Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders greet each other before a Democratic presidential primary debate on March 15.Evan Vucci/AP

The 2020 race was shaping up to be a banner election for small donors. The major presidential candidates have reported record hauls from contributors kicking in $200 or less, harvested by campaigns custom-built to draw as many of those donations as possible. That was before the coronavirus pandemic sparked a national crisis, abruptly halting the US economy and throwing millions out of work. The outbreak—along with its many uncertainties—has posed a dilemma for political fundraisers: Can they still count on small donors? And how do they appeal to such contributors in the midst of a public health and economic cataclysm?

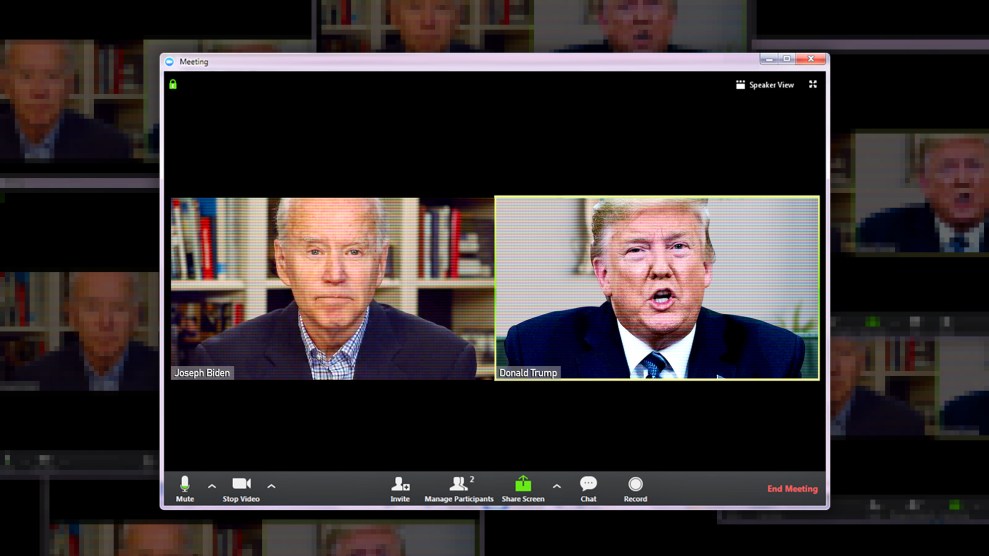

Small donors have always been part of the scene, but with the rise of digital technologies—and populist candidates—they have become increasingly important in recent elections, not only as a source of funding but as a sign of voter enthusiasm. During the 2020 cycle, Bernie Sanders has raised nearly $100 million from small donors, more than half of his total. His Democratic rival, Joe Biden, has been slammed for relying on high-dollar fundraising events, but he too has received a historic level of small-donor support. Nearly 39 percent of his campaign war chest has come from people giving $200 or less. (Donald Trump, who crushed previous online fundraising records during his 2016 run, has so far raised more than $115 million from such contributors during the 2020 race.)

“The number of people who excited Democratic voters was really leading to an unprecedented amount of investment,” says Matt Compton, the deputy digital director for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign who is now director for advocacy and engagement at Blue State, a Democratic digital consulting firm. “Now, the situation is inevitably going to be different.”

Few Americans donate to political candidates, and even fewer give small amounts: An analysis from campaign finance watchdog OpenSecrets found that slightly more than half of 1 percent of Americans donated more than $200 to presidential campaigns in 2016. But those who do make small-dollar donations often do so because they feel an emotional connection to the campaign. “If you give $2,800, it’s typically in exchange for close-up exposure to a candidate,” says Teddy Goff who ran digital fundraising for President Obama’s 2012 reelection. “That’s not happening for $5 or $25—those donors are doing it because they believe in the candidate.”

The Federal Election Commission doesn’t require campaigns to turn over detailed information on donors who give less than $200—only the lump sum raised from them. However, in recent years both Democratic and Republican campaigns have begun outsourcing their small-dollar fundraising to groups like ActBlue and WinRed, which do provide more details on who these donors are. Sheila Krumholz, executive director of Open Secrets, says this data indicates what you might expect: Small donors are among those who are likely to be hardest hit by the economic collapse.

