy League universities. There’s one in Glasgow, and one in Tbilisi, Georgia—yes, a that’s a satellite caucus in a former Soviet satellite in the Caucasus—but none in Mexico City, London, or anywhere in Africa, Asia, or South America.

Given its shortcomings, how likely is it that the Iowa caucus still exists and lies at the start of the process next time Democrats select a nominee? According to Putnam, pretty likely. Any movement to pressure Iowa to switch to a primary would need to account for a New Hampshire law requiring state officials to schedule their primary so it remains the nation’s first. And adjusting the order of the early states would almost certainly require the cooperation of both national parties—and “what do the parties agree on these days,” Putnam noted with a laugh. “There’s got to be political will to do this—not only to do this, but to have an alternative. And I don’t get the sense there is a distinct alternative that will appeal to enough people.”

For more than a year, the Democratic presidential contenders have crisscrossed Iowa warning about the supreme importance of defeating President Donald Trump, of removing a president who was elected without majority support, who has denigrated people of color, who has worked to suppress votes, and who has attacked the country’s democratic institutions. When dust settles after 2020, perhaps the party’s leaders should spare a moment to think about those issues, alongside what happened in Iowa on Monday night.