A resident writes down the Mississippi unemployment benefit website in Jackson, Mississippi, on April 2.Rogelio V. Solis/AP

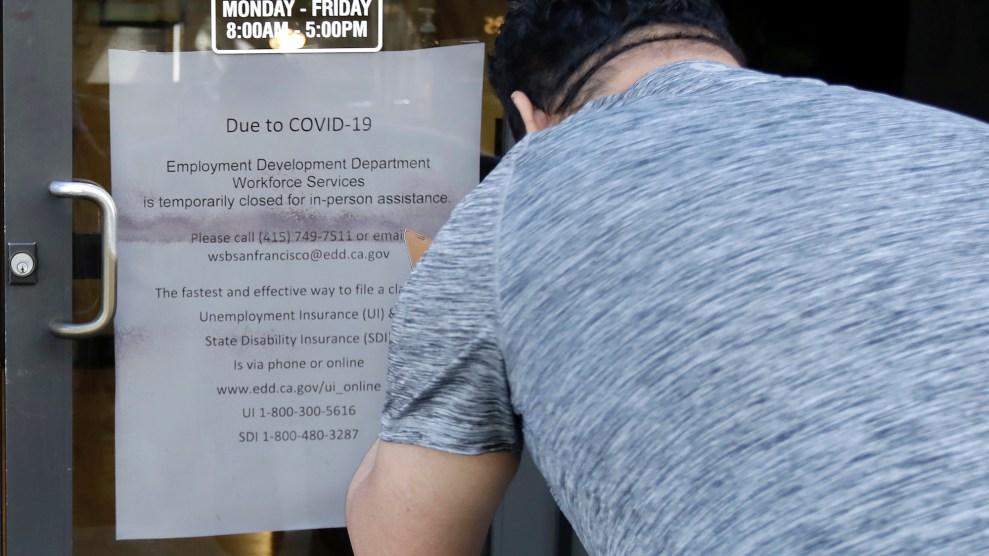

The 6.6 million Americans who filed for unemployment last week have earned themselves a grim superlative: They, along with the 3.2 million people who filed the week before, mark the fastest-growing unemployment disaster in recorded US history.

These early numbers don’t tell us exactly who these jobless workers are, but we have some clues. Major retailers, which have closed stores after government orders to shelter in place, have furloughed staff without pay. There have been sweeping layoffs in the food service industry, which employs an estimated 15.6 million Americans, as major suppliers cut staff and most states limit restaurants to takeout only.

These layoffs have been especially bad for two groups—namely, the same people who were particularly screwed over in the last recession: women and people of color. National unemployment numbers haven’t been broken down by demographics yet, but state numbers are looking dire for these groups. Minnesota has reported that women make up nearly two-thirds of new unemployment applicants. In pre-pandemic times, they typically accounted for only a third of them.

The retail industry accounts for 10 percent of all private sector jobs, and the retailers most affected employ the most women. Almost half of the workers employed by restaurants are people of color—and those workers are concentrated in the sector’s poorest paid positions. The low pay that accompanies these positions doesn’t really allow for the sort of long-term savings that could soften the blow of a lost job. The median hourly wage for a retail sales worker, for example, is $11.70, and it’s just $10.47 for restaurant servers. Congress passed legislation last month to increase unemployment benefits for the millions of Americans who’d lose their livelihoods as the pandemic raged, but for women and workers of color, that might not be enough. That’s because they’re likely to be among those who were never made whole after the Great Recession 12 years ago.

“Recovery had been uneven,” says Nicole Mason, president and CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “The gains of the economy did not really trickle down to women or people of color in the ways that we might have expected.”

The end of the last recession marked the longest sustained stretch of economic growth in US history, but the benefits weren’t reaped universally across all Americans. A report from IWPR in September 2011 found that 39 percent of women—including 52 percent of Black women and 48 percent of Hispanic women—reported difficulties in paying monthly utility bills, compared to just 26 percent of men who said the same. Even as the wider economy improved, those gaps persisted. A 2017 analysis from the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute found that, adjusted for inflation, Black men and women across all races are earning less than they did in 2007.

