Mother Jones illustration; Michael Mullenix/Zuma; Getty

Twenty first graders had just been killed in their classrooms in Newtown, Connecticut, and Michael Bloomberg wasn’t in the mood to pull punches. During a December 16, 2012, appearance on Meet the Press, he criticized President Barack Obama, who, he argued, had failed to keep those children safe from gun violence. Obama hadn’t “fought hard” to enact gun restrictions, despite having “campaigned in 2008 on an assault weapon ban,” Bloomberg told David Gregory, the show’s host. Bloomberg added that “the only gun legislation that the president has signed” had, in fact, relaxed gun laws, granting the right to carry firearms in national parks and on Amtrak. “I assume that’s to stop the rash of train robberies,” he snapped. “This is ridiculous.”

Whatever you think of Bloomberg’s statements, he was certainly speaking from a place of authority. No other prominent elected official had done as much as the billionaire businessman—who was nearing the end of his third and final term as New York City’s mayor—to elevate the issue of gun control, which had for years languished in the political backwater. He’d spent the previous six years leading Mayors Against Illegal Guns, a coalition of city executives whose goal was to help law enforcement remove illegally obtained firearms from their communities. During the 2012 election cycle, he had shelled out millions of dollars backing a handful of candidates who support gun control. For months, he’d been pushing the Obama administration to take action after a shooting that left 12 dead in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater.

Gregory asked Bloomberg what he’d do if he were president. The mayor didn’t hesitate. He said he’d close the so-called “gun-show loophole” that allows people to buy firearms without a background check and that he’d issue an executive order to ensure that the database used for background checks is kept up to date. Despite his criticism of Obama just moments earlier—and the fact that assault weapons had been used in both Newtown and Aurora—an assault weapons ban apparently wasn’t on Bloomberg’s to-do list, either.

By then, Bloomberg’s platform had become a well-rehearsed routine. After years of federal inaction on gun control, Sandy Hook had, in the most tragic circumstances, given him an opportunity to advance the moderate, poll-tested agenda he’d been laying the groundwork for. And that’s exactly what he tried to do: In the weeks that followed, Bloomberg and his allies crafted and lobbied hard for an expanded background checks proposal known as the Manchin-Toomey amendment. The bill, which angered some long-toiling gun control activists but won the Obama administration’s backing, was ultimately derailed by a Senate filibuster. But the effort cemented Bloomberg’s status as the de facto kingpin of the gun control movement, vested with authority that would only increase in the years to come.

The story of how Bloomberg elevated himself to such a position is less about guns than about Bloomberg—specifically, his skills as a political tactician. He seized control of the movement at a time when its key players were weak, forging crucial alliances and dispensing enormous sums of money to bend the gun control world to his will. And the way Bloomberg did it—under circumstances that bear similarities to the 2020 Democratic primary—offers lessons for understanding his current White House bid.

“The overriding feng shui of Bloomberg’s folks is that they [think they] are the smartest kids in the room and can do almost anything better than almost anyone else,” a former senior employee of Mayors Against Illegal Guns says. “The gun issue is Exhibit A for them.”

To understand how Bloomberg could come to wield such influence, it’s important to remember what the gun control movement looked like 14 years ago, before he became one of its top players. In short: It didn’t look like much. After a Democrat-held Congress passed bills enacting a federal background check system and a 10-year ban on assault weapons in the 1990s, the party lost control of Capitol Hill; when Al Gore lost the presidency in 2000, pundits blamed his defeat partly on his support for gun control. During the George W. Bush administration, Congress passed bipartisan legislation to prohibit lawsuits against gun manufacturers and allowed the assault weapons ban to expire. In 2006, Democrats regained control of Congress, in part by fielding a slate of candidates touting “A” ratings from the National Rifle Association. The Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence—then the movement’s most important group—was starved for resources after years of dismal fundraising and was forced to lay off a chunk of its staff.

Understanding why Bloomberg embraced the issue when so many others were running away from it also requires Democrats to grapple with an uncomfortable reality: The history of the gun control movement is closely intertwined with the “tough on crime” policies that progressives now decry. The assault weapons ban, after all, had been part of the massive 1994 crime bill that helped exacerbate the era of mass incarceration. “The question you asked of any piece of legislation was, ‘Is law enforcement supportive?” recalls Brian Malte, who was a senior official at Brady from 1996 to 2016. “If not, the recommendation was that you not take up that bill.”

Bloomberg had entered office in 2002 with his own “tough on crime” platform and pursued a series of controversial, often discriminatory law enforcement initiatives. That included the aggressive use of warrantless stop-and-frisk searches in which cops detained civilians—disproportionately people of color—to look for weapons. The 2003 shooting deaths of two African American police officers had loomed over Bloomberg’s reelection campaign, raising greater concerns about how his administration was keeping guns out of the hands of criminals. As mayor, Bloomberg would go to hospital bedsides and waiting rooms to meet with the families of law enforcement officers shot in the line of duty.

