Joe Biden speaks on the stimulus program in Cincinnati, Ohio, on July 9, 2009.Al Behrman/AP

Joe Biden stood before a packed room to deliver good news. At a think tank in DC, the VP geared up for a speech clearly tailored to serve as a legacy-building exercise, a signal for how he hoped to be judged as the leader of a crisis, not just the second-in-command. “The Recovery Act has played a significant role in changing the trajectory of our economy,” Biden declared at the Brookings Institution back in September 2009.

It was a peculiarly rosy outlook at that time. Banks had foreclosed on more homes in August than in any month since the mortgage crisis had begun. In October, the unemployment rate would reach its Great Recession peak, with one in 10 Americans out of work. Such woeful economic indicators made it hard to argue that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the $787 billion stimulus package had visibly turned the economy around.

But Biden had brought his own data. Economists estimated that three-quarters of a million jobs had been “created or saved” thanks to federal spending. Thousands of infrastructure projects in airports, highways, and bridges were underway—many of them on track to finish ahead of schedule and under budget. “Instead of talking about the beginning of a depression, we’re talking about the end of a recession eight months after taking office,” Biden declared.

Biden spoke for over an hour, with a polish that kept the ever-colloquial son of Scranton to just five “folks.” As he did, he sung his own praises, noting that the early predictions that a recovery of that size would have “millions of dollars wasted” ended up being “the dog that didn’t bite.” He also admitted fault: The onerous process his office had implemented to distribute funds moved too slowly in the critical first 100 days.

Throughout the bruising 2020 Democratic primary, Biden’s liberal competitors and critics have fixated on Senator Biden, the foreign policy–savvy career politician whose past opposition to busing and abortion put him out of step with his party’s base—as did his kid-glove handling of corporate America, most often vilified through his support of the 2005 bankruptcy bill that sided with companies over consumers. Those same detractors also hammer the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act itself: The stimulus package signed by President Obama was too small, it made its way to hurting workers too slowly.

But when it comes to Vice President Biden and his role in that recovery, the critiques largely cease. Obama tasked Biden with overseeing the stimulus and pulling the country out of recession—a position that added merit to Biden’s folksy, middle class ethos. By all accounts, what he oversaw succeeded: The Recovery Act jumpstarted what would become the longest uninterrupted stretch of economic growth in US history, and an analysis from its oversight board found that, by the end of 2011, only 0.001 percent of the nearly $800 billion spent was ever attributed to waste or fraud. And it was successful because, according to those who knew him, Biden was an adept manager who set the tone and surrounded himself with the right people to ensure oversight ran smoothly.

“Biden’s role as vice president was much more positive than his role as a senator from Delaware,” says Jeff Hauser, founder of the left-leaning Revolving Door Project, who has been critical of Biden’s ties to Wall Street. “I do think he did a good job running the Recovery Act. He was very focused on avoiding scandals, and he succeeded.”

But some say that devotion to oversight also slowed the recovery, and that, in combination with a failure to sell the Recovery Act’s merits before its effects took hold, haunted Democrats during elections in the years that followed. Now, in the midst of a pandemic-induced economic collapse, Biden must again try to sell that recovery and his role in it as he tries to make his case against Trump—something he’s struggled to do as his campaign goes digital and Trump blankets the airwaves with his press conferences-turned-campaign rallies each night. He also needs to prove to Democrats skeptical of the Obama administration’s response to the crisis that he’s learned the lessons of how the Great Recession’s recovery fell short.

Just two weeks after Barack Obama chose Biden as his running mate, the federal government took over failing mortgage lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and AIG followed. At the end of September, Congress passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act to pump $700 billion into rescuing the banks. When Obama took the oath of office on January 20, 2009, the unemployment rate had risen to 7.6 percent, up roughly three points from the year before. Home foreclosures had increased by 81 percent over the previous year—even as a number of lenders suspended foreclosures in the last quarter of 2008.

As its first order of business, the new administration rushed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act through Congress. The $787 billion in the bill was allocated to three buckets: increases in unemployment compensation and safety net programs, and tax breaks to get money back in Americans’ pockets; tax cuts and incentives for businesses to resume operation; and infrastructure projects to immediately put people back to work. But when Obama signed it into law that February, no one in either political party liked it. Progressives deemed it woefully inadequate to stop the economic bleeding, a byproduct of the Obama administration compromising with itself before bringing it to a spend-shy Congress that further docked its reach. Republicans regarded it as a pork-filled liberal wishlist of government overreach.

A week before his swearing-in, Biden told the New York Times he’d like to “restore the balance” of the office after eight years of Dick Cheney’s unchecked authority, aiming instead to be a trusted adviser of the president. In the spirit of that advisory role, he wrote Obama a memo detailing the need for a White House official to oversee the vast sum of money—to make sure it was spent quickly and without waste. When Biden shared the memo with Obama over one of their weekly lunches, the president named Biden to that role. “Never write a memo to the president suggesting that a job be undertaken that you don’t want to have,” Biden recalled that day at Brookings.

