A rally in Georgia to protest the killing of Ahmaud ArberyJohn Bazemore/AP

A couple of days after the death of a 25-year-old Black man in Georgia named Ahmaud Arbery became widely known, a Mother Jones editor suggested to a group of reporters of color that we should publish something on the shocking video that was soon to go viral. It showed two white men chasing Arbery, who was jogging down a rural road in his own neighborhood, and gunning him down.

Our responses were identical: We were all so tired.

Is there anything new to be said about the killing of young Black men who are engaged in everyday activities until they attract the attention of white people who feel threatened and decide to kill them? How many times can we decry racism and beg to be seen as fully human? But while my colleagues and I felt exhausted, well-meaning people of all races littered my social media feeds with a rallying cry that is a variation on a theme as familiar as it is fundamentally empty. It boiled down to the old trope: “This is not who we are!”

Soon my exhaustion turned to frustration: In fact, this is who we are. And yet, by treating every single senseless death, every single racial profiling incident, every attack on Black people, every example of the disproportionate vulnerability of people of color to economic and now coronavirus devastation as some aberration, America is given a kind of absolution. Our racist society is off the hook.

First, consider what happened to Ahmaud Arbery. On February 23, Arbery, an avid runner, went for a jog in Satilla Shores, a majority white town in rural Georgia. He lived just two miles away with his mother. While he was jogging, several people called 911 to report that a Black man was running down the street. Gregory McMichael and his son Travis decided that a young Black man wearing shorts and running peacefully in their neighborhood must have been a burglary suspect. They chased him down and three shots are heard in the video, with the third fired at point-blank range. His death was caught on tape.

The case is now on its third prosecutor. The first one recused herself because she previously employed Gregory McMichael, who is a former investigator in the district attorney’s office. The second recused himself because his son works in the district attorney’s office that once employed Gregory McMichael. But before his recusal, he wrote a letter saying the father and son were innocent because of Georgia’s stand-your-ground laws and other laws that allow a private citizen to attempt an arrest if an offense is committed in his presence, or if he has immediate knowledge of it.

Eventually a video of the attack went viral, sparking a national outcry and demands for justice. Politicians across the ideological spectrum tweeted out statements decrying the killing of Arbery, and, naturally, vowing to fight for justice.

The video of #AhmaudArbery sickens me to my core.

Exercising while Black shouldn't be a death sentence.https://t.co/GV7GFju7tr

— Kamala Harris (@KamalaHarris) May 5, 2020

.@GBI_GA Director Reynolds has offered resources & manpower to D.A. Durden to ensure a thorough, independent investigation into the death of #AhmaudArbery. Georgians deserve answers. State law enforcement stands ready to ensure justice is served. https://t.co/ktLiPf7LoY

— Governor Brian P. Kemp (@GovKemp) May 6, 2020

Does all that outrage really matter? The national backlash over Arbery’s killing took place against the backdrop of a parallel crisis. The novel coronavirus has killed nearly 80,000 people in the United States and shows no signs of abating, thanks to the wholly incompetent response from President Donald Trump and his administration. Black people have disproportionately borne the brunt of this crisis, as my colleagues Edwin Rios and Sinduja Rangarajan showed in their investigation of the racial breakdown of death rates from COVID-19.

As the virus rages and continue to spreads, the country is hastily trying to adapt to social distancing, which involves the practice of wearing masks and staying at least six feet away from anyone you don’t live with. Public health experts have been saying for months that the only way out of this crisis is wide-scale testing, contact tracing, and social distancing measures until there’s a vaccine. But in typical American fashion, it appears we’re going to try to police our way out of it—even though over-policing has yet to solve any of society’s ills.

First there is the problem of wearing a mask while black. As I reported last month, the practice of covering your face is anxiety-inducing in the Black community:

For many Black people, weighing whether or not to wear a mask comes down to deciding whether or not to risk getting racially profiled, which could turn deadly, or contracting COVID-19, which could also turn deadly. “Am I going to risk my health or am I going to risk it all and pray that no one in this open-carry state mistakes me for a volatile?” George Wesley, a Black man from Newport News, Virginia, told me.