According to Everytown for Gun Safety—the successor group to Mayors Against Illegal Guns—Thomas Menino, the late Boston mayor, first approached Bloomberg in 2006 with the idea to convene a group of mayors to “discuss how to stem the tide of gun violence and how to make their cities safer.” Around that time, according to multiple sources, Brady president Paul Helmke—a former mayor of Fort Wayne, Indiana—also encouraged Bloomberg to lend his political brand and fortune to the struggling movement. Helmke had been working with pollster Mark Penn, now famous for his role in Hillary Clinton’s failed 2008 presidential campaign. Penn’s business partner, Doug Schoen, has long been Bloomberg’s pollster. The two had put together a pitch deck proposing a new frame for the gun debate: Illegal guns.

“It tested better, and it allowed us, Democrats, [and] gun control activists to take the high ground of law enforcement,” a former Bloomberg aide familiar with the presentation told Mother Jones. Helmke brought the deck to Bloomberg—who at the time, like Helmke, was a Republican—and asked him to chair and give seed money to a new Brady-backed initiative called Mayors Against Illegal Guns.

This struck Bloomberg as a good idea, one that a former staffer described as both a “head and heart interest” for the mayor. But at the urging of longtime aides like Kevin Sheekey, who now runs his presidential campaign, and John Feinblatt, who leads Everytown, Bloomberg opted to do it independently of the anemic Brady Campaign. “It was, among some people who worked with the mayor, a conscious effort to pick an issue around which he could raise his national profile,” the former staffer recalls. “What the fuck did we need Brady for?”

So Bloomberg and Menino held a summit at Gracie Mansion, New York’s official mayoral residence, in April 2006 with 15 other mayors to begin to chart the organization’s course.

Sources familiar with Mayors Against Illegal Guns’ early days said the desire to turn the issue into a political winner for Bloomberg helped drive the strategy. A spokesperson for Everytown calls this assertion “entirely false” and says gun control has “only recently” become a political winner. But opposing the NRA was good politics in mid-2000s New York, and it offered Bloomberg an open platform that Republicans and Democrats alike had refused to occupy.

But building a nationwide campaign would require reining in the mayor himself. The public record is littered with Bloomberg statements that would likely alienate gun-owning Americans and their GOP representatives, such as his 2014 declaration that anyone who wants a gun in their house must be “pretty stupid.”

“Any conversation that I was ever involved in where the mayor was present, he tended to be the most aggressive guy in the room,” a former adviser to the group recalls. “He has consistently, over a period of a decade, been walked back by his staff, all of whom were very focused on the fact that they would like him to be president one day and needed to be protected.”

So Mayors, as insiders called it, opted for an incremental, data-driven, “third way–ish”—in the words of one former aide—approach. By October 2006, the group touted 109 member mayors and an agenda filled with universally popular proposals that were small and achievable. “It’s not ‘gun control,’ it’s ‘crime control,’” another former aide recalls of the messaging strategy. Tightening background check requirements, which had nearly 90 percent support, was in. Bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, which polled less favorably, were out. “The notion of keeping guns out of the wrong hands and regulating access to guns, rather than regulating guns themselves, polled a lot better,” the former aide says.

Mayors picked its battles carefully—it sat out the fight over the guns-on-Amtrak bill, for example. But it took just three years for Bloomberg to put up his first “W” against the NRA. In August 2009, the Senate rejected an amendment that would have allowed gun owners to carry concealed firearms across state lines, thanks to a massive lobbying push from Bloomberg and his team, relying on full-page newspaper ads, pressure from the group’s mayors—which by then numbered 450—and a message that weaponized Republican states’ rights rhetoric against them.

Money played a tremendous role: By the time the concealed-carry bill was defeated, Bloomberg had poured nearly $3 million of his own money into the cause. The spending would balloon in subsequent years; Bloomberg gave Everytown for Gun Safety more than $10 million in 2017 alone and has sunk $270 million of his own money into the movement. The alliances Bloomberg forged with mayors in his group were bolstered by grants awarded to cities so they could hire staff dedicated to cracking down on “crime guns.” Mayors Against Illegal Guns also doled out five- and six-figure sums to existing gun control groups and gave seed money to Americans for Responsible Solutions, the group former Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords launched with her husband, Mark Kelly, a year after she was severely wounded in a mass shooting in Tucson.

Then there was the election spending: In 2012, when Bloomberg first bankrolled campaigns against NRA-backed incumbents, he prevailed in four out of seven races. “The only real question for us was, ‘At some point, are we spending so much money there that it’s distasteful and looks as though we’re trying to buy an election?’” a former Bloomberg aide says.

The gun violence prevention movement had been relaunched, and the rest of its activists fell in line—in some cases begrudgingly. “They breathed new life into the movement,” a senior official of another gun control group tells me. “The ability to win was the wakeup call of, ‘Oh, we could actually do this.’”

Then came Sandy Hook and the failed push to close the gun show loophole. The background check legislation that came to be known as Manchin-Toomey had been hammered out in a secret meeting at Manhattan’s Odeon restaurant in early 2013 by Feinblatt, Mayor’s Against Illegal Guns executive director Mark Glaze, and a top gun industry lawyer, who had been included in the conversation to help bring Republicans and firearms companies on board. “Because Democratic Party leaders had been so against this, there were no staff on the Hill who knew anything about gun policy,” Arkadi Gerney, who preceded Glaze as Mayors’ executive director, recalls. “That created a void that Bloomberg, especially, could step into.”

