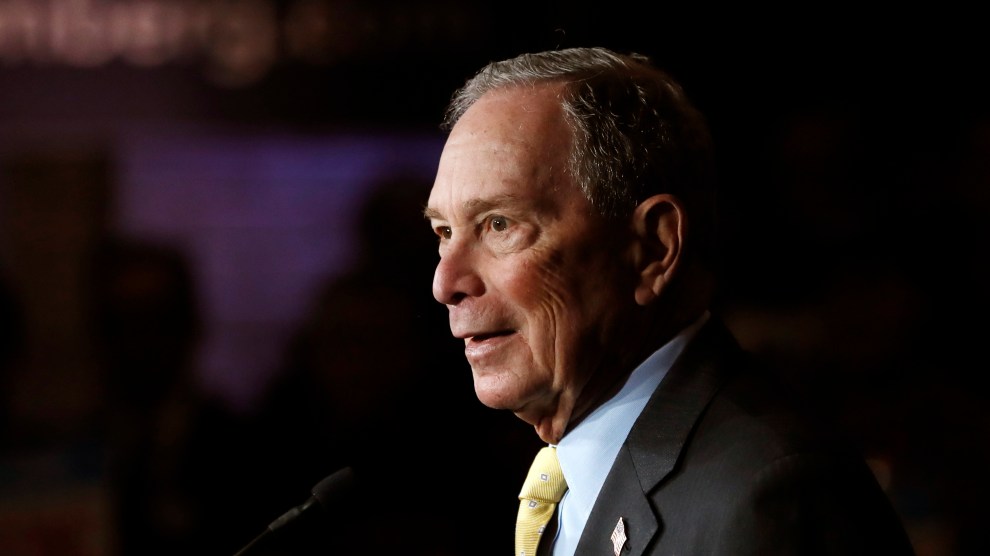

Former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg at the Democratic presidential primary debate Wednesday, Feb. 19, 2020, in Las Vegas, Nevada.John Locher/Associated Press

Michael Bloomberg’s campaign for president has been an attempt to reinvent the presidential primary process entirely. The billionaire and former three-term mayor of New York City jumped into a race that was already well underway, skipped the first two contests (and the third, and the fourth), and hatched a scheme to emerge on Super Tuesday as the party’s last best hope to defeat Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.

It was a neat little trick. Because he didn’t have small-dollar donors, he couldn’t participate in any of the debates, and because he didn’t participate in any of the debates, he existed on an entirely different plane from everyone else, above and beyond the Midwestern passive aggression and canned zingers and the same three questions about Medicare for All asked 27 different ways. And it’s been working! In a few short months, Bloomberg picked up the endorsement of seemingly every mayor of a midsize American city, spent more than $350 million on ads and campaign staff, tried to shake a dog’s mouth, started a Weird Twitter account, and got a lot of people’s hairdressers and their friends to think that Barack Obama had endorsed him. (Spoiler: He hasn’t.) Oh, and at some point along the way, Michael was shortened to just “Mike.”

You can cut the line, it turns out, but sooner or later the line catches up with you.

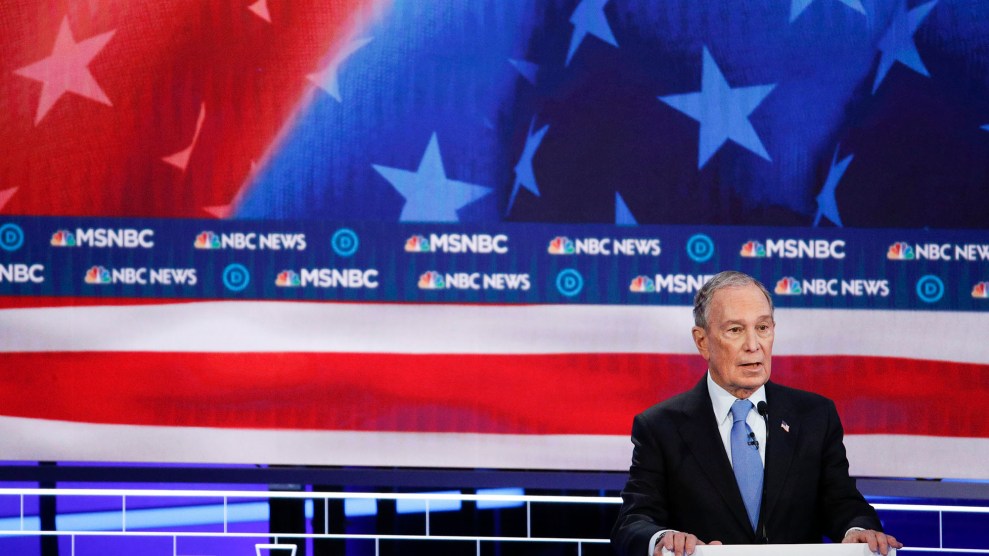

On Wednesday, after the debate’s donor thresholds were scrapped and Bloomberg qualified for the showdown in Las Vegas, he was hit with not just the harshest scrutiny he’s faced during the 2020 presidential primary, but perhaps some of the toughest scrutiny he’s faced at any point in his political career. Sanders, the frontrunner, was more than happy to cast the Wall Street–defending billionaire as the antithesis of his political revolution. But the other four candidates, led time and again by Elizabeth Warren, took turns highlighting and condemning several decades of comments, policies, and contradictions. Bloomberg’s greatest asset in his run for the presidency has been the ability to air his own message, while deflecting whatever comes his way—a trait BuzzFeed compared to a “Trump-like Teflon.” But up until he took the stage at the Paris casino, it had never really been tested.