Then, many cities and states have criminalized standing too close together by deploying police officers to arrest or fine anyone defying the orders. It went as expected, at least for people of color. In New York City, photos and videos of police officers arresting Black people for not social distancing, while white people were able to sunbathe in parks and not social distance without being disturbed, went viral. On Thursday, Brooklyn’s district attorney’s office released the first data from social distancing arrests. Between March 17 and May 4, 40 people were arrested for violations. Thirty-five were Black. Four were Latino. One was white.

Mayor Bill de Blasio returned to the tried-and-true refrain, claiming that the disproportionate affect on people of color did not “reflect our values.”

Saving lives in this pandemic is job one. The NYPD uses summonses and arrests to do it.

Most people practice social distancing, with only hundreds of summonses issued over 6 weeks. But the disparity in the numbers does NOT reflect our values.

We HAVE TO do better and we WILL. pic.twitter.com/VFEFV724wU

— Mayor Bill de Blasio (@NYCMayor) May 8, 2020

Reflecting values or not, it turns out, the statistics throughout the city are even worse.

BREAKING: NYPD just released coronavirus enforcement data from March 16 to May 5.

There were 374 summonses issued, which is not many.

BUT: Of those, an astounding 304 or 81% were given to people who are black or Hispanic. pic.twitter.com/vHw0NjR0oF

— Pervaiz Shallwani (@Pervaizistan) May 8, 2020

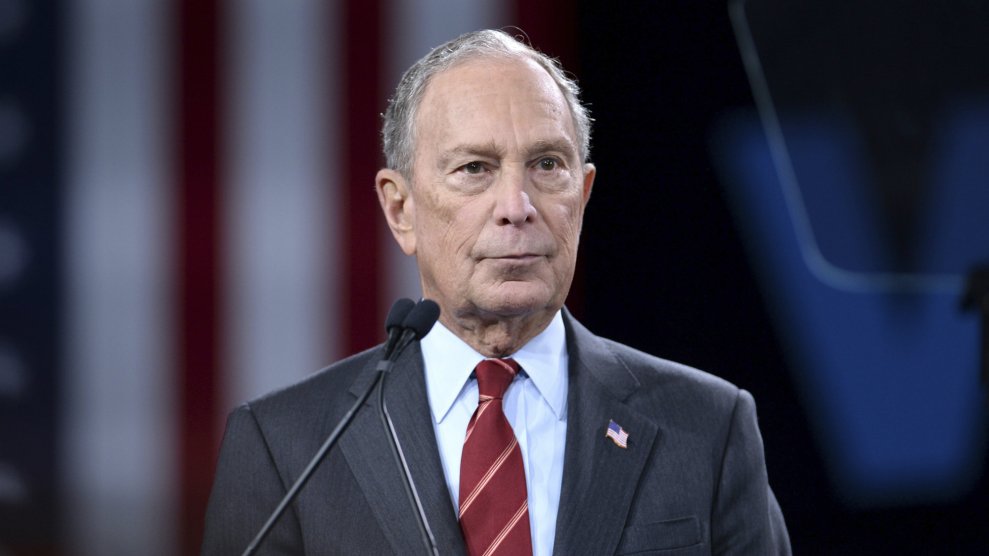

Many critics have compared the arrests to the controversial stop-and-frisk tactic, a New York Police Department policy where officers stopped, questioned, and searched people on the street which led to the disproportionate arrests of people of color there. The policy was created under former mayor Michael Bloomberg and has been frequently denounced by de Blasio. And yet, racist policing policies persist.

On Thursday, more than two months after they shot and killed Arbery, Gregory and Travis McMichael were arrested and charged with murder and aggravated assault. And these arrests took place only after a video of the shooting went viral, sparking a national outcry. The arrests never quite feel like justice because they often don’t lead to guilty convictions. After all, in the end, that’s also not who we are.