In his new capacity, Biden declared himself the “vehicle” for helping cities and states get back on their feet. He spent hours on the phone each week with governors, mayors, and county executives to talk about their federally funded projects and address their concerns about the flow of funds, promising state or local officials a 24-hour turnaround time on any calls they made to his office. But in exchange for helpfulness, Biden demanded accountability—“not in a draconian way,” he clarified at the first Recovery Plan Implementation meeting in February 2009, “but to actually get this done.” He vowed to take a “follow the money” approach, using the authority Obama had granted him to convene the Cabinet to ensure money flowed swiftly through the agencies to stimulus-backed projects. During his first two years in office, Biden held 22 Cabinet meetings on the topic—more than Obama held on any subject during that same timeframe.

At the end of 2009, more than 90 percent of stimulus funding recipients had reported how they’d used that money. Biden allowed that rate was “remarkably high,” but slammed the laggards’ “missing information” as “unacceptable.” By the following spring, a mere 1.6 percent of contracts were unaccounted for. The only scandal to emerge was the bankruptcy of Solyndra, a solar power manufacturer that received a $535 million loan from that stimulus bucket that later went belly up and was subject to an FBI and congressional investigation. “If you go back and look at the things [Republicans] tried to blow up, you can see that they’re tiny peanuts as a share of the total,” says Austan Goolsbee, who served on Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers at the time.

Those who worked alongside the vice president at the time lay much of that success of Biden’s management style. Biden frequently waded into the details of the over 100,000 Recovery Act projects. As journalist Michael Grunwald details in The New New Deal, Biden would grill Cabinet secretaries to share the names of projects falling behind schedule, call the local officials responsible for those projects, and threaten to take their money away. “You don’t say no to Joe!” Biden would say. The former vice president also blocked 260 proposed projects that he feared would make the efforts look silly—including, as Grunwald notes, a “$120,000 Army Corps of Engineers plan to print brochures advertising a lake cleanup in Syracuse.”

Goolsbee says Biden deserves “a great deal of credit” for both his own efforts but also for the organization he designed. It was Biden’s idea, for example, to name Ed DeSeve as a special advisor in charge of keeping the 28 agencies that channeled the billions into various projects on deadline while ensuring they didn’t step on one another’s toes. Those who worked with Biden at the time also praise the people he surrounded himself with, such as his chief of staff, Ron Klain, whom Obama later tasked as the “Ebola czar.” “The vice president conveyed to us that he didn’t want to be bitten by one dollar from this act,” says Jared Bernstein, who served as Biden’s chief economist at the time. “That message rippled through Ron Klain, to myself, to our respective staffs. We either had to implement this well, or get slammed for not doing so.”

Biden’s oversight earned high praise from Obama, who lauded the “complete transparency” of the stimulus in January 2010. “You guys can go on the White House website and look at every single project that has been awarded a recovery act grant—every single one—and scrutinize them,” Obama said. “You know who the contractors are. You know who’s doing the work. You know when it’s supposed to be finished.”

The tradeoff of “complete transparency,” however, was speed. Before a federally funded project could move forward, it had to go through the oversight process, which baked in delays. Journalist George Packer, writing for the New Yorker in 2010, captured this frustration through the eyes of Rep. Tom Perriello, who had been elected to represent Virginia’s 5th District the same year Obama won the presidency.

“We were absolutely determined to get the money out quickly, but that sometimes was in tension with our also admirable goal of providing transparency of every dollar spent,” Perriello says today. He recalls being disappointed that companies who could have put contractors and construction crews back to work right away wasted months as they waited for, as Packer put it, the administration’s “painstaking approach” to run its course.

“I know I got criticized in the front end of this for being too fastidious about how the money went out, to make sure we had the mechanisms in place,” Biden admitted in April 2010. But that concession did little to comfort the 15.3 million of Americans who were still unemployed. And Biden knew that. “When you lose 8 million jobs in this Great Recession and you keep it from being 10 [million], that’s no solace to the 8 million who don’t have a job, man,” he told labor leaders in Florida that March.

As Biden crisscrossed the country to stump for fellow Democrats during the 2010 midterm elections, he tried to sell the stimulus, asserting taxpayers had “gotten their money’s worth” out of the stimulus package. But any signs of life had disappeared over the summer as dismal unemployment numbers and a gutted housing landscape made headlines. That November, Republicans seized control of the House as Democrats like Perriello lost their seats to GOP candidates who pinned the lackluster recovery on the president’s party. “The recovery was already underway, but not with enough time or strength for people to have felt it yet,” Perriello says. “All people knew about the stimulus was the price tag, not that it prevented a Depression.”