What led to such an uneven recovery? Much of it has to do with how the recession reshaped the jobs landscape. Positions in the public sector, which historically were committed to fair and inclusive hiring, faced steep cuts as states committed to austerity measures, and many of those jobs never came back. The gig economy—premised on part-time, low-wage, benefits-free labor—ascended in its place, disproportionately employing workers of color, who, like all women, are also overrepresented in minimum wage work.

Beyond wages, the wealth of those populations also took a tremendous hit during the Great Recession. Both women and people of color have less wealth than white men and were more likely to dip into their retirement or other long-term savings accounts to stay afloat. Crucially, homeownership and property values never fully recovered, particularly for households of color. In 2009, the median Black household wealth dropped 53 percent, compared with just the 17 percent white households lost. “Home equity is used to start a small business, pay for retirement, and pay for college,” Mason says. “The last recession wiped all of that out.”

And so a wealth gap that persisted long before the Great Recession widened in its aftermath. In 2010, for example, the average white household had eight times the wealth of the average Black household. In 2014, white families had 13 times the wealth of their Black counterparts.

Those setbacks now form the fragile foundation for workers weathering this latest crisis. Women, still often relegated to the role of family caretaker, will find themselves particularly squeezed as dwindling workforce meets new demands at home. “This is a gendered crisis,” explains Kate Bahn, director of labor market policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. “They’re facing a double burden of being really strapped in the paid economy as well as trying to care for their family members—maybe children who now need homeschooling, or elderly parents and a spouse at risk of getting sick.”

Disparities in health care coverage put these populations in a precarious position. Roughly a quarter of women delayed or declined medical attention due to costs in 2017, while only a fifth of men did the same, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey. That same year, a third of Black households skipped health care, compare to just 21 percent of white households, according to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking. “And that was in the good times,” says Christian Weller, an expert in labor and inequality at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “You can imagine what decisions people are making now.”

The natural conclusion of these conspiring circumstances leads to a doomsday scenario. Poverty rates will rise, Weller predicts, as people cut back on utilities, food, and prescription drugs necessary for preventative or long-term care. “Right now, there are a lot of things going wrong at the same time,” Weller says. “All of these inequalities already existed—they’re just magnified right now.”

The emergency relief bill Congress passed last week tried counteract the worst impacts of the current crisis, extending unemployment benefits to gig, freelance, and part-time workers for the first time ever. It also suspended six months’ worth of payments on federally held student loans, a burden that disproportionately affects borrowers of color.

But the experts I spoke with identified key shortcomings. Bahn wishes there had been more of an emphasis on labor standards and compensation, particularly for those who are on the frontlines of the pandemic response. Many of those who are still gainfully employed work in health care, regularly exposed to the deadly virus. Roughly three-quarters of hospital and health care workers are women, and while most of them are white, Black and Latinx workers are vastly overrepresented among home care and nursing home employees. “I’m just horrified thinking about people making $20,000 a year while dealing with the most vulnerable populations,” Bahn says.

Darrick Hamilton, an economist who studies disparities across race, says he’s particularly concerned about the one-time payment of $1,200 most adults will receive from the federal government. He says it’s neither sufficiently large nor sustained enough to keep people whole until the economy recovers. Hamilton also raised concerns about the small business loan program, which is already under scrutiny for how it plans to distribute emergency funds to firms. “Various small businesses—and particularly those that are black owned—are not capitalized to be able to withstand an economic downturn where you shut their business down for an extended period of time,” he says.

“I don’t think we’ve learned the lessons from 2008 at all,” IWPR’s Mason tells me. “We’re still targeting the largest amount of support for big businesses, and we’re doing so little for the people who will be suffering long after those businesses have rebounded.”