Bloomberg didn’t do himself many favors. He stammered a bit and sounded upset when people interrupted him. If voters are migrating away from Joe Biden because of what they’ve seen on the debate stage (as a good number of them have intimated to me), Bloomberg didn’t do much to position himself as the next in line. But most of his problems were longstanding—the knives were out for his record, and it started almost as soon as the debate was underway. Sanders got the ball rolling by broaching Bloomberg’s embrace of the stop-and-frisk program, which subjected black and Latino New Yorkers to unconstitutional racial profiling and, in many cases, jail time. It was “outrageous,” Sanders said, and—with an eye on the “electability” argument Democratic primary voters seem to love—the kind of record that would depress turnout against Trump this fall.

Next, it was Warren’s turn. “I’d like to talk about who we’re running against,” she said. “A billionaire who calls women fat broads and horse-faced lesbians—and no, I’m not talking about Donald Trump. I’m talking about Mayor Bloomberg.”

That was a nod to Bloomberg’s long record of sexist comments. Bloomberg didn’t have a chance to respond before it was someone else’s turn. “I don’t think we look at Donald Trump and say we need someone richer than him in the White House,” added Amy Klobuchar. Pete Buttigieg helpfully pointed out that Bloomberg was, at least for a significant chunk of his career, a Republican. Later, Biden brought the subject back to stop and frisk, pointing out that Bloomberg’s defense of the policy has been inconsistent, and that the Obama administration had to send someone in to monitor the program—a move that Bloomberg slammed the president for at the time. Biden called Bloomberg’s policy “abhorrent.”

If it felt as if all these criticisms had been bottled up for months and maybe years, and then just let loose, it’s because, well, they kind of were. Rich, powerful, mostly white men manage to largely insulate themselves from the harshest kind of criticism or consequences, and Bloomberg has to an unusual degree controlled the messaging about his company and now his campaign. As my former colleague Nick Baumann noted, it’s hard to imagine someone like Bloomberg ever subjects himself to such sustained criticism.

I genuinely wonder whether Bloomberg has ever faced this kind of unrelenting criticism from people in the same room as him.

— Nick Baumann (@NickBaumann) February 20, 2020

I don’t want to suggest that New York politics is easy. We know most of what we know about Bloomberg because of the doggedness of the New York City press. But Bloomberg has also spent most of his career cagily evading accountability, and there’s a certain fatalism, maybe, that this stuff has just been “out there” for a while now and hasn’t really hurt him. Leading up to Wednesday, his campaign had twice issued statements saying that Bloomberg had apologized for some of his crude remarks about women, but notably never specified what he was supposed to have apologized for. In any event, a secondhand apology isn’t quite the same.

He’s certainly never had to face these questions on a debate stage, on national television, from a woman who desperately wants the same job he does. So the most intense moment of the night came a few minutes after the argument about stop and frisk, when Warren returned to the question of Bloomberg’s treatment of women. Bloomberg mumbled about how many women actually liked working at his company, and Warren—who has been trying to get this exact story to stick for a while now—really let him have it.

“I hope you heard what his defense was: I’ve been nice to some women,” she said.

Warren brought up the fact that women who worked for Bloomberg are blocked from speaking out because of restrictive nondisclosure agreements, challenged him to release them to speak freely, and when Bloomberg said that complaints of sexism could simply be chalked up to people who “didn’t like a joke I told,” she landed what my colleague Pema Levy called “the night’s biggest blow”: “The question is: Are the women bound by being muzzled by you? And you could release them from that immediately…We are not going to defeat Donald Trump with a man who has who knows how many nondisclosure agreements and the drip, drip, drip of stories of women saying they have been harassed and discriminated against.”

In the quiet hours before the debate on Wednesday, most of the candidates who would take the stage found their way to the Palms resort and casino, where members of the powerful Culinary Union were picketing the resort management in the hopes of coaxing them to the table for contract talks. It got to be sort of a weird little routine: A candidate would show up (Warren brought doughnuts) and all of a sudden the rest of the picket line would thin out and a mob of cameras and reporters would take a break from filming the dancing workers at the far end of the line to converge as if summoned by some irresistible force. The workers continued marching while the candidates did their rotation and then, a few minutes later, some other candidate would take their turn and the cycle would repeat.

Bloomberg wasn’t part of this, of course, because he isn’t even competing in Nevada. His absence, and at the same time his looming presence, has felt like dark matter, giving the first-in-the-West caucuses a weird feeling, like something very important is exerting a force on the proceedings that’s invisible to the electorate here. But after Wednesday, Bloomberg isn’t just an abstract polling average and a blank checkbook; he’s a real candidate with a whole lot of weaknesses. And come tomorrow, a whole lot of bruises.