“We got ourselves into trouble when we were talking about improvements before people could see them or feel them,” says Bernstein, recalling that he and others used the phrase “green shoots” to describe the early signs of economic growth. “That was very unresponsive to people’s experiences.” And with the GOP in control of the House, Congress’ will to keep the recovery going ceased. “That single act wasn’t a horse that could pull the whole sleigh,” Biden told Grunwald.

Now, Biden is the presumptive Democratic nominee, and the former veep finds himself tasked with selling that recovery again. The pandemic has swallowed the 2020 campaign whole—including the very nature of campaigning itself. Biden’s challenge is to contrast how he is better suited to lead the country out of the virus and its economic devastation than its current leader. So far, Trump’s failures play right into Biden’s experience: None of the oversight mechanisms Congress required of its $2 trillion emergency relief package have come together as the government begins distributing billions in aid, and states have struggled to dole out the promised unemployment benefits to jobless workers, citing slowness from the federal agencies responsible for handing them cash.

The parallels between this moment and his role 12 years ago hasn’t escaped Biden, and on the (virtual) campaign trail, he’s touted his “Sheriff Joe” badge as he recalls the lack of scandal and Obama’s praise. His criticism of President Trump has centered on what Biden calls a “false choice” of choosing between fighting the virus and recovering the economy, noting that it is the federal government’s responsibility to take care of workers until the pandemic subsides. He’s emphasized the need to move quickly on getting cash into the hands of jobless Americans and small businesses, another Great Recession lesson heeded. The visibility of these statements, though, hasn’t translated into confidence in his abilities: A recent Business Insider survey found that respondents viewed New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and California Gov. Gavin Newsom as more trustworthy than Biden on the pandemic response.

In early April, the Biden campaign released a list of recommendations for implementing and overseeing the stimulus bill Congress passed in March, a flex that returns to his Great Recession bona fides. His campaign is reportedly working on a “broader case of what is going to be required not just over the next few months but over the next few years to adequately respond to what has happened,” Jake Sullivan, a senior Biden adviser, told the Wall Street Journal.

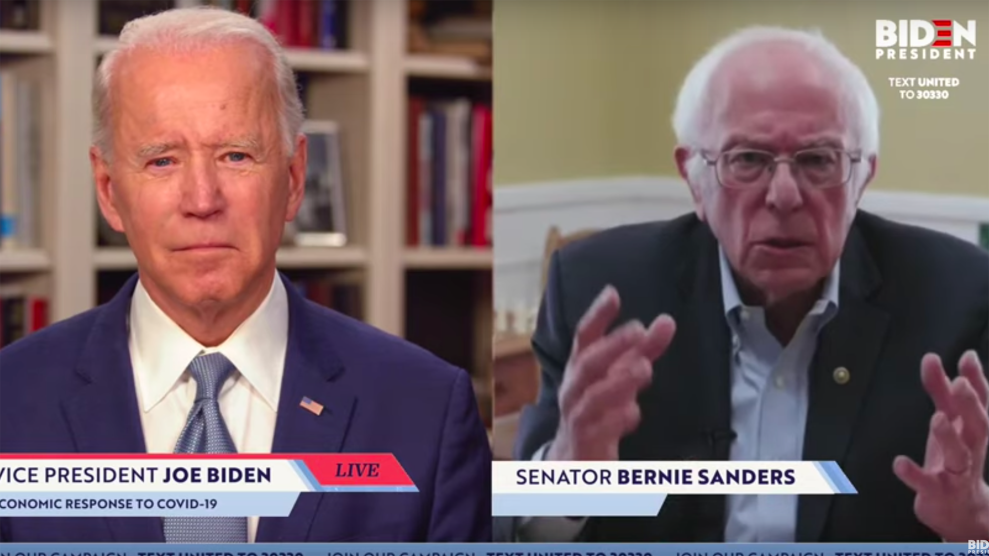

And whatever vision emerges in that plan is crucial to another priority Biden faces: Unifying his party, a vast swath of which is disappointed Bernie Sanders is not the nominee and was critical of the Obama administration’s reluctance to take a tougher stance against Republicans to keep the federal stimulus funding going. So far, those lefty critics are heartened by some of the advisers in the “kitchen Cabinet” Biden has enlisted. They include Bernstein, a left-leaning economist with close ties to the labor movement; Richard Cordray, the first director of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau; and Heather Boushey, who runs the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a left-leaning economic think tank.

“If Joe Biden learned the right lessons from how Mitch McConnell and Republicans handled themselves during the Great Recession,” says Adam Green, a co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, which backed Elizabeth Warren in the 2020 primary, “which is that they don’t operate in good faith, then he will have a very powerful opportunity to unite the Democratic Party behind a theory of the fight—perhaps in a way that Bernie Sanders couldn’t.”