Manchin-Toomey would have required a background check for most commercial gun sales, but other private sales and transfers would still have been permitted without a background check. It also contained a number of sweeteners for the gun industry—such as making it easier to sell and transport certain firearms across state lines—that would have weakened existing gun laws. That alarmed many gun control activists, but Bloomberg’s influence was so strong in Washington that he managed to shut down their attempts to lobby for anything stronger. “Sometimes you’ll get a heads up on what we’re doing, sometimes you won’t,” a former policy director for a rival gun control group recalls a Mayors official telling him at the time.

“A lot of activists were having meetings on the Hill arguing against [Manchin-Toomey’s] provisions, but then we’d hear it was moving forward,” an official of another gun control group remembers. “They were weakening an existing background checks law, and we had no idea who in the gun violence prevention movement was signing off on this.”

Despite the concessions to the gun industry, a handful of Democratic senators joined nearly every Republican to kill the bill. Some gun control advocates now fault that watered-down measure for weakening the movement. And they blame, in part, Bloomberg’s unwillingness to collaborate. Bloomberg’s presidential campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

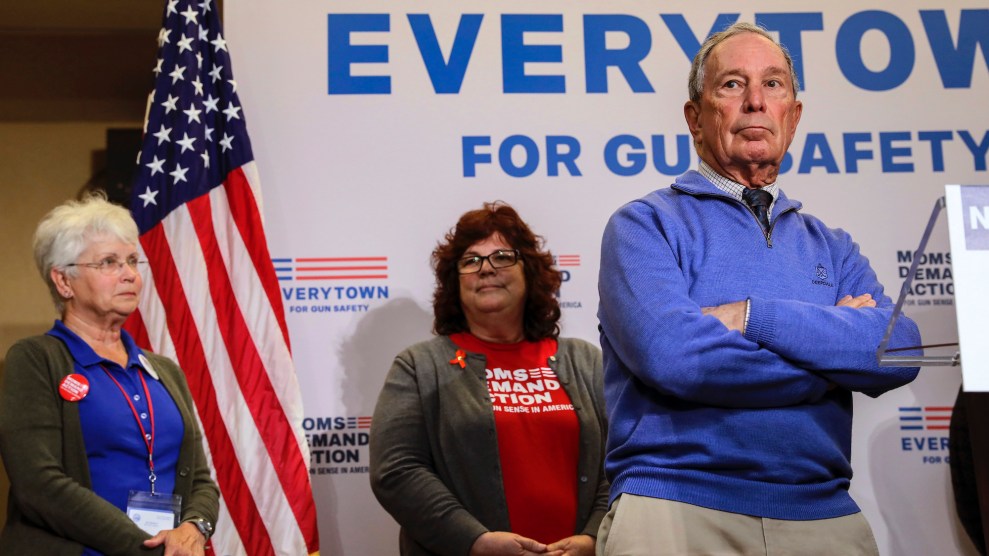

Since then, Bloomberg’s influence has only grown. In 2014, Mayors Against Illegal Guns merged with Moms Demand Action, the grassroots group founded by Shannon Watts, to become Everytown for Gun Safety. Watts’ organization was strong in volunteers but weak in infrastructure, and it needed a serious infusion of cash to continue. And Bloomberg recognized that Watts had built the one thing he could not outright buy himself: A grassroots army committed to the issue.

Dozens of elected officials have found their way into office thanks in part to support from Everytown’s money or Moms Demand Action’s grassroots network. And Bloomberg, who is no longer involved in Everytown’s day-to-day operations, has personally spent huge sums of money on state and federal races since 2012. He bragged about this record at a recent Democratic debate, saying that of the 40 House seats Democrats flipped in 2018, “21 of those were people that I spent a hundred million dollars to help elect.” He then appeared to nearly blurt out that he’d “bought” the new majority, before catching himself. A number of those lawmakers have endorsed Bloomberg’s White House bid, including Lucy McBath, a former Moms Demand Action spokesperson who now represents Georgia’s 6th congressional district.

Bloomberg came within a hair's breadth of saying he *bought* the Democratic majority in the House and caught himself as it came out of his mouth pic.twitter.com/DG0keVMo2J

— Brandon Wall (@Walldo) February 26, 2020

The implications for 2020 are clear. “The presidential campaign is relying on deep, long-standing relationships that he built with other elected officials around the country, and Mayors Against Illegal Guns is probably the biggest network for that that was built,” one former Bloomberg aide says.

Money is also a “pretty daunting opponent,” the aide adds, noting how Bloomberg turned a third-rail political issue into a feather in his cap. “There are very few issues that can’t be turned to your advantage if you have enough money to build the political infrastructure around them.”

But the rise of Everytown also reveals the limits of Bloomberg’s abilities. Over the past 14 years, Bloomberg and his allies have racked up many policy wins in state legislatures but have secured virtually no new gun control laws at the federal level. We’ll soon find out if his $500 million presidential campaign will fare any better.