“We do know that based on their occupation and employers, that small donors are more representative of the middle- and working-class occupations, and the reports are those people are more affected by the economic fallout now and unemployment,” she says.

Campaigns are already seeing a drop off in small-donor giving, says Shelby Cole, who led digital fundraising for Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 senatorial campaign, which raised 45 percent of its $79 million from small-dollar contributions. “Folks I’ve spoken with who are working for digital firms who are raising money for senate races and gubernatorial races have seen the money drop since the news of coronavirus really started taking off,” she notes.

ActBlue says its House and Senate candidates saw a 13 and 6 percent drop-off, respectively, from the first two weeks in March to the last two, as the scale of the pandemic’s economic devastation became clearer. But a spokesperson for the organization also noted that candidates made fewer donation asks during that period, hitting pause on their pre-pandemic messaging and strategy as they hastily hashed out how to retool their campaigns to suit the current moment.

As the outbreak-inflected economic pain mounts, one thing campaigns are grappling with is how to ask for contributions. Nearly 10 million Americans filed for unemployment in recent weeks; millions more are expected to meet a similar fate in the weeks ahead. The Federal Reserve estimates that the pandemic could cause unemployment to hit 32 percent—with 47 million Americans out of work. Under those conditions, fundraising emails can seem tone deaf and potentially turn supporters off. Goff says he’s noticed several campaigns have removed the “Donate” button from recent mass emails. “I don’t think anyone particularly wants to be made the poster child of opportunistic fundraising off a national crisis,” Goff says. Cole likened the pandemic to a national tragedy, such as a mass shooting. “That’s a moment where you pull the fire alarm and say we’ll stop fundraising for a while to give readers space to grieve,” she says.

Some candidates are still seeking donations—but for pandemic relief, not their campaigns. Blue State’s Compton points to the way the Sanders’ campaign repurposed its “Donate” button in recent weeks to help raise money for COVID-19 causes. Earlier this week, Biden did the same. The move signals a campaign’s values, Compton explains, which can go a long way in helping forge connections with voters that can pay dividends later on.

When appealing to small donors in this environment, Compton says, it’s wise for campaigns to underscore how these contributions are powering their newly retooled campaigns. Last week, Biden took a swing at this in his first email newsletter (a new medium the former vice president is now using to connect with voters), explaining that “online donors like you” are providing the “funding to pay staff, make videos, do outreach with voters, and plan out our path to taking down Donald Trump.”

Other campaigns and political organizations are getting more specific. Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), who’s up for reelection this year, asked donors to consider giving to his “digital program,” which would fund “online voter registration training, our text and phone banking tools,” and “virtual town halls with Mark.” Supermajority, a women’s political advocacy organization, told its supporters about the work its team is now doing remotely, which now includes amplifying the messages from partner organizations who advocate for those on the front line of the pandemic, such as domestic workers and caregivers, who are disproportionately women of color. Compton notes: “It takes a whole new measure of radical transparency—unpacking the value of the grassroots donation. You’ve seen folks get in the weeds talking about how their campaigns are changing.”

Cole predicts that some previously successful fundraising tactics, such as promises of matched donations or apocalyptic subject lines urging immediate contributions—the kind of “churn-and-burn” fundraising that prioritizes quick action over developing a message that brings donors back to give repeatedly—may not fare well in the current atmosphere. “I’m really curious to see how those fear-based programs pan out,” she says.

Political firebrands seem to have a natural advantage when it comes to small-dollar fundraising. In 2018, the candidate who had the largest percentage of money coming from small donors? Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Second? Republican Duncan Hunter. The list of top small-dollar fundraisers during that election cycle also includes household names from both parties, such as Reps. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), and Jim Jordan (R-Ohio.).

Clearly, certain candidates—and their media-friendly messages—have an edge, but can it be maintained? Candidates who message well, especially off voter angst, might still be able to maintain small-donor support. Open Secrets’ Krumholz says that if people are troubled or economically suffering, it may encourage them to give if a candidate can convince them it will help.

“It remains to be seen whether they stop giving, because they may view this as something they might have to dig deep to continue supporting because many may feel their economic future may depend on it, on both sides,” she says.